This post was written by Jenn Parent, intern at the National Museum of American History Library. Jenn is a recent graduate from Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, GA with a BS in Anthropology. She will be relocating and attending graduate school at University of Washington-Seattle for a Master’s in Library Science this September.

I spent this summer as a library intern at the National Museum of American History and I have thoroughly enjoyed my time here and learned so much! What did I get to do while I was here? Let me tell you…

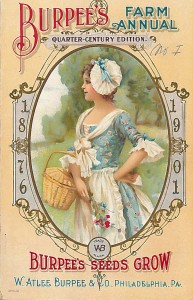

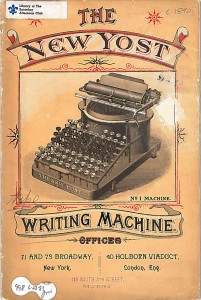

I worked on two main projects; first, the impressive trade catalog collection housed here. Approximately 500,000 pieces of trade literature are available for use by curators, researchers, fellows, or anyone who wants to take a peek. The trade lit includes sales brochures, product catalogs, price lists, company histories, correspondence, and other similar items from about 30,000 companies. My tasks varied; most often I was entering new (to us) trade lit into the system. Most of what I entered fell within the medical sciences field, but I still saw a wide variety of really nifty items, including surgical equipment from the 1800s, disposable clothing of the 1960-1970s, and smoking accessories (which included ‘water pipes’).

When I wasn’t entering trade literature, I was often pulling it to fulfill research requests. Some company collections are comprised of a single envelope, which may have anywhere from 1 piece to a dozen or so. Other collections are many, many (did I say many?) boxes (inclusive of multiple pieces) and require a whole library cart (or two or even three!) to carry them to the library for review. These items don’t leave the library so a user will review them in our reading room. When the researcher is finished, I return the trade literature to its proper location, until its next request.

Maybe trade literature doesn’t sound too thrilling to you, but I found it fascinating. To see older technology, how it was used, how it was advertised, and how it changed and affected our society intrigues me; it is a part of our collective history and as an anthropologist and a librarian/archivist-in-training that’s right up my alley!

My other project involved space – but a very specific type of space. Have you ever walked into a library and seen really full shelves with no room for another book? Did you ever think about how libraries get more shelf space? Probably not but it’s an important consideration. Space is a constant need in libraries; most do not have unlimited space and must continually make room for new materials. So how do they make room?

Libraries weed, or prune as some prefer to call it. Another term is deaccession, which sounds fancy, yeah? They all mean the same thing; as they are the terms used when librarians review and remove items based on set criteria, such as age, inactivity, damage, or relevancy. Weeding is an essential component of library collection management and is necessary for the library to remain relevant to its users and its mission.

How do we actually weed? For my project, the first step was to review 3,000 (give or take a few) titles for the letter P, which in the Library of Congress classification are books on language and literature. Criteria for my review included the item’s age, how many copies we hold, and if a free and reliable full-text version is available online. Meeting any one (or more) of these criteria makes an item eligible for removal. For example, items published pre-1923 are considered for digitization by the Libraries, depending on their condition, thereby allowing us to possibly remove the physical item to create space for new items. If an online version is available the same reasoning applies. And finally, if we have multiple copies, we may downsize to one copy, again creating room on the shelf for new materials.

After I reviewed the spreadsheet of roughly 3,000 titles, a librarian began to review my notations and make initial decisions on whether to withdraw or keep each item. If a decision is made to withdraw a title, the next step is to place the item in a holding area for the museum curators to review. Why do curators get a say? Because they use these materials to assist with research, education, and exhibits. If the curator feels the item still has research value, the item will be returned to the library shelf. If the curator approves the withdrawal, the item will be relocated to an offsite storage facility or transferred to a different Smithsonian library.

Some people may think such projects are a bit on the boring side (and yes, a full day of reviewing spreadsheets can be dry) but I have really enjoyed these projects. Why? Two reasons: one, because of the people I have met and worked with – everyone has been so welcoming, supportive, and eager to share their knowledge. I have been blessed to gain new mentors, new friends, and new experiences and skills. And two, because I’m part of the Smithsonian! It’s a thrill to be here and know in some small way I am impacting the mission of the Smithsonian: the increase and diffusion of knowledge. As a future librarian, that simple mission is also my passion. And THAT is exciting!

2 Comments

[…] https://blog.library.si.edu/2014/08/pruning-at-the-national-museum-of-american-history-library/#more- […]

Hi Jen,

Great to see you happy enjoying your journey. You are an inspiration to me and all your peers at Kennesaw State University. I wish you the best at Washington University.

Sincerely,

Toby