James Smithson, whose bequest led to the establishment in the mid-19th century of the American institution that now bears his name, famously stated in his will that funds should be used for the “increase and diffusion of knowledge among men.” This seemingly vague request is rooted in Enlightenment philosophy, the desire to create order and understanding in the world. As Heather Ewing wrote in The lost world of James Smithson, he was a member “of this distinct breed of English Enlightenment gentleman: citizens of a new republic of science, dedicated to the cause of ‘improvement.’”

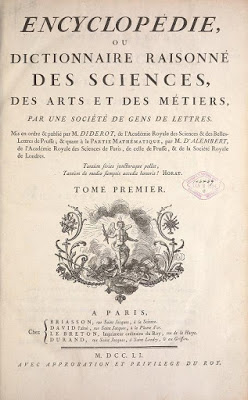

The Enlightenment era’s embrace of “the increase and diffusion of knowledge,” an attitude that so inspired Smithson, is exemplified by the monumental twenty-eight-volume publication of Encyclopédie, ou, Dictionnaire raisonné (1751-1772). It is a work which the well-traveled and learned Smithson undoubtedly knew well and in light of Bastille Day (July 14th) it seems appropriate to highlight this impressive French tome.

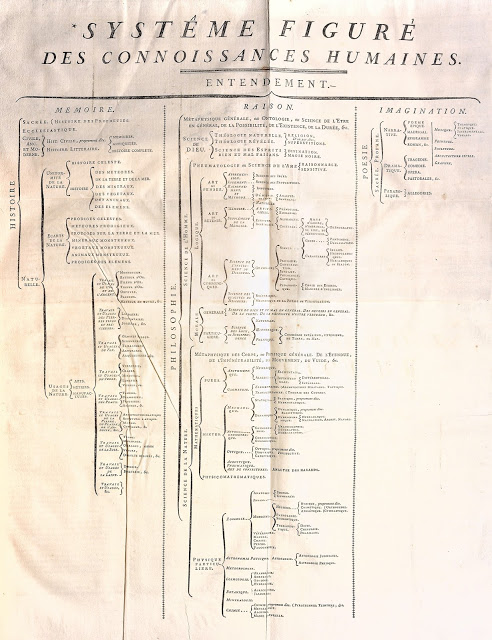

The first volume of the Encyclopédie contains the famous “Preliminary Discourse” where it is argued that all human knowledge resides in three branches: Memory, Reason, Imagination. The rationalist, secular outlook made its creators subject to censorship, official condemnation and threats of imprisonment.

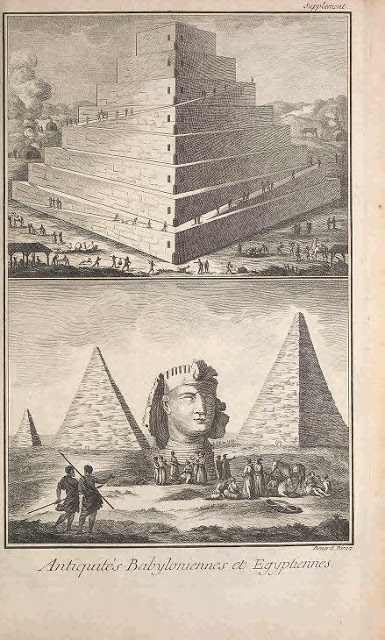

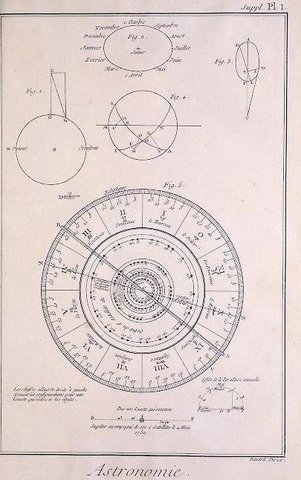

The Encyclopédie, ou, Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de Gens de Lettres (Encyclopedia, or, Rational Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts and Trades, by a Society of Men of Letters) is a reference work that was conceived with the belief that everything in the world could be explained by rational investigation. Much as the Smithsonian Institution does today, the range of subjects covered was enormous: there were not only abstract disciplines, such as natural philosophy and mathematics, but also practical sciences (mechanics, technology, medicine) and the techniques of the arts, crafts and trades.

The large-format volumes, comprised of folio pages of text printed in double columns and with the famous plates of illustrations, has a long publishing history. It all began simply as a French translation of Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia, or, Universal dictionary of art and sciences, a two-volume work published in London in 1728. But the concept for the project grew with the prospectus stating that there would be eight volumes of text and two of plates of illustrations. The general editor was the novelist, playwright and literary and art critic, Denis Diderot (1713-1784), with assistance from Jean Le Rond d’Alembert (1717-1783), another philosophe, who was responsible for mathematics and science, with a second mathematician, Abbé Jean Paul de Gua de Malves, helping out.

The Encyclopédie differed from its seventeenth- and eighteenth-century predecessors by emphasizing the arts and trades and by drawing on a wide variety of prominent contributors to record the sum of human knowledge. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Montesquieu and Voltaire were some of those prominent writers involved. It was published during a time when there was a great increase in literacy and the attending explosion in the availability of printed materials.

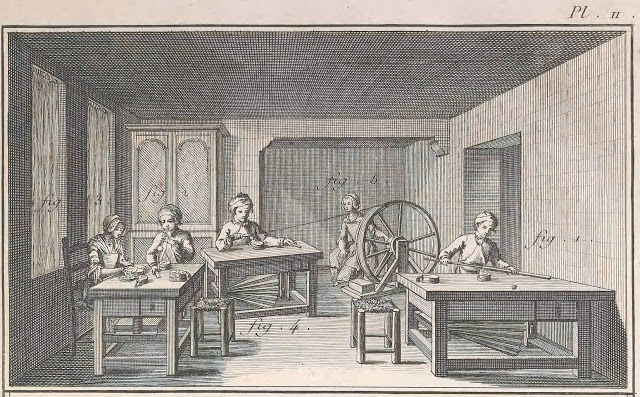

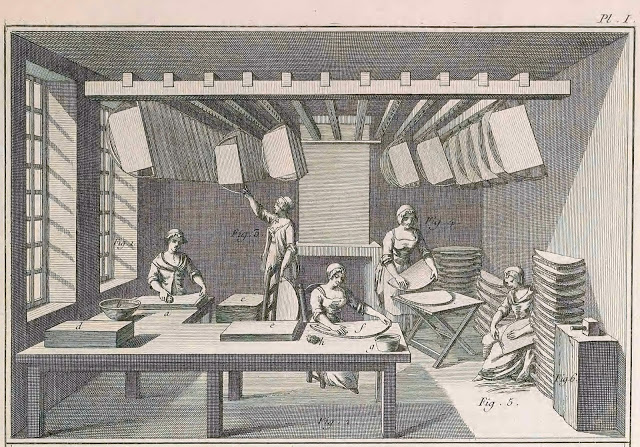

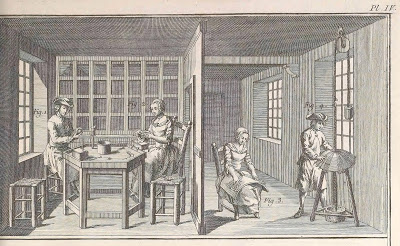

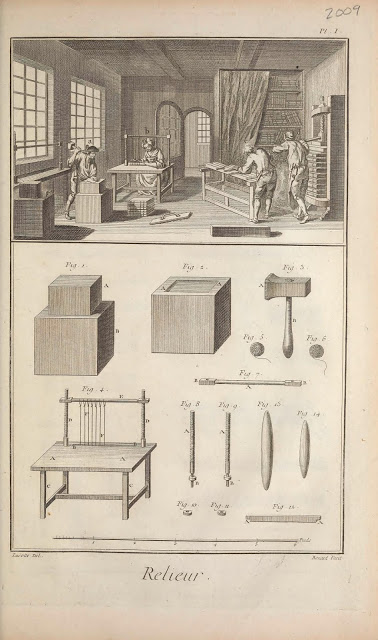

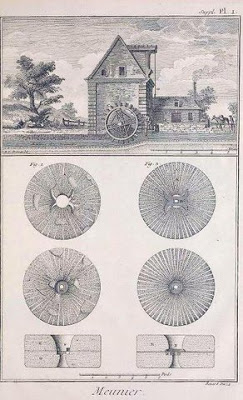

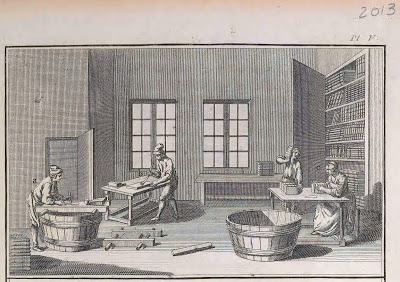

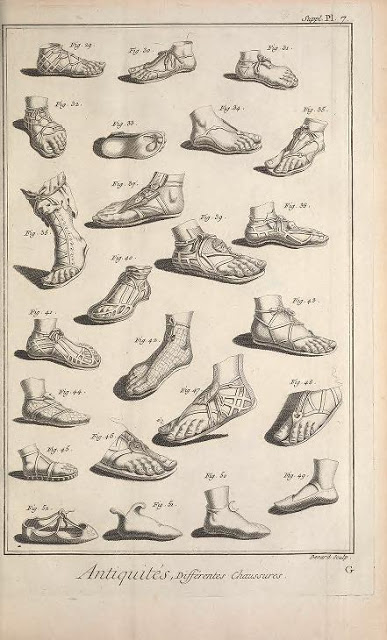

It was also a time when the guilds still closely protected their skills and knowledge, with master craftsmen teaching only by the apprenticeship system. The “métiers” of the title was not incidental: Diderot, son of a cutler, sought to reveal mechanical secrets in the hope that “our descendants, by becoming better instructed, may as consequence by more virtuous and happy.” Although the intricate details in the depictions of machines, tools, and instruments were engraved by a group of highly skilled craftsmen, Diderot himself gathered much of the information from hours of observation.

The 3,129 large illustrations are immediately recognizable from countless reproductions. The calm scenes of small workshops of the pre-Industrial-Revolution era show men, women and children employing techniques that had previously been regarded as trade secrets. The clear diagrams and drawings of artisanship and mechanics are absorbing in their detail. Even if the view of industry is rather archaic, the volumes of plates may be the most revolutionary elements of the work, providing visual examples of the philosophe principle that rational knowledge, in the portrayal of human activity, could be the basis for a new world view where happiness is tied to progress and prosperity.

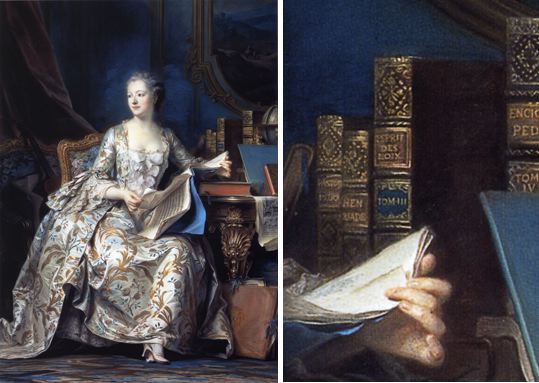

This radical world view challenged both the church and state, particularly in the earlier volumes addressing religion and politics. Although royal permission for publication had been granted, in 1752 Louis XV’s conseil d’etat threatened the editors with imprisonment. But the Encyclopédie continued to be produced because the project had friends in high places, including the royal mistress, Madame de Pompadour. Printing preceded slowly (volume three appeared in 1753). In 1759, during a difficult and unsettled period in French history, the Encyclopédie was included in an official list of condemned books and censorship forced a temporary suspension of publication. Editors defied the authorities by releasing the next ten volumes simultaneously in 1765 under that convenient and common false imprint of the time–the Swiss city of Neuchâtel.

Then, as now, scandal and controversy were good for business and the print run was expanded from 1,625 to 4,225. Also helping sales was a 1756 portrait of Madame de Pompadour, by Quentin de la Tour, shows her posing with a volume of the encyclopedia. Reprint and pirated editions of the Encyclopédie appeared, as well as foreign language imprints, even as Diderot’s originals were being released. During the American Revolutionary War, Thomas Jefferson ordered a pirated Italian edition from the Virginia Gazette. In Geneva, a folio reprint was issued between 1771 and 1776. Several less expensive versions, in the smaller quarto and octavo formats, added most to the publishing competition before the close of the century.

However radical, the Encyclopédie was not a call for revolution in mid-eighteenth-century France. An encyclopedia of this scale was expensive to produce and purchase. The intended market may have been wider but still its audience was the wealthy, educated gentlemen who would have been conversant in history, philosophy, literature, science, technology, and the arts. Purchasers of the work included the nobility, military officers, clergy, parliamentary officials, and law professionals.

The Encyclopédie’s value as a source of information on eighteenth-century industry and life is tremendous and continues to feed modern scholarly research. A quick search of the Smithsonian’s online catalog, the Collections Search Center, turns up such titles as Diderot and Goethe: a study in science and humanism, by Gerhard M. Vasco (1978); The spectator and the landscape in the art criticism of Diderot and his contemporaries, by Ian Lochhead (1982); Three early French essays on paper marbling, 1642-1765, with an introduction and thirteen original marbled samples by Richard J. Wolfe (1987); and L’Encyclopédie Diderot & d’Alembert: Les métiers du livre, by P. M. Grinevald et C. Paput (1994); Diderot et le portrait, by Jeannette Geffriaud Rosso (1998); and Robert Darnton’s Censors at work: how states shaped literature (2014).

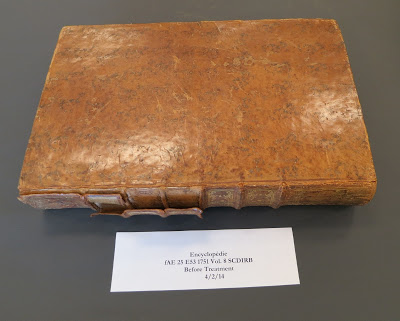

James Smithson very likely would be pleased by recent actions with one of the Institution’s editions of the Encyclopédie. As a further aid to scholarship, with open access to all, the copy in the Dibner Library has recently been digitized and placed online by the Smithsonian Libraries. To safe-guard the actual volumes for future use, this set of the Encyclopédie, ou, Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers is now being conserved by experts in the Smithsonian Libraries lab.

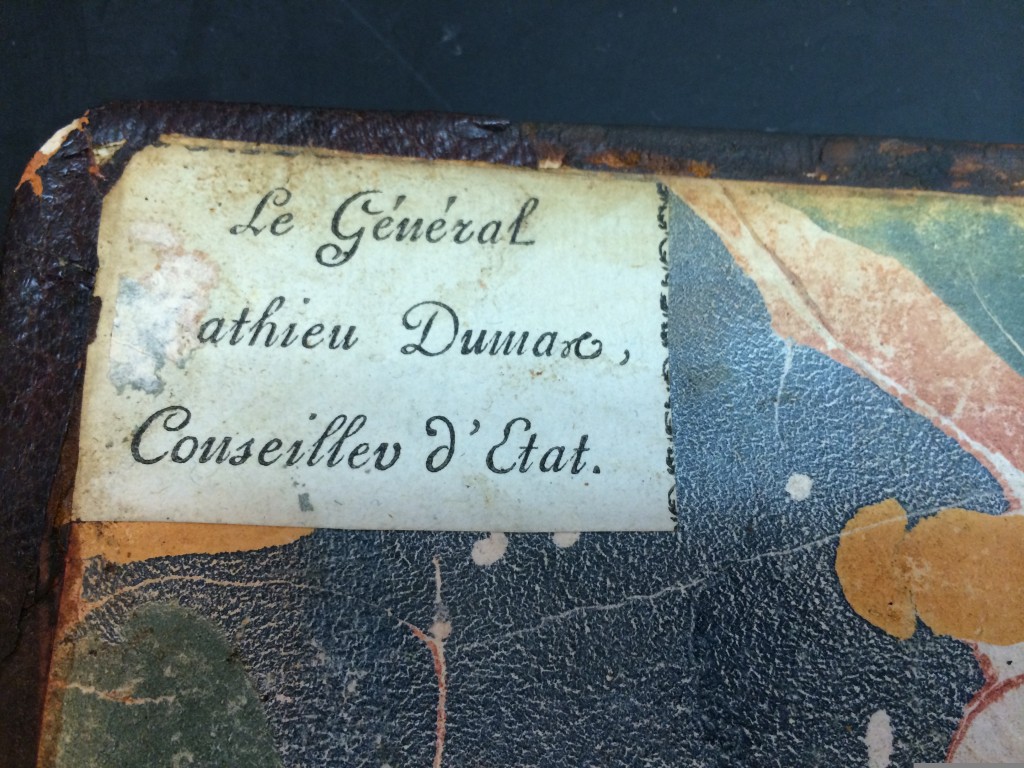

The Cooper Hewitt Library’s copy has the book label of Mathieu Dumas (1753-1837). A military officer and learned author (Précis des événements militaires de 1799 à 1807), Dumas can be seen as a typical owner of Diderot’s publication. He served as aide-de-camp to Rochambeau during the American Revolutionary War and, at the beginning of the French Revolution, he worked with Lafayette and the National Constituent Assembly. Dumas survived much during this particularly tumultuous period in French history, eventually becoming a councilor of state in 1805, and after another return to favor, resumed the position in 1818.

One Comment

Things are evolving too as of the french language … it is said that by 2050, 700 millions people will spake french on the face of the earth, of whom 80 % will be in Africa.