The Smithsonian Libraries does not contain an overwhelming number of notable bookbindings in its collections. Unlike some other research institutions, fine or interesting covers are not a collecting focus or reason for acquiring a title. Many of our books have had a hard life, well-used over the decades by staff and researchers in the museums’ departments. These survivors have often been rebound in library buckram (sturdy but oh so boring) or been slapped with labels and barcodes (from an earlier time of library practice). So it is always a thrill to come across a striking specimen of an original binding.

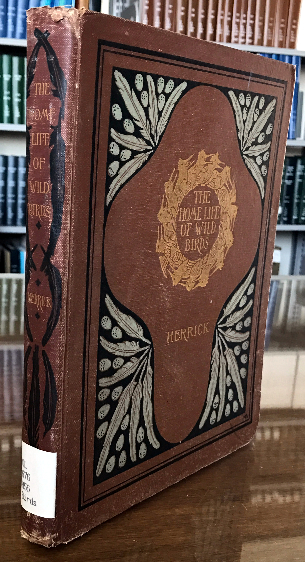

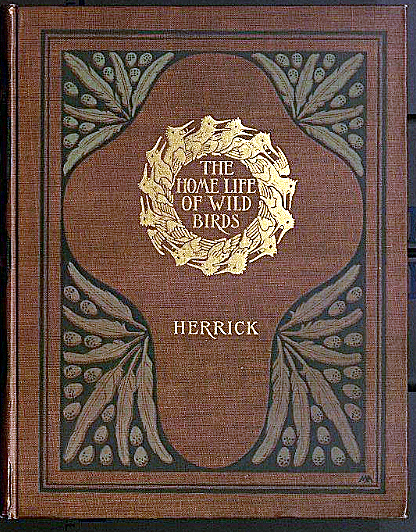

Cataloging Francis Hobart Herrick’s The Home Life of Wild Birds (New York, 1901), I first focused all attention on the front cover. It is an example of publisher’s, or trade, binding. From the early part of the 19th century, these case bindings, often of cloth, replaced the temporary paper boards of a text found at the bookseller’s shop (a purchaser would then have the new book bound in leather or other desired material at their own expense). This represents a shift in the economics of the book trade from an earlier period. Reflecting the demands of the ever-increasing readership and competition between publishing houses, these edition bindings were, in effect, advertisements. This book, published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, with its use of colors and blocking in gold and curvilinear elements of Art Nouveau, is a sophisticated example of the new art form as it evolved from about 1880.

The book’s textured brown cloth, suggestive of a tree trunk, has black rules enclosing the design. Creating an elaborate frame, the corners of the quatrefoil layout are speckled bird eggs and feathers in a lovely pattern suggesting fans. A cartouche enclosing the title is a lively wreath of chirping, baby kingfishers in a nest. This central ornament is repeated in blind on the back cover; green feathers and the title in gilt decorate the spine. It is a carefully worked-out scheme.

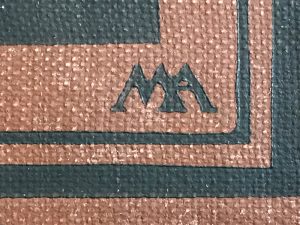

I noticed in the lower right corner a small monogram, intertwined “M A,” and, I blush to admit, while vaguely familiar, could not recall.  There are wonderful online resources and exhibitions of publishers’ bindings of 19th to the early 20th centuries in America, featuring scholarly work by conservators, bookbinders, librarians, and other historians, many the protégés of the late, great Sue Allen and her course at Rare Book School. The name Margaret Armstrong was identified quickly as the artist-designer here, thanks to these sources.

There are wonderful online resources and exhibitions of publishers’ bindings of 19th to the early 20th centuries in America, featuring scholarly work by conservators, bookbinders, librarians, and other historians, many the protégés of the late, great Sue Allen and her course at Rare Book School. The name Margaret Armstrong was identified quickly as the artist-designer here, thanks to these sources.

From the 1880s, publishers paid accomplished artists to produce eye-catching compositions for books as a means of boosting business. Employment in cover design was equally competitive for men and women as the demand for up-to-date trends increased. One of the most celebrated artists in the field, both in her own time and current collecting interests, is Margaret Armstrong (1867-1944).

Herrick’s The Home Life of Wild Birds contains tell-tale signs of a Margaret Armstrong binding, even if it were not signed (the initials “M A” did not always appear in her designs). The long, trailing arm of the letter R and the use of flowers, vines or feathers for framing are distinctive. The lack of strict symmetry and application of elements of nature reflect the artistic movement of Art Nouveau. As the daughter and sister of stained glass artists, Armstrong often used the bold colors and outlining of that type of decorative art. In addition, her designs—obviously here in this work—directly relate to the contents within the covers.

The arrival of the commercial dust jacket around 1910 brought on the decline of the once-thriving industry of decorative binding designers. After a career of producing some 270 designs, Armstrong adapted and turned to her own writing and illustrations or produced for the works of her large, creative family. Margaret Armstrong grew up in a well-to-do family of a Bohemian bent, in a Greenwich Village townhouse in New York City that attracted such artists-friends as Stanford White (the famous architect also designed book covers) and John La Farge.

On the inside front cover of the Smithsonian’s copy of Herrick’s The Home Life of Wild Birds were bookplates that did not need any further research. They were of Jonathan Dwight (1858-1929) and Marcia Brady Tucker, who I had encountered many a time. There are more than a couple hundred books cataloged in the Smithsonian Libraries that were once in their collections. We do try to identify and trace all former owners in our records.

Marcia Brady Tucker (who died in 1976), grew up with immense wealth as the daughter of one of the richest men in America. With her husband Carll Tucker, she resided in mansions at 733 Park Avenue, Mount Kisco and Hobe Sound, Florida and cruised to far locales on birding expeditions on their three-masted schooner, The Migrant. Her Upper East Side home hosted many an ornithologist. She was director for two terms of the National Audubon Society and served on the International Council for Bird Preservation and the American Ornithologists’ Union. She funded various avifauna studies and exhibitions and attended many professional conferences. The Marcia Brady Tucker Foundation, based in Easton, Maryland, still awards grants for various causes, including the environment. In addition, there is the Marcia Brady Tucker Curatorial Fellowship at the Yale University Art Gallery.

Another legacy was Tucker’s great collection of bird books, many of which came to reside in the libraries of the National Museum of Natural History (other recipients were Cornell and Kansas Universities and The Audubon Museum in Henderson, Kentucky). Previously, she had purchased the library of ornithologist and fellow New Yorker Jonathan Dwight, hence his bookplate in Herrick’s work. A title once owned by Tucker is easily identified, even if these ownership marks are missing. Her librarian usually had penciled in a neat hand a subject or classification on the front pastedown and a collation note, at the top of one of the preliminary leaves or title page.

While Margaret Armstrong’s life and career are well documented and celebrated, Marcia Brady Tucker has mostly faded in the historical record, no longer noted as one of the influential bird preservationists nor as a prominent book collector. This March, Women’s History month, we commemorate both accomplished, distinct individuals as seen in the physical evidence in this one book.

NOTES

The Smithsonian’s Dibner Library contains a file of some carbon copy correspondence relating to Marcia Brady Tucker’s library. It suggests most of the collection resided in the Mount Kisco home in Westchester County, New York and that she employed a librarian.

The Biodiversity Heritage Library is to be commended for including book covers and all preliminary leaves in its digitization practices. The copy here from Cornell University Library.

Allen, Sue. Gleaming Gold, Shining Silver: Nineteenth-Century Book Covers from the Collection of Leonard and Lisa Baskin. The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, 2002.

Rare Book School at the University of Virginia has a large holding of Margaret Armstrong’s work.

“Beauty for Commerce: Margaret Armstrong”

“Publisher’s Bindings Online, 1815-1930: The Art of Books”

“Art Bound: Margaret Armstrong and the Decorative Designers”

Minsky, Richard. “American Decorated Publisher’s Bindings, 1872-1929”

Be First to Comment