This post was written by Katie Boodle, Book Conservation Lab intern.

This post was written by Katie Boodle, Book Conservation Lab intern.

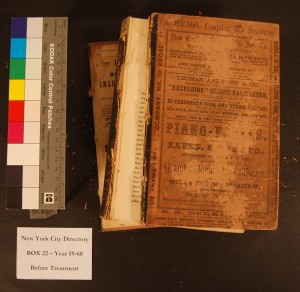

As part of the Smithsonian Libraries’ Conservation of Library Materials Internship, I had the opportunity to work on projects that addressed common conservation problems in archives and special collections: preparing works for digitization and creation of enclosures. Conservation in general is focused primarily on the stabilization of ethnographic, historical, and/or artistic objects for future or continued use. A lot of our treatment decisions, therefore, are made based on how the object will be used in the future, as well as how the objects were used in the past and the specific type of damage done to them. The main project that I worked on during my six weeks was the stabilization of a set of Trow’s New York City Business Directories dating from 1858-1867 located in the collection of Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum Library. The main purpose of repair was to prepare the volumes for digitization.

Now you may think that this is a bit strange or ask why bother stabilizing a book if it is just going to be scanned and the digital copy will be available for access online or through a database? The answer is that the volumes can’t be scanned until the digitization team can actually access and photograph the entirety of the work, which only occurs if the book is stable and functioning properly. For the Trow Directories, two of the main issues were that each volume had multiple text block breaks and detached boards. This type of damage is quite common and usually caused by the volumes being opened and closed repeatedly in the same spots while the public and researchers used them. The text block breaks and detached boards not only make it difficult to handle and photograph the volume, but can also lead to missing information.

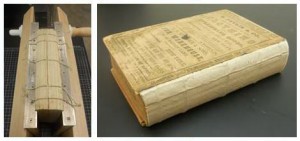

Because disbinding and completely resewing a book is a very time consuming process, for the overall stability of the rest of the binding, and the future use of the books, the volume’s loose sections were sewn locally just above and below where the breaks occurred. The local sewing anchored the loose sections and helped realign the text blocks back together. The volumes were then given a new spine lining of Aero linen which was able to be inserted into the boards and allowed them to be reattached. Both of these treatments make it possible for the volumes to then be photographed in the digitization cradle.

Making the enclosures was a bit different as it didn’t focus on treating object, but rather protecting them from further harm. This sort of treatment is common in conservation as it allows us to create a better environment for objects that are not considered to be rare—and thus tend to not be high on the priority list—without spending a significant amount of time stabilizing them. An added bonus is that it usually means that we can also deal with a number of books at once as we spend less time focusing on an individual volume.

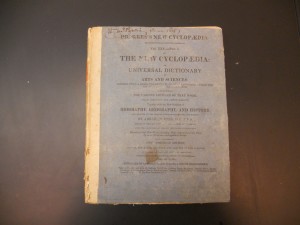

There were two main types of enclosures made. One was a modified four-flap folder that had a window cut into it so the spines of the volumes were visible. The concept for these was inspired by similar enclosures used at the Folger Shakespeare Library. These protective cases were placed on a set of encyclopedias from the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology: The cyclopaedia: or, Universal dictionary of arts and sciences and literature… First American edition by Abraham Rees from 1806-1824.

These books were of particular interest as the pages of the volumes had not been cut and their bindings were simplistic. This gives us a better idea of what sections of the volumes were used, as well as the mindset of the previous owner of the volumes. Because the pages weren’t cut and most of the books were stable enough for low level handling, the choice was made to not repair the volumes in anyway. The clear windows in the enclosures act as a security measure and also allow readers just glancing at the shelves a better idea of the type of volume inside, as you can see here.

These books were of particular interest as the pages of the volumes had not been cut and their bindings were simplistic. This gives us a better idea of what sections of the volumes were used, as well as the mindset of the previous owner of the volumes. Because the pages weren’t cut and most of the books were stable enough for low level handling, the choice was made to not repair the volumes in anyway. The clear windows in the enclosures act as a security measure and also allow readers just glancing at the shelves a better idea of the type of volume inside, as you can see here.

The other enclosure was a set of modified clam-shell boxes for a set of rare book miniatures also from the Cooper-Hewitt Library. The books were quite small and would be easily damaged as they had in some small part from previous slipcases tied together with them. To prevent further damage, a series of larger clam-shell boxes (9” x 6”, the size of an octavo volume) were created. The inner tray of the clam-shell was then built up around the volume to stop it from sliding around in the larger box. For the volumes that had broken slip cases, a second level was created to make a sliding folder that held the broken pieces in place. Many of these volumes were repaired in some capacity as the type of damage (mostly tears and areas of loss) ran the risk of causing more damage to the volume in the future.

Overall, I feel that this internship has given me the opportunity to continue honing many of the skills that I already have while also giving me practice in time management and decision making for a batch of similar objects. The internship provided a good transition from the world of academia to the workforce and having the opportunity to work at the Smithsonian, even for such a short time, has been a life-changing experience for me.

Be First to Comment