This post was written by Vanessa Haight Smith, head of Preservation Services.

When repairing older books, the Smithsonian Libraries conservators occasionally uncover evidence of recycling by the original bookbinders. Paper from damaged and discarded volumes was frequently used when binding new books. Why use a new, clean sheet of paper when a leftover scrap would work just as well?

With the development of moveable type in the mid fifteenth century, numerous manuscripts were replaced with printed copies and eventually, the discarded parchment became useful material for new bookbindings. While the use of binding waste has varied throughout the centuries (having been used on all parts of books from covering material to paper repair) we most frequently see it used to line spines.

(Raisons des Forces mouvantes . . .1615, Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum Library)

These paper linings were applied to the spine once the textblock was sewn. By the nineteenth century, most binding waste included parts of newspapers, catalogs, and magazines – unfortunately made from acidic paper – creating staining and damage in some cases. The practice of lining spines has been replaced today with conservation-grade Japanese and archival papers.

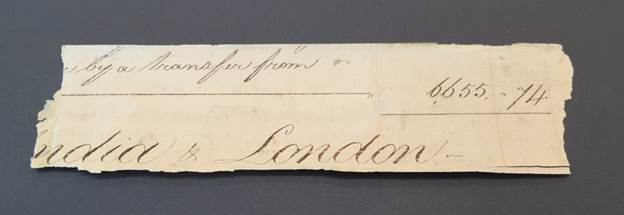

Waste used as spine linings is only visible when books are damaged in a way that exposes what lies underneath the covering. These scraps can provide interesting clues to provenance, location, and dates.

(The Naturalist in British Columbia, Vol 2, 1866, National Museum of Natural History Library)

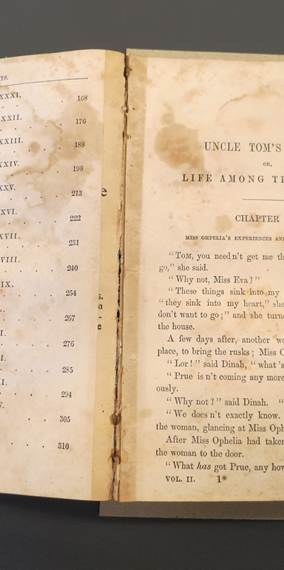

Recently, we discovered evidence of paper repair through the use of printed waste paper to guard sections of a book of an 1852 edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Visible at the gutter after the sewing failed, the sections were mended at the fold before a previous rebinding.

Be First to Comment