Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ new exhibition, “Nature of the Book“, explores the use of natural materials in books from the hand-press era, from the mid-1400s through the mid-1800s. One of the materials the exhibition examines is leather, which was commonly used for book coverings.

One of the leather-bound books we highlight is Mark Catesby’s magnum opus, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, published between 1729 and 1747. This lavishly illustrated two-volume set is the only known contemporaneous account of the flora and fauna of the American colonies.

Mark Catesby traveled to the American colonies in 1712 with his sister. During his stay he collected botanical seeds and specimens, returning home to England in 1719. He spent the next twenty years producing The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. He sold the book via subscription, releasing it in eleven parts over nineteen years. He gave explicit instructions to wait for all of the parts to be complete before binding the parts in two volumes. Few owners were patient enough to wait for the Appendix before binding.

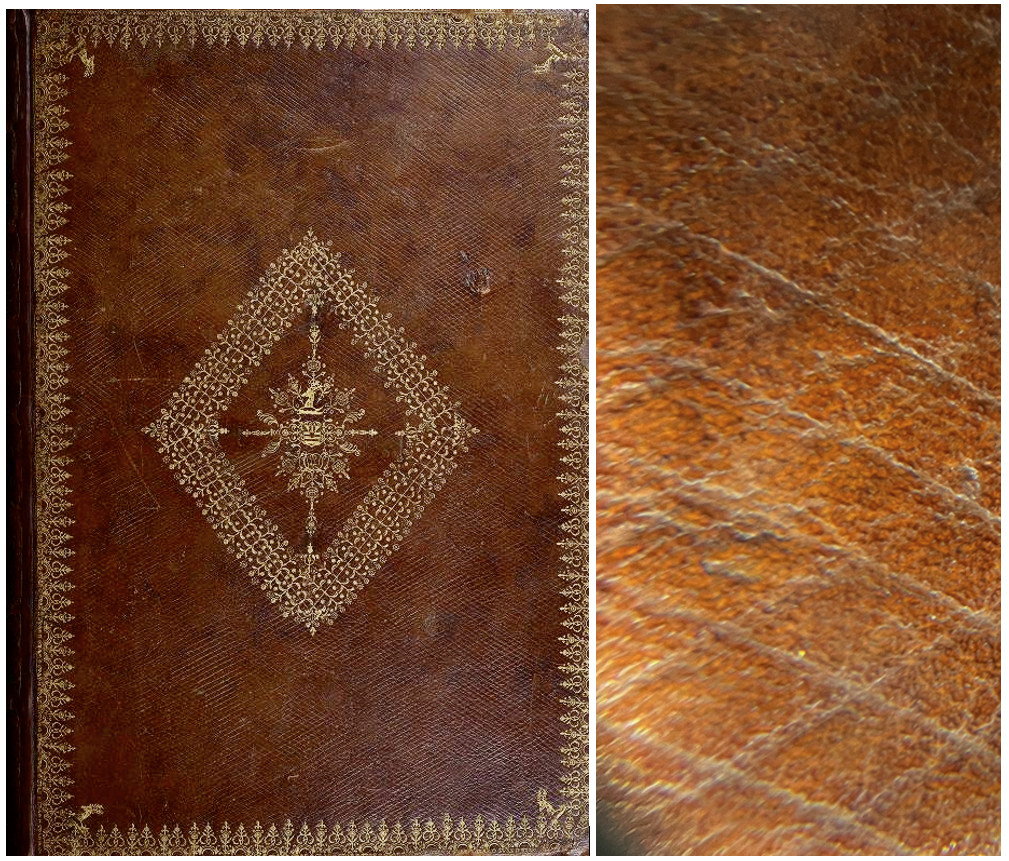

The original owner of the copy in the exhibition was Cromwell Mortimer, Secretary of the Royal Society. During the Hand Press era (1450-1850) books were printed but left unbound so that the purchaser could customize the binding, including covering materials and decorative endpapers. Cromwell Mortimer likely chose to have the volume bound in one of the most luxurious materials of the time, Russia leather, known as Yufte in Russia.

As the name suggests, this leather was imported from Russia via the Baltic Trade Routes. The leather has unique characteristics: a diamond shaped pattern, a reddish-brown color, and the aroma of birch oil. Russia leather is vegetable-tanned in the same manner as other leathers with some key differences.

Traditional vegetable tanning is the process of taking an animal hide, cleaning it thoroughly, soaking it in tannins (from tree bark, wood, galls, fruit, or other plant matter), drying it, and processing it to keep it flexible. In the case of Russia leather, willow bark is the traditional tannin used as it is found abundantly throughout the country. The other differences are in the processing of the leather. Birch oil, with its distinctive odor, was added at the end of the tanning process to keep the leather flexible. The diamond shaped pattern of the leather was originally imparted with sticks and later via a specially created grooved cylinder that was weighted and rolled across the leather in two different directions to create the pattern.

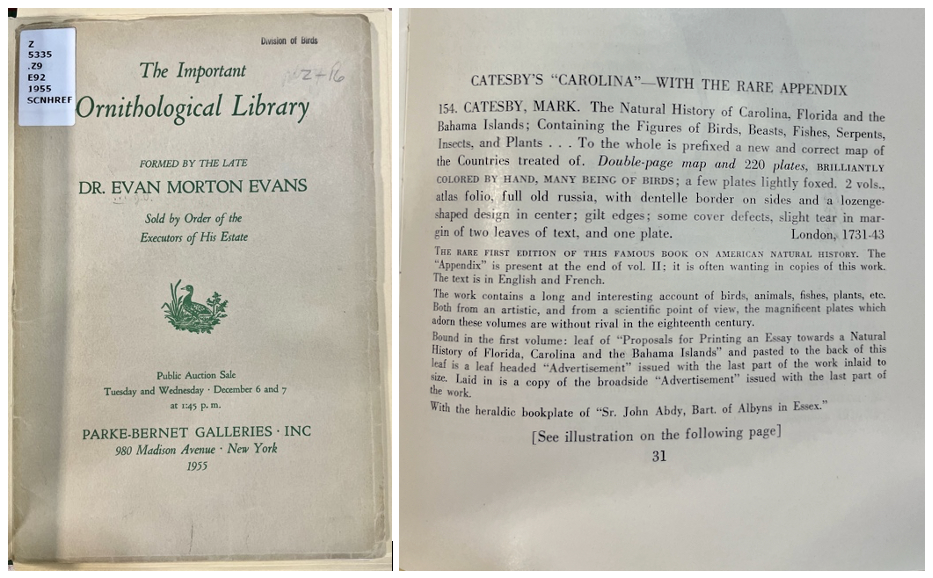

It can be difficult to distinguish Russia leather from diced leather. Additionally, the birch oil odor dissipates over time. However, we have several helpful clues that aid us in identifying the leather used on this binding. The first is the original 1955 catalog of the sale of the Ornithological Library of Dr. Evan Morton Evans. Our copy was purchased in that sale and is described on page 31 as being bound in “full old russia.”

The second clue comes from the pictures and descriptions of Russia leather that were found in the Metta Catherina shipwreck, discovered in 1973. The ship set sail from Saint Petersburg to Genoa in 1786 with a cargo that included rolls of Russia leather when it sank off the coast of Devonshire. The rolls of Russia leather from the Metta Catharina remained preserved for over two hundred years. Some of the leather is now in research collections where the curators of the exhibition were able to examine a piece of it in person.

The third avenue we explored was the source species of the hide. Each species has a unique pore structure that is revealed when the leather is viewed under magnification. In the case of the Catesby binding the species appears to be calf. Peptide Mass Fingerprinting (PMF) is another option for identifying the species of origin of leather. While the accuracy rate is very high a sample of the leather is required for this testing, so we opted for the non-invasive pore structure method. Russia leather could be made from a variety of species including calf, reindeer, goat.

The story of Russia leather continues to be a source of fascination today. While the process was not a secret, re-creating Russia leather proved difficult. Tanneries in England, France and Germany attempted to re-create the leather, but the results were not as durable as the imported Russia leather. In the early 20th century this leather became one of the symbols of the exiled Russian population after the 1917 Revolution, particularly in Paris. One of Coco Channel’s early perfumes, Cuir de Russie, evokes the scent of Russia leather. After the revolution, the technique was thought lost until 2016 when the Parisian luxury leather goods manufacturer, Hermès, partnered with a British tannery to successfully recreated Russia leather.

Be First to Comment