Rare book cataloging can require some detective work. A recent case for me involved a record of ancient coins in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, transferred to the Smithsonian’s Dibner Library for cataloging from the National Museum of American History’s National Numismatic Collection. This is also a tale of how a book can reveal unexpected histories.

Personally, the study of coins, medals and paper currency (numismatics) is not a subject of great interest. But Oxford—that beautiful, ancient, romantic city—has long enchanted me.

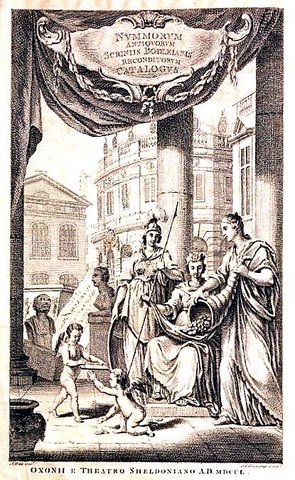

The catalog, Nummorum antiquorum scriniis Bodleianis reconditorum catalogus (1750), compiled by Francis Wise (1695-1767), has engraved plates of rows of individual coins. It is written in Latin, anachronistically, as it was dying out as the scholarly language of the time. In the descriptive text, there are engraved and woodcut head-pieces, tail-pieces and initials that mark the beginning or end of a section and help enliven the pages, standard decorative touches in books of the period.

These ornaments can also act as an anchor on a leaf of set type as it went through the printing press, ensuring an even distribution of ink when there is a lot of blank space on a page. They can be specific to the work at hand and quite elaborate with figures and scenes or a standard printer’s ornament or flowers (fleurons) used interchangeably from publication to publication. Books of the 18th century, expensive to produce, tend to have a lot of decoration. According to the impressive and helpful website, Fleuron: A Database of Eighteenth-Century Printers’ Ornaments, Wise’s title contains a total of 185 printer’s ornaments.

These ornaments can also act as an anchor on a leaf of set type as it went through the printing press, ensuring an even distribution of ink when there is a lot of blank space on a page. They can be specific to the work at hand and quite elaborate with figures and scenes or a standard printer’s ornament or flowers (fleurons) used interchangeably from publication to publication. Books of the 18th century, expensive to produce, tend to have a lot of decoration. According to the impressive and helpful website, Fleuron: A Database of Eighteenth-Century Printers’ Ornaments, Wise’s title contains a total of 185 printer’s ornaments.

The imprint in the catalog was of the Sheldonian Theatre, the great ceremonial hall of the University, designed by Sir Christopher Wren. This structure contained a printing house in the basement until 1713 when the Press was moved to the Clarendon Building. These two landmarks appear in the printer’s mark, a charming pictorial vignette of the greatest architectural hits of the University all lined up.

In collating this catalog of Bodleian coins, I came across something unexpected. Adorning one page was a large etched view of a garden that struck me as too personal and unusual to be incidental. There is a Georgian manor house along with a small classically designed temple in the background, showing landscape terraces with rusticated walls and an arch through which water cascades into a pool, lined with lush plantings. The garden lacked the rigid formality of an earlier period. The scene did not appear to be of one of the inward-looking quadrangles or cloisters of one of the Oxford Colleges nor of its Botanic Garden. Further on was a second picture, another landscape of a framed vista with carefully placed trees. The distinctive spires of Oxford rise in the far background. What was the story here?

Woodcuts and type are a relief printing process. Ink is applied to the upper surface to be transferred to paper. In intaglio printing—engraving, etching or a combination of both—the ink is applied to incised lines so the pressure of the press transfers the image. As an engraved copperplate, these illustrations would have been printed independently of the text—that is, the leaf would have been sent through the press a second time. With that additional work, why did these landscape images, apart being of the nearby Oxfordshire countryside, end up in this book of coins?

Woodcuts and type are a relief printing process. Ink is applied to the upper surface to be transferred to paper. In intaglio printing—engraving, etching or a combination of both—the ink is applied to incised lines so the pressure of the press transfers the image. As an engraved copperplate, these illustrations would have been printed independently of the text—that is, the leaf would have been sent through the press a second time. With that additional work, why did these landscape images, apart being of the nearby Oxfordshire countryside, end up in this book of coins?

Part of the answer was easily dug up. In trying to identify the engraver of the frontispiece and title page vignette (something we do in our rare book cataloging at the Smithsonian), the story began to unfold. The images are signed J. Green and Jas. Green as both the artist (designer) and the illustrator (engraver-etcher). As you can imagine, there have been a lot of James Greens in the world. As I was trying to pin down the name, an online search came up with an art dealer’s offering of the engraver’s proof of the Oxford scene that appears on the title page (although the artist is mistakenly identified as John Green). The ending paragraph of the description was all about our author here, Francis Wise. He created a celebrated garden on the hillside overlooking Oxford. And he was a librarian. Now this was fun and interesting.

The publication, Oxoniensia, of the Oxford Architectural & Historical Society, helped further. “A History of the Garden of Elsfield Manor, Oxford,” by Paige L. Johnson, provides some background information on Francis Wise and details his story within the landscape (link to the article here). He “had an ambitious but ultimately second-rate career” as a librarian (ouch). Following positions as Bodleian Sub-Librarian and Keeper of the University Archives, Wise became first Radcliffe Librarian. In the words of Strickland Gibson, he was “the custodian of a magnificent library which for some years was little cumbered by books and almost entirely unencumbered by readers.”

Wise had time for indulging his hobbies: collecting coins (particularly Anglo-Saxon ones), and gardening.

Wise had been tutor to, and life-long friend of, Francis North, son of the 1st Earl of Guildford (dedicatee of the Bodleian catalog of coins), who gave him a lease on the house at Elsfield, where he was also curate, in 1726. He later asked of his patron if he might have “a little bit of ground” for a garden.

In the few acres of Elsfield Manor, Wise laid out an astounding array of terraces, paths, canals, waterfalls, ponds, and garden edifices among plantings to enhance the setting. With little means (he undertook tutorial work to supplement the small salary of a librarian), Wise was never able to embark on a Grand Tour of the Continent as had his wealthy pupil. But the librarian was an antiquarian with access to books that illustrated the picturesque ruins that an English gentleman of the 18th century would visit abroad. With a triumphal arch, the Tower of Babel, Roman as well as Druid temples, an Egyptian pyramid, and columns with faux ancient inscriptions, a fanciful world in miniature sprang up in the Oxfordshire countryside.

Wise developed his imaginative landscape from 1740 to 1767. It became well known, appearing in local guidebooks. The librarian-gardener hosted many visitors, including Samuel Johnson who visited three or four times just before his Dictionary was to be published. James Boswell noted that Wise had created a garden “in a singular manner but with great taste.” But in the present day, Elsfield has largely been overlooked by garden historians. It is not mentioned in The Oxford Companion of Gardens, an indispensable volume that details so many estates and figures in history. The property, still privately owned (if diminished), is a rare example of an academic, non-aristocratic garden of the 18th century.

The view, so carefully framed in the landscaping, has been largely preserved by various Trusts. But the ornamental structures have all but disappeared. Lacking the necessary funds, Wise likely had the edifices fashioned not out of stone but constructed from wood and plaster. Given the prohibitive costs of book production, he also could not have afforded to have had printed a lavish record of his landscape creation. Gardening is an ephemeral art that Wise knew would not last through the ages. This helps to explain how two garden views ended up in a catalog of coins.

As was the practice at the time, Wise would have been largely responsible for securing the funds for his publication, Nummorum antiquorum scriniis Bodleianis reconditorum catalogus. The British Library has in its collections the author’s proposal for raising funds by subscription. It promised “Not only Draughts of the most curious Coins, but a Series of the several sorts of Greek, Roman, &c. shall be engraved from the Originals and printed upon Twenty large Copper Plates in Folio.” This was an expensive undertaking. Wise would have commissioned the artist, James Green, and apparently diverted him over to the Manor to portray his garden.

How touching to think of the eccentric librarian slipping in pictures of Elsfield, his other magnum opus, into this Oxford imprint, to ensure it would be commemorated and preserved in a collection such as the Bodleian. Unlike the flimsy edifices adorning his garden and plantings that would become overgrown or die, his book would last, as it does today in the Dibner Library.

Notes

For more on Wise’s career and the politics of librarian appointments at Oxford see Strickland Gibson, “Francis Wise, B.D.: Oxford Antiquary, Librarian and Archivist” (link here).

The two etched garden scenes from the catalogue had further life. The house and canal view was reworked with the addition of the figures of Wise and Johnson (and two swans) in Graphic Illustrations of the Life and Times of Samuel Johnson of 1835. Later owner of Elsfield Manor, John Buchan (1875-1940), commissioned a woodcut bookplate that replicates Green’s vantage point of the countryside. A version of this image appeared, for a time, on the cover of the serial, Oxoniensis, also in the Smithsonian Libraries collections.

Buchan had settled at Elsfield at the end of the First World War and lived there until his appointment as Governor-General of Canada in 1935. A politian, novelist, historian, and Fellow of Oxford, Buchan used one of Wise’s structures as his study. The garden appears in several of his writings. Virginia Wolf and T.E. Lawrence were among the visitors.

Be First to Comment