The Smithsonian Field Book Project is showcasing Frederick William True in February. This post is part of a series of blogs and social media content from the Biodiversity Heritage Library, Pyenson Lab, Smithsonian Transcription Center,and Smithsonian Institution Archives, celebrating #FWTrueLove.The campaign will include a fascinating new transcription project and exciting behind-the-scenes opportunities! Learn more on the Field Books Project blog.

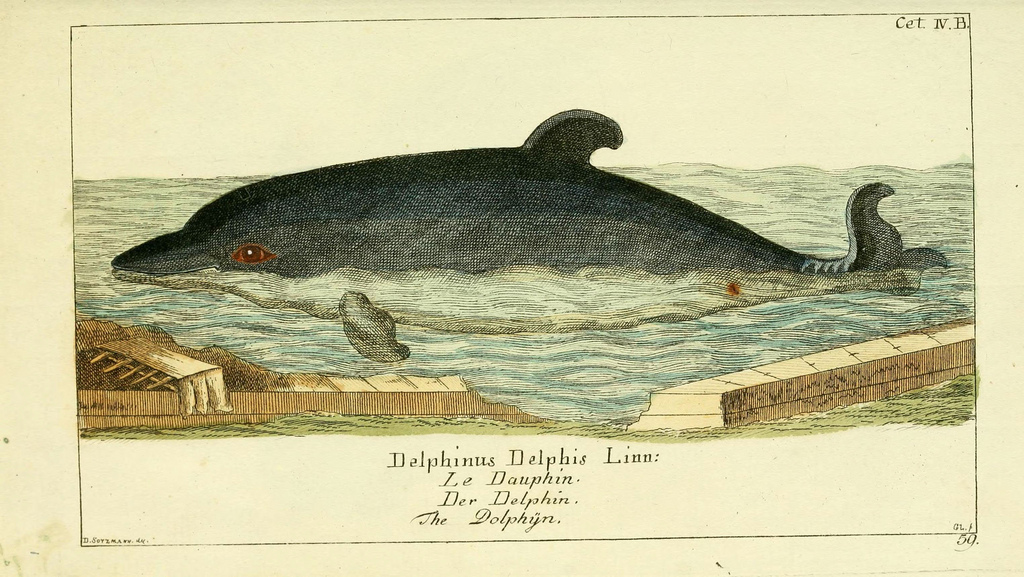

Berlin ;bei Gottlieb August Lange,1780-1789.

http://biodiversitylibrary.org/item/89995

The quest to understand and organize oceanic dolphins (the family Delphinidae) is one that requires patience and the continual acquisition of knowledge and data. This has been the reality since scientists first attempted to classify these marine mammals, and one poignantly felt by one of the world’s foremost cetacean authorities at the turn of the century: Frederick William True.

Frederick W. True (1858-1914) began his career as a clerk at the U.S. Fish Commission in 1878. In 1881, he was hired by S.F. Baird as Librarian and Acting Curator of Mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, after which he was promoted to Head Curator of Biology in 1897 – a position he held until 1911 when he became the Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. With a focus on living and marine fossil mammals, True was the first marine mammals curator at the Smithsonian. Though he is most famous for his work on the mysticetes and beaked whales, True also provided invaluable contributions to the study of the Delphinidae family.

http://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_sic_10333

True recognized that scientists at the time used non-uniform criteria to describe and classify species. Some based descriptions on external characteristics, while other relied on osteological examinations, resulting in, as True put it, two series of species. Varied criteria employment also resulted in drastically different classification schemes, resulting in a plethora of competing taxonomic trees for both Delphinidae and related families.

A preponderance of oceanic dolphin scientific names and uncertainty of species relationships was a major impediment to the advancement of Delphinidae research. Near the end of the nineteenth century, True set out to bring order to the chaos.

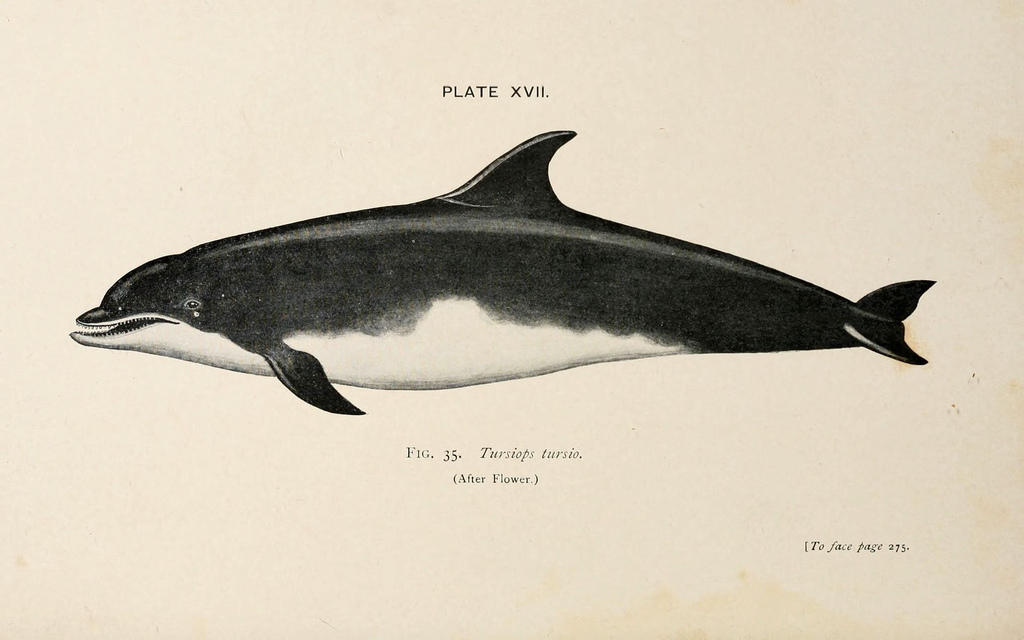

http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/1398413.

True began his endeavor with a focus on the species found off the North American coasts, but the state of affairs compelled him to expand his scope to the entire Delphinidae family. Though his work was largely based on that of Gray, Flower, Stejneger and Baird, True was the first person to attempt to analyze all available data, harmonize the many synonyms, and produce a classified list of truly distinct Delphinidae species.

True quickly realized that “a proper comparison of the species described respectively by European and American naturalists could not be made without an examination of the types.” Thus, in the winter of 1883-84, True spent four months in the museums of England and Europe studying the type specimens of the described Delphinidae species. The result of his labor was the publication Contributions to the natural history of the cetaceans. A review of the family Delphinidae, which presented a revised Delphinidae classification.

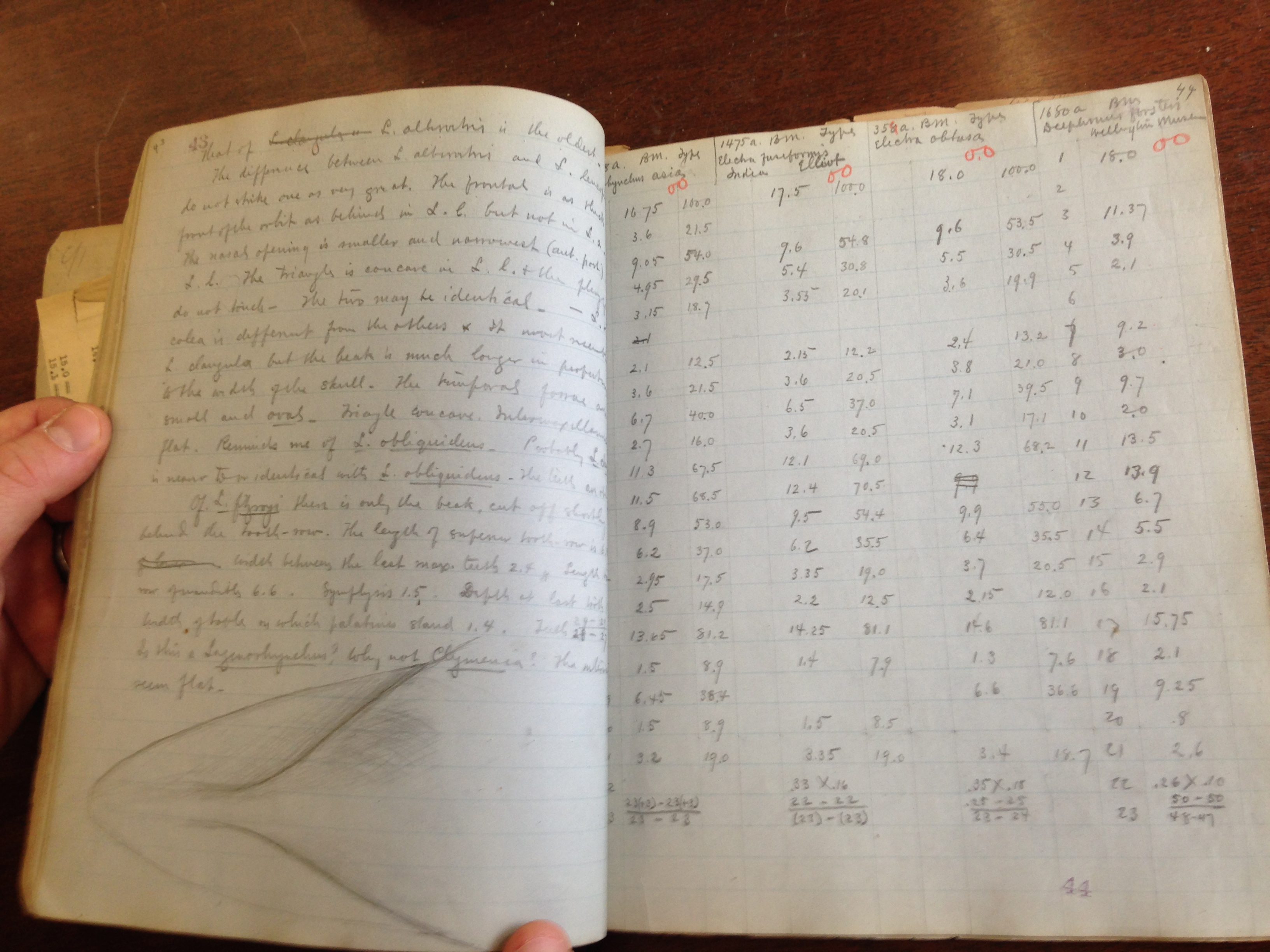

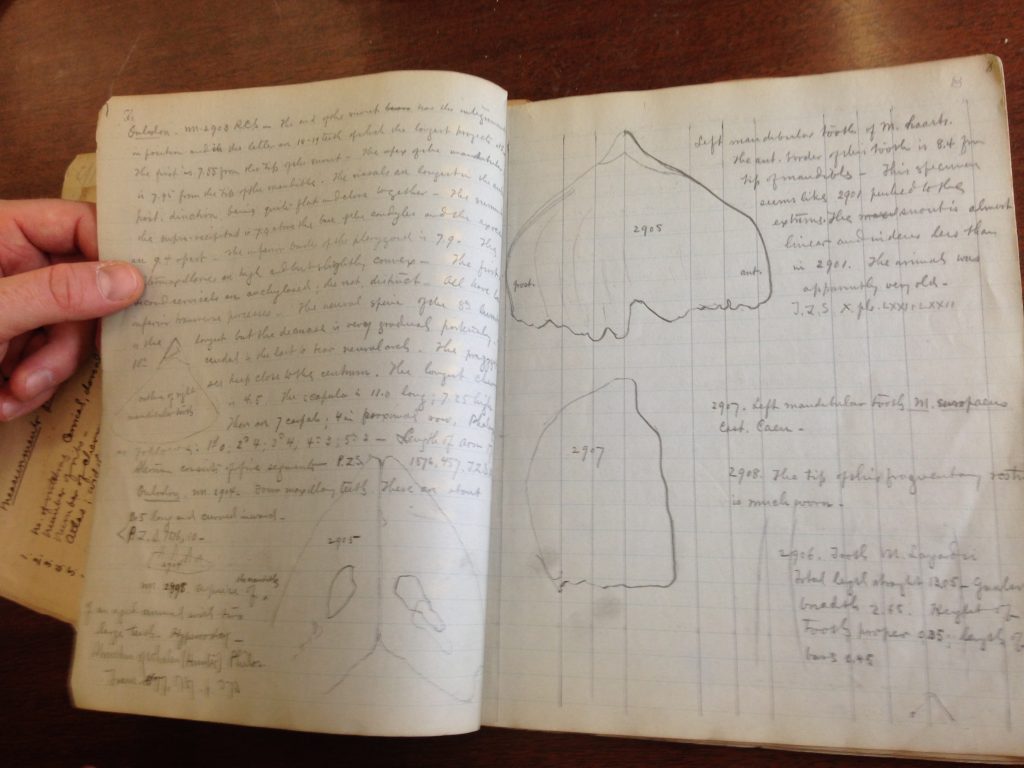

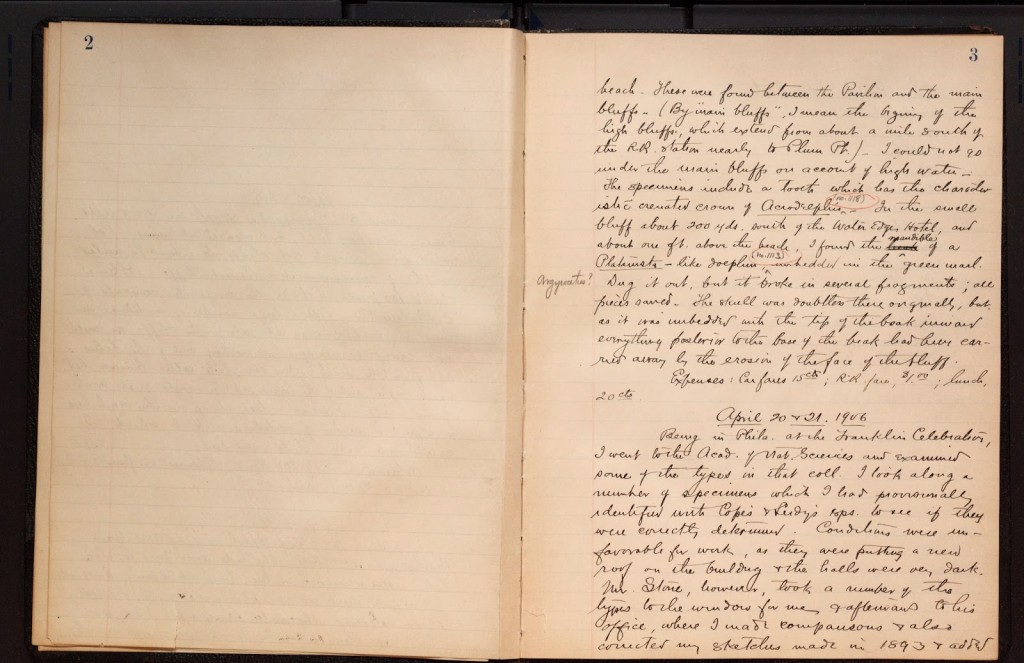

During his time abroad, True kept a journal recording the observations, measurements and data he gathered. These records were used to inform the aforementioned publication. Dr. Nick Pyenson, current Curator of Fossil Marine Mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, recently discovered this journal amongst a box of True’s manuscripts and research materials in the Smithsonian’s Remington Kellogg Library of Marine Mammalogy.

As the journal (1883-84) shows, True carefully examined and measured all of the type specimens he could find, including specimen catalog numbers, locality, sex and age if known, various lengths including total, length of beak, and girth, and other data such as the number of teeth. These kinds of data remain relevant today, where the consistent collection and curation of this irreplaceable data provides the basis for answering many different ecological, evolutionary and conservation research questions.

Even more interesting, the logbook is annotated by Remington Kellogg, the aforementioned library’s namesake and himself an authority on cetaceans. Though his time at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History postdated True’s lifetime, Kellogg took a keen interest in True’s work and annotated many of his manuscripts, including not only this journal but also True’s fieldbook of collecting trips in 1906-08.

Of course, the science of taxonomy is not a static endeavor. And indeed, new information has come to light since True revised the Delphinidae family over 100 years ago. While the total number of species, genera, and subfamilies differ depending on the classification schema used, of the 62 distinct species that True recognized, 38 are recognized as distinct today (though some under different names), and 32 are still included in the Delphinidae family. Twenty-four of the species True classified as distinct are now considered representatives of other species cataloged in his publication or are not recognized as distinct species today (i.e. nomen dubium). While many of the binomials employed by True are today considered invalid synonyms (though some have changed only slightly in spelling), 15 of the names included by True are still considered valid.

The efficiency of scientific research depends on access to raw data, specimens, and previously published information. During True’s lifetime, access to this information was especially difficult, resulting in the proliferation of competing taxonomies. Satisfying information needs often required expensive trips across oceans and countries to consult dispersed institutional collections.

Today, open access digitization initiatives are working to provide global, online access to the information required to study, describe, and classify life. The digitization of museum specimens, scientist’s raw data contained in unpublished fieldbooks, and centuries’ worth of published natural history literature allows researchers to draw connections among all of this information, see the work upon which current systems are based, compare notes across disciplines and time, and more easily harmonize synonyms and create classifications. The Biodiversity Heritage Library and The Field Book Project, through the digitization of natural history fieldbooks and publications, are two programs amidst a growing cadre of initiatives dedicated to facilitating discovery of the natural world. Through continued collaboration and a commitment to open access, we can improve the efficiency of scientific research across the globe.

This post was written by Grace Costantino, Outreach and Communication Manager, Biodiversity Heritage Library

With contributions by: Dr. Nick Pyenson , Curator of Fossil Marine Mammals, NMNH

For more #FWTrueLove, be sure to check out the Field Books Project and follow along on social media!

Be First to Comment