Egypt, Sudan, and Jihad are much in the news today. What follows is a brief overview of some of the history behind the news. We began with “Part I: The Mahdi’s world: Social and Political Conditions”. This installment, Part II, is followed by “Part III: The Mahdi: The Rise and Fall of the Mahdist State”. This blog series was written by Judith Schaefer, volunteer in the Warren M. Robbins Library, National Museum of African Art.

PART II The Mahdi’s World: Slavery, Bedrock of Sudan’s Economy

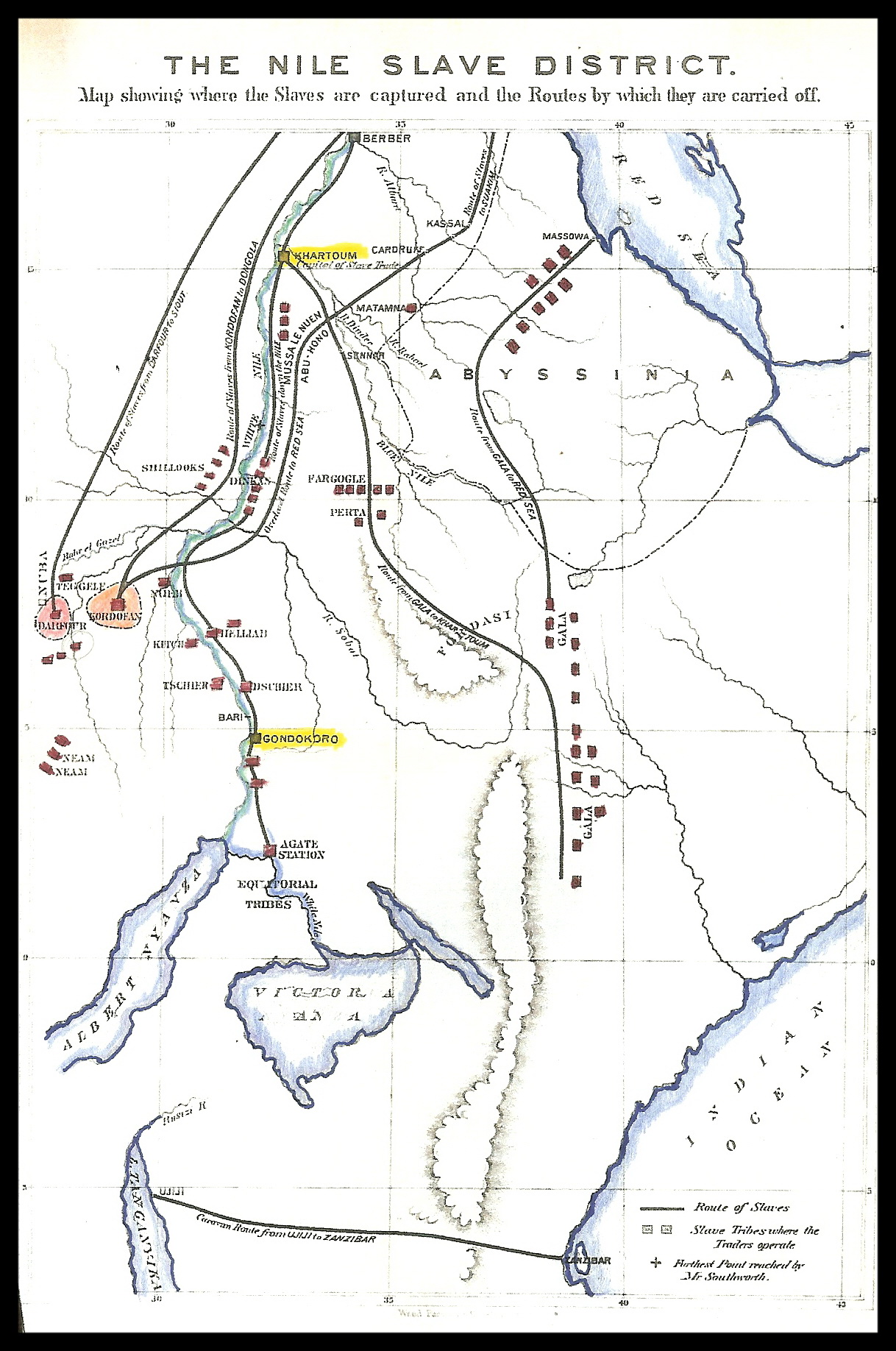

From the beginning of historic time, and undoubtedly before, there has been a trade in slaves throughout the Nile Valley spreading across the Red Sea and into the middle East. The Pharaohs, the Ptolemies, the Romans, the Arabs, and the Turks in ancient and modern times all took slaves from the greater Nile valley. . . . but it was not until the conquest of the Sudan by the forces of Muhammad Ali Pasha, the Viceroy of Egypt (1805-49) that the slave trade became an organized function of an Oriental colonial government.[1]

As we saw in Part I, under Muhammad Ali, the Caliphate monopolized the trade in ivory and slaves in Sudan. This exclusive arrangement ended in 1843, and in 1854 the government even stopped licensing traders; as a result, private traders—Europeans, Turks, Arabs—flourished. Between 1852 and 1863, for example, riverine trade on the White Nile—Khartoum to Gondokoro— increased ten-fold.

Between 1854 and 1856, the overland route into the Bahr el-Ghazal (Gazelle River) region got a huge boost from a French diplomat named Alphonse de Marzac, who decided to quit his post in Cairo for the more lucrative life of a trader. To deal with the proliferation of stations (zaribas) in that region, he invented a system to allocate power and access among the traders, which came to be known as Marzac’s Rule. After Europeans were edged out of the trade, around 1867, Arab traders continued to embrace the Rule’s efficiencies.

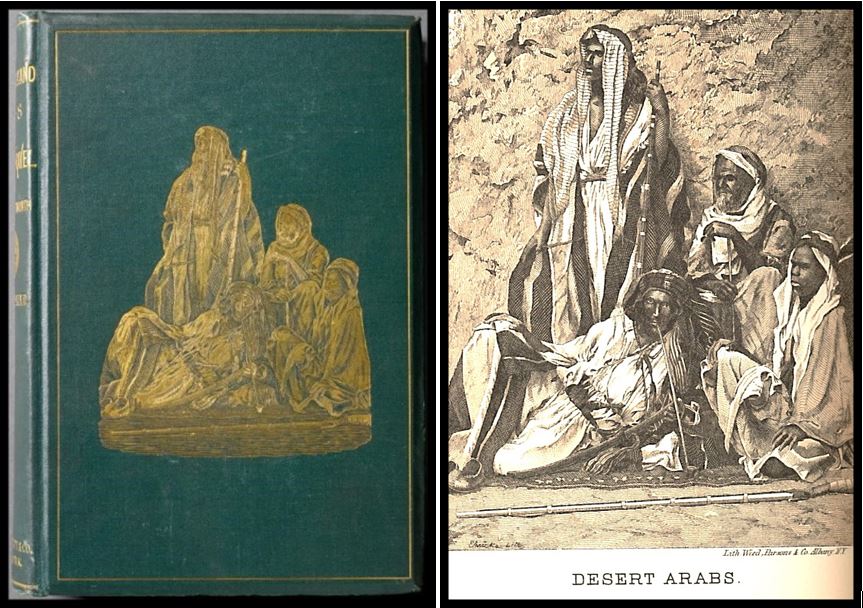

This original edition of Southworth’s Four Thousand Miles of African Travel is one of many eye-witness accounts of 19th century Africa on the shelves in the Warren M. Robbins Library, National Museum of African Art. The image on the cover (below left), embossed in gold, is adapted from the lithograph, Pl.3.,“Desert Arabs” (below right).

Southworth, intrepid reporter for the New York Herald, Secretary of the American Geographical Society, and all-around eccentric, described a slave raid:

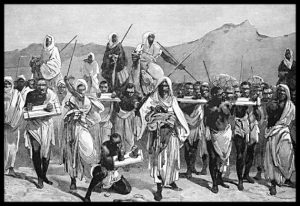

When the expedition is ready, it moves slowly to the Neam country. For example, if one tribe is hostile to another, the trader joins with the stronger and takes his compensation in slaves. Active spies are kept, in liberal pay, to inform him of the number and quality of the young children; and when the chief believes he can steal 100, he settles down to work, for that figure means $4,000. He makes a landing with his human hounds, after having reconnoitered the positions, generally in the night-time. At dawn he moves forward on the village, and the alarm is spread among the negroes, who herd together behind their aboriginal breastplates and deliver clouds of poisoned arrows. The trader opens with musketry, and then begins a general massacre of men, women and children. The settlement, surrounded by inflammable grass, is given to the flames, and the entire habitation is laid in ashes. Probably out of the wreck of 1,000 charred and slaughtered people, his reserves have caught the 100 coveted women and children, who are flying from death, in wild despair. They are yoked together by a long pole and marched off from their homes forever. One-third of them may have the small-pox, and then, with his infected cargo, he proceeds to the nearest station. Thence the negroes are clandestinely sent across the desert to Kordofan, whence they are dispersed over Lower Egypt and other markets.[2]

Nearly everyone in Sudan and Egypt, from the simplest farmer to the Khedive himself, had slaves. They served in armies, did field and house work, and were given as gifts, bribes, and payment of debts. Taxes could be paid in slaves. Women were sold as concubines and for harems. Some men were castrated to make them more suitable for positions of trust. Slaves were also exported for these purposes to huge markets in Arabia, Turkey, the Balkans, the Middle East, and India.[3] “Slaves were legally classified as livestock along with sheep, cattle, horses, and camels, or occasionally as ‘talking animals’. They were given peculiar names such as ‘Sea of Lusts’ (a woman), ‘Patience is a Blessing,’ or ‘Increase in Wealth.’”[4] Sometimes tribal chiefs would give slaves as gifts to traders, or would trade them for goods such as cowries, beads, and tin. Occasionally people would even offer themselves as slaves, to escape poverty, hunger, or violence. Slavery has a complicated history in Africa.

Today, we would call this a humanitarian crisis of epic proportion, but for Egypt and Sudan it was business as usual. (And so it was in parts of the United States from its founding until 1863.) The trade and the slave-owning way of life were sanctioned by centuries of tradition and, importantly, by Islam, the dominant religion.

The toll was catastrophic. By one estimate, for every slave who reached the Nile port of Dongola at least twelve died en route, and that was for only one of several routes. It wasn’t just the slaves who suffered; families were torn apart, villages destroyed, whole regions depopulated and laid waste, and, perhaps most pernicious of all, people came to regard their fellow humans as commodities. Southworth wrote, “If we extend the bounds of inquiry to the northern and western coasts, and wherever the sailing craft carry off their cargoes in defiance of law . . . more than 1,000,000 souls will be comprised in the number annually carried away, killed, or made broken-hearted by the slave trade.”[5]

And here’s this insight from Richard Gray (1929-2005), one of the earliest and most gifted pioneers of African history as a subject worthy of academic study, concerning this slave trade: “In due course, this created a context in which violence was established as a normal relationship between Southern Sudanese and the outside world.”[6] Contemporary events bear him out.

Under Isma’il Pasha (see Part I), the Turkiyya extended its rule far beyond the Nile Valley and, bowing to pressure from France and England, stepped up efforts to quash the slave trade. Isma’il, ever looking West, increasingly chose Europeans to enforce his unpopular policies, naming them governors (pashas) of his new provinces. Among the first was the Englishman Samuel White Baker.

Sir Samuel White Baker (1821-1893)

In 1869, Isma’il Pasha hired Sir Samuel White Baker to do the dirty work. He appointed him governor of the new Equatoria Province, a region in the uppermost reaches of the White Nile, which Baker was to claim for Egypt. He was to improve the lives of the inhabitants and stamp out the slave trade, two goals not necessarily compatible and probably unattainable. To the left is Sir Samuel in his Pasha uniform, but he was a man of many parts: civil engineer, big game hunter, explorer, military man, naturalist, writer, and abolitionist, and a man with friends in high places–in short, the quintessential Victorian hero.

This would be Baker’s second Nile journey: between 1862 and 1864, he and his wife had ascended this legendary waterway to its headwaters, discovered Lake Albert, and explored that part of central Africa. This arduous and dangerous adventure earned him a hero’s welcome at home and a knighthood; but Her Majesty’s government was not at all pleased to learn about Baker’s new mission. England was deeply interested in its Egyptian investments and the security of the Suez Canal but was opposed to military involvement in the chaotic Sudan. The Mahdist rebellion would change all that.

Lady Florence Baker (1841 – 1916)

Baker’s constant companion on all his harrowing expeditions was his beautiful wife, Florence. He claimed to have spotted her at a slave market in Vidin, Bulgaria, then part of the Ottoman Empire, while on a hunting expedition in the Balkans. (His hunting companion was the exotic Duleep Singh, last Maharajah of Sikh, but that’s another story entirely.) Slaves in the region were mostly Gypsies but included impoverished Slavic peasants and an assortment of other non-Muslims.

Lady Baker was born in Transylvania, in central Romania, to a family of Hungarian aristocrats who were massacred during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848-1849. She was sent to an orphanage but was kidnapped from it at some point and sold to an Armenian slave trader. This worthy auctioned her off to the Pasha of Vidin, but before the Pasha could claim her, she fled with Baker and never after left his side.

Baker’s contract was for four years. In December 1870, after irksome delays in Khartoum, he and Lady Baker set out in steamers for Gondokoro, a settlement on the banks of the White Nile some 750 miles to the south, with a motley army of 1,200 Sudanese and Egyptian soldiers. They arrived at their destination in mid-April 1871, nearly five months later.

It had taken two months just to negotiate the stretch through the infamous Sudd, one of the world’s largest wetlands, a wilderness of papyrus swamps and shifting channels, infested with mosquitoes and water-borne parasites, crocodiles and hippopotamuses. Floating mats of nearly impenetrable vegetation (sudd), some nearly 30 kilometers long, often blocked the way and had to be cut through, no easy task when you could not see through it or over it or around it.

And of course, day and night, the suffocating, pestilential heat. On March 22, Baker wrote, “Wind S.W.–foul. The people are all lazy and despairing. Cleared a sudd. I explored ahead in a small boat. As usual, the country is a succession of sudds and small open patches of water. The work is frightful, and great numbers of my men are laid down with fever; thus my force is physically diminished daily, while morally the men are heart-broken. Another soldier died; but there is no dry spot to bury him. We live in a world of swamp and slush.”[7]

No mention of Lady Baker except to say that she had not come down with fever. She did, however, keep meticulous daily meteorological records for the entire trip: temperature twice daily, wind speed, rainfall.

Eventually Baker was able to set up a station on the river from which he could observe and intercept all vessels sailing downstream; he suspected most would be carrying slaves, and he was right.

On May 10, 1870, after stopping a suspicious vessel, he wrote:

. . . the planks which boarded up the forecastle and the stern were broken down; and there was a mass of humanity exposed—boys, girls, and women—closely packed like herrings in a barrel, who, under fear of threats, had remained perfectly silent until thus discovered. . . .I at once ordered the vessel to be unloaded. We discovered one hundred and fifty slaves stowed away in a most inconceivably small area. The stench was horrible when they began to move. Many were in irons.[8]

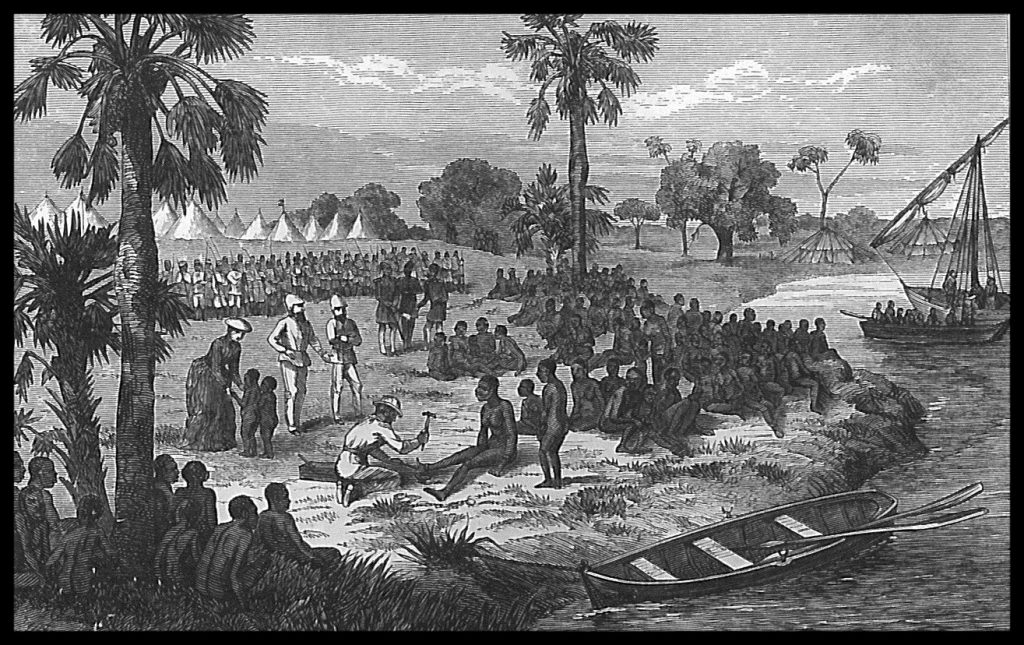

Sketches like the one above appeared in many contemporary publications. Artists made them based on detailed descriptions provided by the author whose work they were illustrating. Notice that Florence is wearing a typical Victorian dress, but the truth is that she wore the same kinds of field clothes as her husband—much more suitable for her situation, if not for Victorian sensibilities.

In addition to putting an end to the slave trade, Baker was also to open the way for legitimate trade to the Great Lakes Region, thereby fostering economic development which would improve living conditions for the local people and bring wealth to Egypt. Easier said than done. He found settlements along the river ravaged and depopulated by the plundering, murderous slave raiders. More confounding, he found that stations along the river were controlled by slave traders and that these traders were still being sanctioned by Sudanese authorities, without the Khedive’s knowledge, or so Baker claims.

Furthermore, some of those tribes whose ways of life he was hired to improve sided with the traders because the traders protected them from their tribal enemies. So Baker was often fighting traders and tribes both. Finally, even the animist blacks came to hate the government that was supposedly trying to help them because it had hired a Christian European to disrupt their intricate web of alliances and sources of wealth. Baker, evidently oblivious to these cultural issues, saw that a firm hand was clearly necessary and carried on with uncompromising zeal and sometimes brutality (he favored the lash) to enforce the abolitionist position he deeply believed in.

The Khedive was not pleased with the patchy results of Baker’s mission, an impossible one, after all, and did not renew his contract. Baker had indeed laid the groundwork for legitimate economic development, but the slave trade persisted, and by antagonizing local chiefs, tribes, traders, officials, and other vested interests, his presence had only fueled the fires of rebellion smoldering throughout the Sudan. Baker’s successor in Equatoria was Charles Gordon, who served two years, returned to England and was back again in Sudan the following year, when the Khedive named him governor-general of all of Sudan.

In the introduction to Ismailia, Baker’s trenchant observations concerning the slave trade are worth thinking about today as we try to make sense of events in South Sudan and indeed in Africa as a whole, for, in the nineteenth century and often earlier, similar conditions prevailed across the continent.

The loss of life attendant upon the capture and subsequent treatment of the slaves is frightful. The result of this forced emigration, combined with the insecurity of life and property, is the withdrawal of the population from the infested districts. The natives have the option of submission to every insult, to the violation of their women and the pillage of their crops, or they must either desert their homes and seek independence in distant districts, or they must ally themselves with their oppressors to assist in the oppression of other tribes. Thus the seeds of anarchy are sown throughout Africa, which fall among tribes naturally prone to anarchy. The result is horrible confusion—distrust on all sides—treachery, devastation, and ruin.[9]

In 1875, the Bakers’ last year in Sudan, the future Mahdi was thirty-one years old and had already attracted a large religious following. Four years later, the Khedive Isma’il was deposed. Six years later, Muhammad Ahmad would reveal his divine mission and unleash jihad.

The trade in ivory and slaves was good business, open to anyone with stamina and a tolerance for risk. A few seasons in this line of work could, it was said, set a man up for life. Before about 1860, traders included Greeks, Armenians, Turks, Frenchmen, Italians, Britons, even Americans, mostly interested in ivory, but who knows? By the 1860s, as abolitionist sentiment began to grow in the West, the foreigners gradually dropped out, leaving mostly Arabs called jellabas (people of mixed Arab and black-African heritage), who worked out of Khartoum. In 1869, Baker estimated that 15,000 men were engaged in trafficking, including governors and top Egyptian officials. A few amassed great power and wealth. The most powerful of the traders was al-Zubayr Pasha Rahma Mansur.

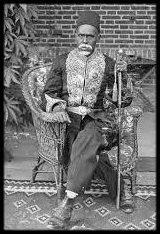

Al-Zubayr Pasha Rahma Mansur, Master Slave Trader (1831- 1913)

Al-Zubayr came from a jellaba family in Khartoum who claimed descent from one of the Prophet’s uncles and were traders by tradition. Zubayr learned to read and write Arabic and, like all students, studied the Koran and metaphysics. First, he apprenticed himself to a cousin who was a major trader with his own zariba, but after a brief learning period he decided to strike out on his own.

In 1856, he set out from Khartoum with a boat and a load of trade goods—colored beads, cowries, tin, brass wire, guns—for the Bahr al-Ghazal, the region in southwest Sudan where many Khartoum traders had already set up their “bush empires.” He located his main zariba, which came to be known as Daym al-Zubayr, astride traditional regional trade routes; it soon became a point of supply and assembly for trading parties entering and leaving the hunting grounds. In 1870, the year before Baker’s appointment, over 3000 jellabas passed through; in 1872, al-Zubayr claimed an income of 12,000 pounds a month, an annual count of tens of thousands of slaves transshipped to market, and a private army of 10,000 slaves.

Unlike many traders, Zubayr reinvested his profits in more guns and men. Eventually, after many battles and certain “understandings” with regional ethnic groups, he owned some thirty zaribas in southwest Sudan and what are today parts of Chad and the Central African Republic, an empire as large as France, where his rule was absolute. He also licensed other traders, both Arab and Egyptian, to operate within this fiefdom.

The German botanist George Schweinfurth visited Dem Zubayr in 1871. He found it to be a small town of many thousands of people, including Zubayr’s army, government officials, and traders and their armies, all with their wives, concubines, children, personal slaves and their families, plus a group of religious authorities (ulema). To survive, this parasitic community raided surrounding villages, stealing cattle and food crops and taking slaves not only for service in the zariba but also to work the traders’ own farms back in northern Sudan and, of course, to sell to foreign markets.

Schweinfurth reported seeing four classes of slaves, all subjected to “unbelievable degradation and cruelty”: adult men, who served as soldiers; boys ages seven to ten, who carried their guns and ammunition; women, “passed like dollars from hand to hand” as wives, concubines, and household servants; and both men and women to do field work and care for animals. He also reported that Zubayr’s court was “little less than princely.”

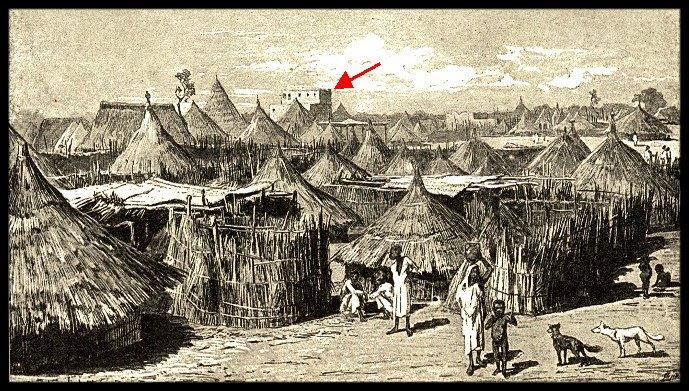

The zeriba above was built by al-Zubayr and then occupied by his son, Suleiman. Junker described it: “Around the whole zeriba runs a double and treble palisade, 26 feet high; within this enclosure the several courts are separated by matting almost hard as boards, and behind them are grouped the high and spacious dwellings surmounted by conic roofs. Suleiman’s residence, now occupied by [General Romolo] Gessi, was built in the style of a two-storeyed house [visible in the background] in Khartoum.

In 1874, Zubayr and his slave army conquered the Darfur sultanate and offered to turn it over to the Khedive in exchange for being named governor (Pasha) of Bahr-al-Ghazal. The Khedive, reluctant to so empower a slave trader, called Zubayr to Cairo, in 1876, to discuss matters, and detained him indefinitely. His twenty-two-year-old son Suleiman took over at Dehm Zubayr (renamed Dehm Suleiman). The following year, Gordon, now governor-general, intensified the government’s efforts to suppress the “ infamous commerce,” infuriating the traders, whose very way of life was at stake.

Zubayr wrote to his son urging him to free Bahr-al-Ghazal from the Egyptian troops. Thousands of traders, each with his own private army, answered Suleiman’s call, and a massive armed rebellion was underway. Gordon named an Italian general and friend from previous campaigns, Romolo Gessi, to head the Egyptian army and sent him off through the western desert to put it down. Gessi’s forces, after ferocious battles and great deprivation, succeeded. Suleiman surrendered, and Gessi had him shot—a deed that drove the traders into the arms of the Mahdist movement. Gessi set up headquarters in Dehm Suleiman and moved into Zubayr’s comfortable former house.

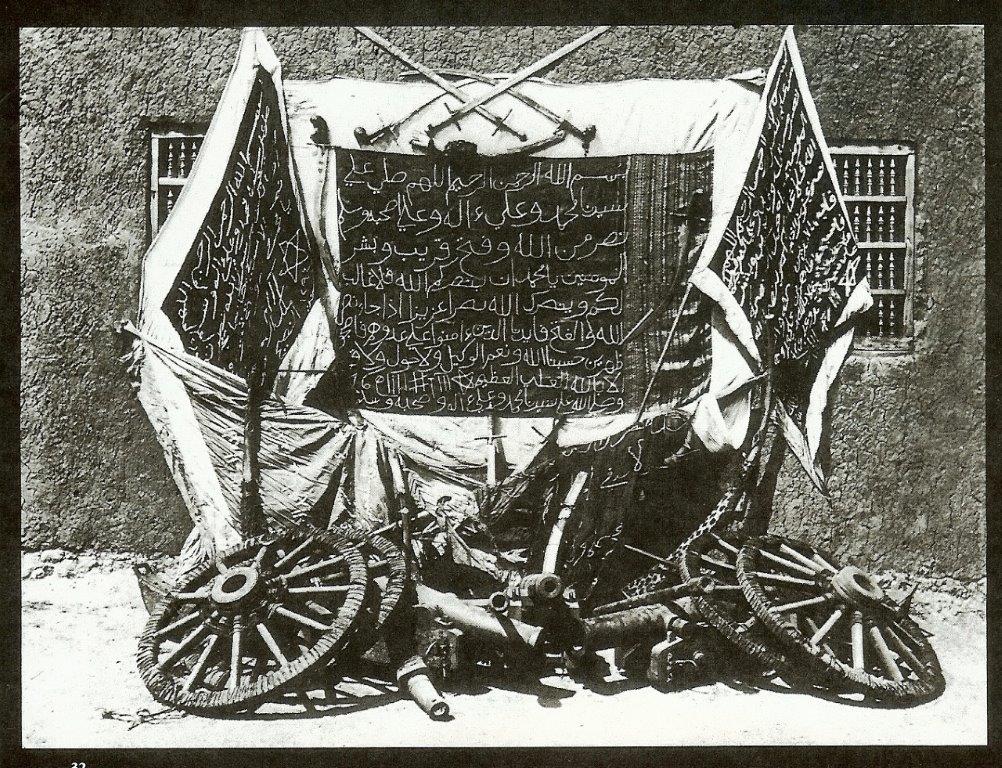

Images of arrangements of war trophies were popular in 19th century Europe. The photograph above shows not only traditional swords and black battle flags bearing religious messages but also rifles and canons that Suleiman’s army had captured from the official governor of the Bahr al-Ghazal. The black flags prefigured the Mahdist declaration of war just three years later and reflected the saying in the Hadith, “The black flags will come from the east, led by mighty men.” This photograph was taken by Richard Buchta, an Austrian photographer, happened to visit Dehm Suleiman shortly after Gessi’s victory.

Was al-Zubayr really “a quiet, far-seeing, thoughtful man of iron will—a born leader of men”? Sir Reginald Wingate, a famous British general and administrator in Sudan, thought so.[10] So did General Charles George Gordon, then governor of Sudan, who, asserting that Zubayr was the only man in the country strong enough to stave off imminent disaster at the hand of the Mahdi, proposed that Zubayr replace him. The British government rejected the idea, a decision that led inexorably to the fall of Khartoum (see Part III). In 1899, Zubayr was allowed to return to his estate north of Khartoum; he died there in 1913.

Zubayr himself wrote, “I never sent a single slave to Cairo or a single eunuch.[11] When I captured slaves, instead of selling them I formed them into an army of my own, giving them good pay and a life of adventure, which they liked. Many of these southern Sudanese are great fighters, and many of them joined me of their own free will. They would not have done that if I had not treated them well.”[12] Other accounts vigorously dispute this.

Bibliography

Collins, Robert O. “The Nilotic Slave Trade: Past and Present.” Slavery and Abolition. A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies, 13 (1), 1992.

Daly, M. W. Darfur’s Sorrow: A History of Destruction and Genocide. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Gray, Richard. “The Southern Sudan,” Journal of Contemporary History, 6 (1971), 109-110.

Holt, P. M. The Mahdist State in the Sudan, 1881-1898: A Study of its Origins, Development, and Overthrow. Nairobi, Oxford University Press, 1977. Second Edition.

Junker, Wilhelm. Travels in Africa During the Years 1879-1881. Tr. A. H. Keane. London: Chapman and Hall, 1890-92.

Lane, Paul, and Douglas Johnson. “Archaeology and History of Slavery in South Sudan in the Nineteenth Century.” Proceedings of the British Academy, 156, 509-537. http://www.SSUK.org

Lewis, Lowell N. “The Period of Muhammad Ali.” http://www.egyptianagriculture.com

Schweinfurth, Georg August. Three Years’ Travels and Adventures in the Unexplored Regions of Central Africa, from 1868-1871. Tr. Ellen E. Frewer. New York: Harper & Brothers,

Southworth, Alvan S. Four Thousand Miles of African Travel. New York: Baker, Pratt & Co.; London: Sampson, Low & Co., 1875.

Spaulding, Jay, “Slavery, Land Tenure and Social Class in the Northern Turkish Sudan.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 15:1 (1982), 1-20.

Thomas, Frederic C. Slavery and Jihad in the Sudan: A Narrative of the Slave Trade, Gordon and Mahdism and its Legacy Today. New York, IUniverse, Inc., 2009.

Willis, John Ralph. “Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume two: The Servile Estate.” Comtemporary Review, 52, 1887.

Wingate, F. R. Mahdism and the Egyptian Sudan, being an account of the rise and progress of Mahdiism, and of subsequent events in the Sudan to the present time. London: Cass, 1968. 2nd edition.

Footnotes

[1] Collins, 140-161.

[2] Southworth, 206-207.

[3] See, for example, “The face of African slavery in Qajar, Iran—in pictures,” by Denise Hassanzade Ajiri, in The Guardian, January 14, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2016/jan/14/african-slavery-in-qajar-iran-in-photos

[4] Spaulding, 12

[5] Southworth, 208.

[6] Gray, 109-110.

[7] Baker, 44.

[8] ___, 78.

[9] ___, 18-19

[10] Wingate, 109.

[11] Eunuchs were much in demand throughout the Ottoman Empire. See “Eunuch,” in Wikipedia for a historical overview of this horrific practice, especially Section 2.8 and 2.8.1., “Ottoman Empire.” . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eunuch

[12] Thomas, 34.

Be First to Comment