Written by Jessica Masinter. She is a summer intern in the Cooper Hewitt Library and a literary studies major at Middlebury College.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Indian textiles were the height of quality. Their exotic patterns, brilliant colors and dye fastness drove customer appeal among the English bourgeoisie to the point where India was considered by some to be the industrial workshop of the world. British textile manufacturers desperately tried to produce fabrics and patterns that imitated Indian textiles, attempting to ‘cash in’ on the in-demand designs. To do so, however, the British manufacturers required an in-depth knowledge of Indian textiles—and J. Forbes Watson was just the man to help.

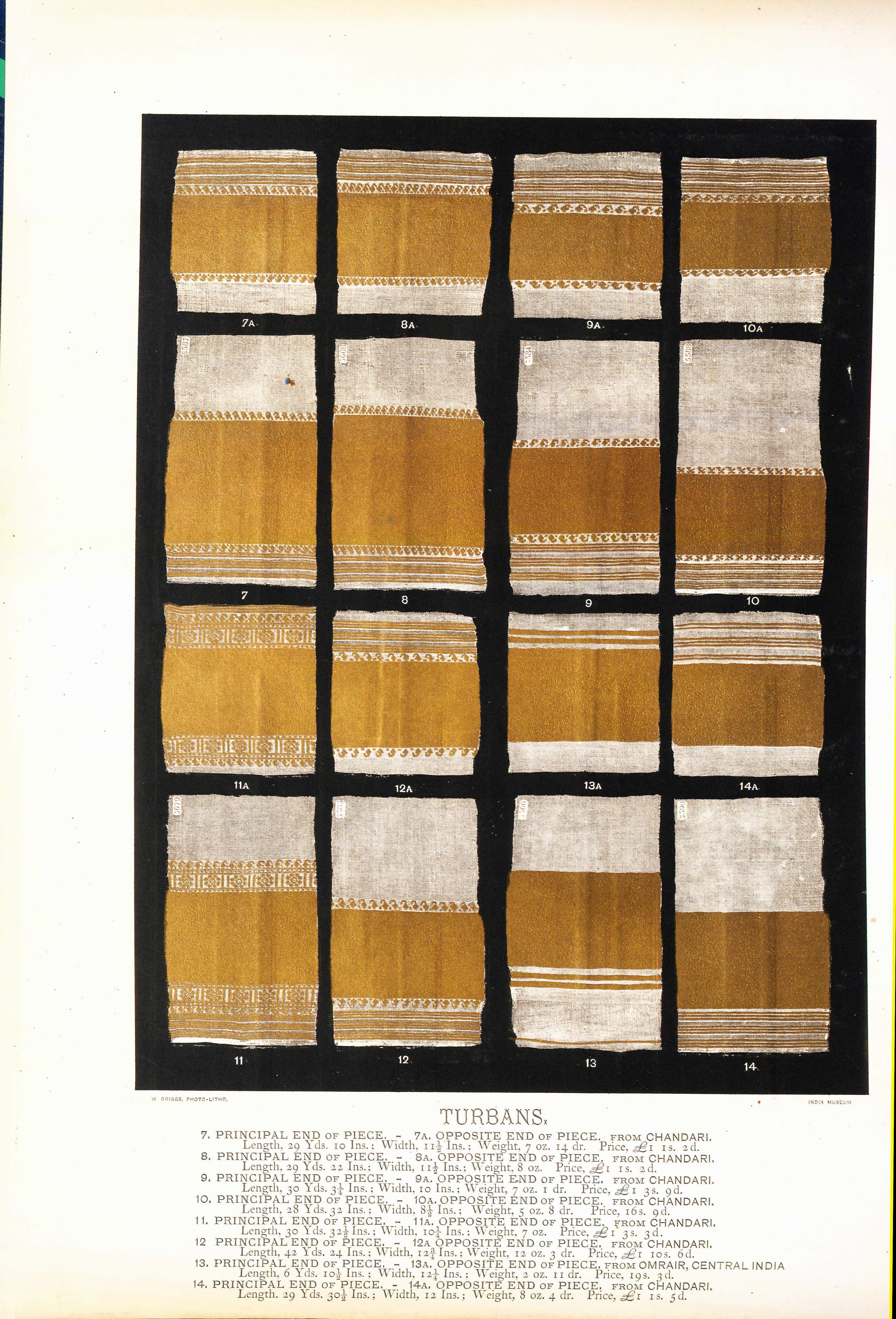

Watson (1827-1892) was appointed the Reporter on Products of India and Director of the India Museum in 1858, and in 1865 he completed his first series of an 18-volume set of textile types collected from various regions in India. With over 700 working samples of fabrics, Textile Fabrics of India provided an invaluable source for understanding the texture and designs desired by the people of India[1]. Watson accompanied this sample collection with his 1866 publication Textile Manufactures and the Costumes of The People of India, a book dedicated to explaining the production methods and uses of his collection of samples.

In the book, Watson declares, “the machinery and skill of Britain may thus do a present service to India, by supplying her with material for clothing her people at a cheap rate—an end to which these collections must certainly lead by showing the home manufacturer what it is that the natives require.” This statement reveals the motives behind the British manufacturers’ desire for a detailed understanding of Indian designs. As the Industrial Revolution helped improve production methods, British manufacturers could mass-produce textiles comparable to those produced in India, but at a much cheaper rate. They would then sell the cheaply made product to the Indian people for profit. By 1870, £80 million worth of British exports to India were textiles[2]. This had a devastating effect on the Indian handloom industry, causing drastic reductions in the number of handlooms and employed weavers. Nonetheless, the British considered the arrangement to have benefits for both countries; they believed that the unemployed weavers could be put to work producing cotton, silk and wool for British manufacturers[2].

In 1873 Watson came out with his second series of “Textile Fabrics of India”—this series contained over 1000 working samples. It was poorly distributed compared to his first series, due to changes in management at the India Museum where Watson worked. George Birdwood, the custodian of the art collection, desired to keep India as the ‘ideal artisan society.’ He chose to focus on preserving the collection rather than distributing it[1]. Today, fourteen volumes of Watson’s twenty volume second series are contained within The Cooper Hewitt Library’s rare book room. The large pale boxes are stacked on top of each other, and after I manhandled them into the reading room, I flipped through one after another and marveled at the preserved samples. Despite its damaging impact on the Indian textile industry, Watson’s collection has had many benefits. In the 1800s, his bold, colorful, exotic collection helped break the mold of traditional Victorian patterns[3]. Our modern day access to the samples Watson preserved gives us an appreciation of the extraordinary textile products of the handloom industry, as well as a deeper understanding of Indian cultural clothing.

[1] Swallow, Deborah. “The India Museum and the British-Indian Textile Trade in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Textile History 30.1 (1999): 29-45. Web.

[2] Lyons, Agnes. “The Textile Fabrics of India and Huddersfield Cloth Industry.” Textile History 27.2 (1996): 172-94. Web.

[3] Thomas, Rupert. “The Rajah Trade.” World of Interiors June 1994: 130-131. Web.

One Comment

Thanks to revealing the original textile history of the Indian subcontinent.Especially the title, genuinely just love it.