Blogs across the Smithsonian will give an inside look at the Institution’s archival collections and practices during a month long blogathon in celebration of October’s American Archives Month. See additional posts from our other participating blogs, as well as related events and resources, on the Smithsonian’s Archives Month website.

Although the majority of the material held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum/National Portrait Gallery Library is not unique, the library does hold a select few unique archives. The most important archival material held by the library is arguably the Random Records of a Lifetime, 1846-1931: Cullings, Largely Personal, from the Scrap Heap of Three Score Years and Ten, Devoted to Science, Literature and Art. Comprising of twenty volumes, the Random Records were collected and compiled by William Henry Holmes, the former head of Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology and the first Director of what is now known as the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

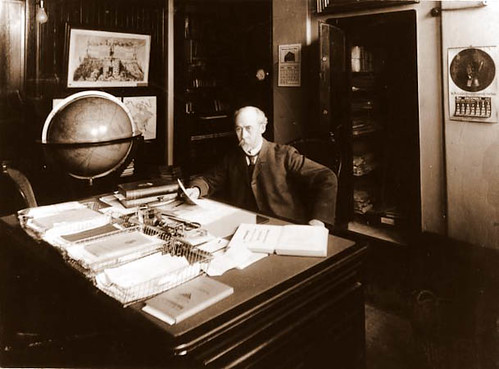

William Henry Holmes, Chief, Bureau of American Ethnology, ca. 1905. Random Records, v. 14, p. 48.

Although ultimately becoming renowned as one of the United States’ preeminent anthropologists, William Henry Holmes first sought to pursue a career as an artist. Born in 1846 near Cadiz, Ohio, Holmes was drawn to art and was primarily self taught. However, finding little support for his artistic endeavors despite multiple attempts to become a student of local respected artists, by 1871 he decided to pursue a career in education. However a tip from a local in Cadiz sent him on a detour to the Washington, D.C. studio of the artist Theodor Kaufmann who accepted him as a pupil. As luck would have it, the eldest daughter of the Smithsonian’s first secretary, Joseph Henry was also in an oil-painting class taught by Kaufmann and she suggested finding items to sketch in the collections held in the Smithsonian Castle. While sketching two birds in a display at the Castle, Holmes caught the attention of a resident ornithologist who was impressed by his work. The researcher took Holmes to the research rooms in the Castle where he met many other Smithsonian scholars. Soon the budding artist was illustrating for reports written by Fielding Bradford Meek for the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. Meek, a paleontologist and resident of the Smithsonian, mentored Holmes in both science and illustration.

The Survey of the Territories was directed by Dr. Ferdinand Hayden and in 1872 Holmes was chosen as the official artist of the Survey in the Yellowstone area of Wyoming. Holmes would spend the days sketching and exploring, and his interest in geology grew alongside his explorations of the Territories. He was appointed as an assistant geologist in 1874 and continued to illustrate for Survey reports and by 1875 was a full geologist in charge of the Survey of the San Juan region of Arizona and New Mexico. At this time he began his investigations of archaeology and anthropology and began to study the extinct cliff-dwelling Anasazi civilization. In 1880 Holmes joined the United States Geological Survey and in 1889 transferred to the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE), a research unit of the Smithsonian focusing on North American Indian cultures. Holmes eventually became the head curator of the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian United States National Museum and then chief of the BAE.

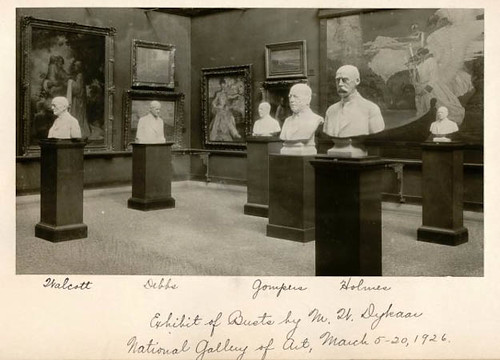

From its inception the Smithsonian Institution was authorized to collect and exhibit art. Since the Smithsonian Secretary Henry and Assistant Secretary Charles Jewett (the librarian also in charge of the art collection) believed the Smithsonian would never be able to collect great works of art (since in their mind the “great works” were all in Europe), they collected copies and casts for exhibition as well collecting prints, drawings, and paintings (especially with American Indian subjects). The art collection was placed under the auspices of the Anthropology department, one of the five major divisions of the National Museum of the Smithsonian. As a result, with Holmes as head curator of Anthropology, he oversaw the art collection. Eventually there was a movement towards the formal establishment of a National Gallery of Art for the nation and in 1906 a federal court established that the Smithsonian’s art collection a “National Gallery of Art.” Many important art collection donations followed. Holmes was appointed curator of the National Gallery and served as its curator as well as the head curator of Anthropology until 1920. In 1910, the gallery opened the first exhibits in new US National Museum building (now the Natural History Museum). In 1920 Congress granted the gallery enough funds to become a separate Smithsonian bureau and Holmes resigned his Anthropology post to become the first director of the National Gallery Art (which is now known as the Smithsonian American Art Museum). Thus Holmes came full circle back to art world and he remained director until he retired in 1932.

Exhibit of busts by Moses Dykaar, National Gallery of Art, March 5-20, 1926. Random Records v.14, p. 156.

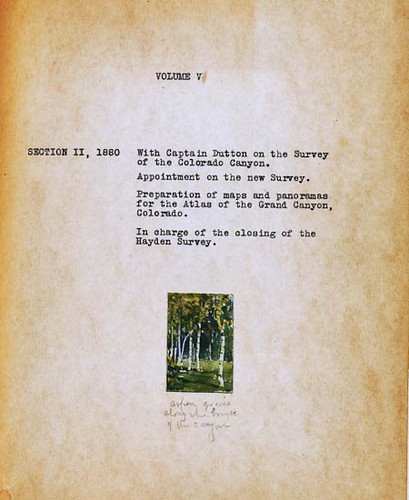

The Random Records comprise of twenty volumes of materials including newspaper clippings, personal documents, articles, photographs, correspondence, personal memoirs, anecdotes, and notes. Volumes one through sixteen of the original volumes are held in the Library of Smithsonian American Art Museum/National Portrait Gallery (microfilm copies are also held the AAPG library and the Smithsonian Archives). The last four volumes are held by Holmes’ great-granddaughter. The Library is honored to be the home of the volumes chronicling the life and career of such an important figure in the history of the Smithsonian. A truly gifted artist, scientist, researcher, and scholar, William Henry Holmes was an important figure in the Smithsonian’s anthropology department and played a key role as first the curator and subsequently first director of what would become the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Page from volume 5 of Random Records

Notes: most of the biographical information of Holmes comes directly from the Random Records.

Other resources providing supplementary information:

Fernlund, Kevin J. William Henry Holmes and the Rediscovery of the American West. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2000.

Fink, Lois Marie. A History of the Smithsonian American Art Museum: An Intersection of Art, Science, and Bureaucracy. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007.

Goetzmann, William H. “Limner of Grandeur: William Henry Holmes and the Grand Canyon.” The American West: The Magazine of Western History 15 (May/June 1978): 20-21, 61-63.

Nelson, Clifford M. “William Henry Holmes: Beginning a Career in Art and Science.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society of Washington, D.C. 50 (1980): 252-78.

— Doug Litts

Be First to Comment