The first in a series of ongoing blog posts from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative, spotlighting the labor of Smithsonian media collections staff.

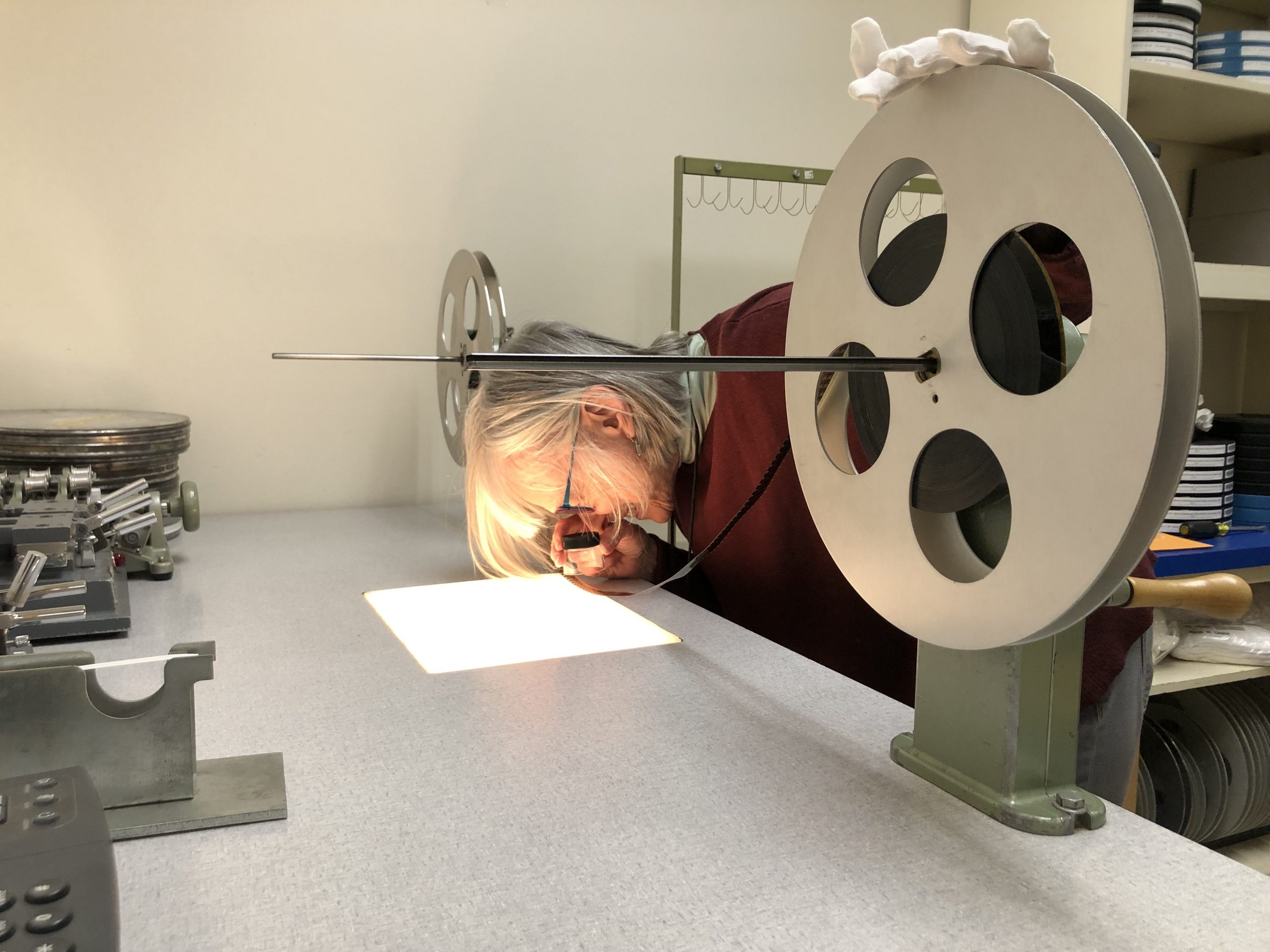

With millions of exceptional world-class collections across 21 museums and research units, it’s easy to overlook the most amazing part of the Smithsonian Institution—namely, the brilliant and dedicated staff and employees who make it all happen. Our new pan-institutional Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI) is a project with a long history of development, and one could justifiably argue that it all began back in 1976 when Pam Wintle became the first dedicated motion picture film archivist at the Institution. A true living legend, Wintle worked in the field of film preservation in Washington, D.C. since 1969 (!) and as a Film Archivist at the Smithsonian’s Human Studies Film Archive (HSFA) for 46 years (!!). While she is currently enjoying a well-deserved retirement which began this year, we couldn’t help but pull Pam back into the fold to speak about her career and her impactful work at the Institution.

Walter Forsberg: How did you first get interested in working with film collections?

Pam Wintle: My professional life has been universally magical. As a twelve-, maybe thirteen-, year old growing up in North Syracuse we went on a class field trip to George Eastman House and Museum in Rochester. I remember looking at the equipment and the photographs and being completely enchanted by them.

As I stood inside the house at a railing, looking down into Eastman’s atrium, I thought to myself: ‘I would love to live in a house like this.’ Afterwards, our class took another field trip to Albany, and I went to my first museum ever—the New York State Museum. Looking at dioramas and exhibits, again I thought: ‘Gee, I would love to work in a museum.’ I simply didn’t know these things existed. The same goes for the field of anthropology, which I didn’t know existed until I was in college. I sometimes thought I wanted to be a missionary in order to know other cultures. Putting these memories all together this morning, I had the realization that: I did it! Sure, I didn’t live at George Eastman House but, fast-forward to working at the Smithsonian as a new employee in the 1970s, and I went to a conference hosted by Kodak at the George Eastman House. As I stood in Eastman’s atrium and looked up I could almost see my twelve-year old self wishfully looking down. And, now I’m working in a museum, with cultures and collections from all over the world.’ I did it! It’s been a truly magical career.

WF: Your first job working with film was at the American Film Institute (AFI) in Washington, D.C., in an era when the AFI funded preservation activities?

PW: The AFI had an active preservation program in Washington, under Sam Kula and David Shepard. The emphasis was on 35mm nitrate feature films, hence Sam’s coining of the ‘nitrate won’t wait’ slogan. I believe I started there in 1969. I had just graduated from Ithaca College and moved to DC because I had a friend here. I saw an ad for an AFI position in the paper, and I initially interviewed with the office manager but never got a ‘call back,’ as they say. Being in the AFI offices I knew: ‘this is where I want to work.’ The walls were covered in big black and white enlarged movie stills. Growing up, my moviegoing experience consisted of Saturday matinees at the Hollywood Theatre in Mattydale, New York—which still exists. I also loved watching movies on TV, and when I saw my first foreign film in college—The Servant with Dirk Bogarde—I was totally blown away. Again, I had no idea these things existed! I just kept getting more and more sucked into the world of film, and its transformative ability to make me see things differently. It could open your mind and expand your world, and I just kept getting drawn more and more into it.

WF: So, you eventually succeeded in getting a job there?

PW: When David Shepard’s secretarial position became available and he found out that my favorite film was Bambi, that was it! He said, ‘I want her.’ David was incredible and working for him was like getting a master’s degree in film. Anything I wanted to learn, he was there ready to help me. Eventually, as most AFI activities moved to California, the preservation program and the theatre were the only things left in D.C. The preservation program offices relocated from the Kennedy Center to the Library of Congress, where the AFI collection was housed.

WF: When did you leave the AFI working with David Shepard?

PW: I guess I left the AFI around 1974, as the funding for its preservation program started to diminish. David had left prior and started working for Blackhawk Films (in Davenport, Iowa) overseeing a PBS series called Lowell Thomas Remembers—which revisited footage from Fox Movietone News collection, making a half-hour highlights TV program. I think they made programs for every year from 1916 to sometime in the 1960s. David knew I wasn’t fully-employed and asked if I would go out to Iowa and be his assistant, handling a lot of nitrate film as part of producing this TV program. That was about a five-month gig, and a wonderful experience. I edited a couple of those programs that were broadcast on PBS.

WF: I’ve heard that you also worked as a film projectionist?

PW: Well, just as a casual one for the lunchtime screenings I ran while at AFI. But I did serve as projectionist on occasion for several dignitaries. My AFI colleague met dancer Rudolf Nureyev at a reception when he was in town. Knowing that Nureyev loved film, she asked: “What film have you never seen, that we could screen for you?” He said, “Intolerance”(D.W. Griffith, 1916). So, we held a private screening for Rudolf Nureyev with (AFI film preservationist) Bob Gitt’s 16mm copy. Bob trusted me well-enough to project his personal print that had been autographed by the film’s star, Miriam Cooper. I got to meet Nureyev, who was bigger to me than any movie star, and he even handed me a rose! I said to him, “I’m so pleased to be able to project this film for you, and I know D.W. Griffith would be equally pleased.” [Laughs] That inspired an enormous smile on his face, and my projection was flawless!

At the Smithsonian, I projected several films for the Dalai Lama, but I didn’t get to meet him. This was during the E. Richard Sorensen National Anthropological Film Center days of the late-1970s, and the Dalai Lama was coming to the Smithsonian. Secretary Ripley met with him, and we screened several film compilations of Tibetan footage that I edited.

WF: You also worked at the historic Circle Theatre, correct?

PW: Yes, I did for several years, which was on Pennsylvania Avenue between 21st and 22nd Street. It was the oldest continuously-run movie theater in Washington until it was torn down, maybe 20 years ago. I sold tickets two nights a week, and it paid my grocery bills. That job really gave me an appreciation for soundtracks and sound design because I was only able to hear the films from the ticket booth, not see them. When I eventually began my position at the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Film Center, my sensitivity and awareness about the synchrony of sound and image were something that became central to the job.

WF: How did you come to start working at the Smithsonian in 1976?

PW: I first met ethnographic filmmaker John Marshall while attending something called the Summer Film Institute, held at Hampshire College and run by the University Film Study Association out of Boston. One night John, his ethnographic filmmaking colleague Timothy Asch, and I, were sitting on a balcony in Washington having drinks. The two of them were in town for an event and they started telling me about this new organization at the Smithsonian that was going to be created called, the National Anthropological Film Center [now the Human Studies Film Archive (HSFA)]. It sounded like a dream come true and exactly what I wanted to be doing. John said, ‘Well, let me write you a letter of recommendation,’ and I said, ‘OK.’ I still don’t know who he was describing in that glowing letter, [laughs] but the new Film Center’s director E. Richard Sorensen contacted me for an interview and that was it. I recall that they were interested in my AFI background as an archivist who had preservation experience. I think that was their missing piece that was needed. Rather than a filmmaker they really envisioned hiring somebody, who would look after the archival side of things that the filmmakers couldn’t or wouldn’t do.

WF: Your tenure at HSFA was so profound, but can you enumerate a few of your career highlights?

PW: Are you familiar with Henry Wilhelm? He’s an imaging conservation researcher who wrote a book on color film photography—it’s like the Bible, on the subject. Well, Henry credits us at HSFA as one of two archives in the world having the first cold storage facility for motion picture film. I can’t remember if ours predates the cold vaults at the Library Congress, but true ‘cold storage’ of (then, around 40 °F) is essential in extending the life of motion picture film. Now, we have a second, more recent sub-zero vault at the Museum Support Center in Suitland, and I consider those film storage facilities to be the second-proudest crowning achievement of my Smithsonian career.

WF: And the proudest one?

PW: That would be working to have the John Marshall Ju/’hoansi (Bushman) film and video collection (1950-2000), documenting the Ju/’hoansi people of Kalahari Desert in northeastern Namibia, inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Registry. I say that not because I did it alone, but because I was very much the driving force. We were only the third audiovisual collection be added to the Registry. It was an enormous, difficult, and laborious effort, but something really international and not just American-centric. This is a collection for the world, and the UNESCO’s interest in highlighting indigenous communities made the work to have the collection added to the Registry extremely gratifying. Karma Foley, and Jake Homiak, Daisy Njoku, and Richard Kurin were all Smithsonian collaborators that were also really invested in this effort.

WF: In the course of your career, you’ve mentored so many professionals now working in the audiovisual preservation field. Many of them have since become directors of their own institutional archives. Do you have any words of advice to young folks out there who are interested in getting started ‘in the biz’?

PW: Be curious, and be open because one never knows the shape of possibilities. And a good mentor is priceless. I had them as my good fortune and I love mentoring in return. I’d like to think I’ve been a decent one, at least! [Laughs]

2 Comments

Nice post.

Pam is the very best mentor. For my generation she helped inspire, launch and sustain new archives. She’s a stalwart friend who’s been at it through thick and thin.

Walter, this is a great interview bringing Pam’s personality and achievements forward. Appreciate the pictures and their credits, too.