Author’s note: Elizabeth Gould was a 19th century artist responsible for some of the most historically significant images of birds ever published. She was also a devoted wife and mother. It is sometimes difficult to reconcile both of these aspects of her life through our modern lens of 21st century social issues and feminism; it can be tempting to paint her story as that of a woman repressed by antiquated gender roles, and to speculate on her career trajectory had she not tragically died shortly after the birth of her eighth child. However, while history strives to be objective, it impossible to completely purge our modern sentiments from the retelling of her story, so it is important to strive to tell it based on documentary evidence rather than speculation. Elizabeth’s life was very eventful for being so short, as we shall soon see, so it is not difficult to craft an exciting biographical narrative for her. The difficulty comes, instead, from trying to ensure that she maintains a degree of agency in her own story. I have tried to write this post in such a way that is respectful to both Elizabeth and the time in which she lived.

The beautiful lithographs produced by Elizabeth Gould show lively birds of all shapes and colors performing mating displays, protecting their young, and interacting with their environments. A far cry from the dead-bird-on-stick approach to book illustration of the 18th century and prior, Elizabeth’s birds are reminiscent of the more dynamic figures depicted by John James Audubon; in fact, distinguished ornithologist Prideaux John Selby proclaimed “I like [Elizabeth’s illustrations] as well as Audubon’s.”[1] However, it is not Elizabeth’s name on the title page of A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains (for which she lithographed 80 plates) or on the ‘Birds’ volume of The Zoology of the Voyage of the H. M. S. Beagle (for which she lithographed all 50 plates); rather, it is that of her husband, John. A respected taxidermist and ornithologist, John was also a master of marketing, putting out numerous large-format lithography plate books over the course of his career. But John’s artistic skill was not up to the task of such a grand undertaking; instead, he relied on the artistic talents of others, including his wife, to carry his work to new heights.

Elizabeth Gould, nee Coxen, was born in 1804 to a military family in Ramsgate, England. One of eleven children, and the only daughter to survive to maturity, information on how she and her siblings spent their childhood is unfortunately sparse; however, by age 22, Elizabeth had obtained a position as governess to the 9-year-old daughter of the Chief of the Office of the King’s Proctor in London. Being able to work as a governess for aristocracy implies that Elizabeth was highly educated, which was not unusual for middle- and upper-class women of the period: as part of this education, she would have been taught foreign languages, music, as well as to draw and paint in watercolor, gentile pursuits that earned a young lady the epithet of being “accomplished.”

However, the fact that she had to seek employment also implies that her family could not financially support an unmarried daughter. Indeed, she was not overly fond of the job—between teaching the young girl French, Latin, and music, Elizabeth wrote to her mother that her duties as a governess were “miserably-wretched dull,” and that she feared she would soon become “very melancholy.”[2] Thus, her marriage to John Gould when she was 24 in 1829 has been characterized as a “rescue” by some authors.[3] In reality, the rescuing went both ways.

John’s career in ornithology was on the rise at the time of his and Elizabeth’s wedding—by 1828, he had been appointed Curator and Preserver at the Museum of the Zoological Society of London. In 1830, a collection of Himalayan bird skins came across his desk for preservation, which his colleague, N. A. Vigors, was in the process of describing. Familiar with the new printing technology of lithography through the work of one Edward Lear, John put forward a proposal for an illustrated book to show off the new and interesting species contained in the collection. Fully aware that his own artistic abilities did not lend themselves to the subtle medium of lithography, John brought the project to Elizabeth, who at first did not grasp the gravity of her husband’s request. “But who will do the plates on stone?” she reportedly asked. “Why you, of course!” John replied matter-of-factly.[4]

No record exists of how Elizabeth felt about suddenly being designated the family draughtswoman. However, executing her new role cannot have been easy for her from a purely physiological standpoint: pregnant with her and John’s first child, she nevertheless spent hours transferring her specimen drawings onto stone in anticipation of the publication of the first batch of plates for the work. She gave birth to a son, John Henry, only days after the plates were sent to subscribers.[5]

As previously stated, Elizabeth’s name is absent from the title page of what became A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains; her contribution is briefly mentioned in the preface of the work, which simply states that her “well-known abilities” were employed in “delineating these birds.”[6] Each of the plates bears a small artist’s credit on the lower left—“Drawn from nature on stone by E. Gould”—but none of them feature her signature. Edward Lear, who John enlisted to teach Elizabeth lithography methods, incorporated his signature into much of his work, so it is somewhat curious that she elected not to sign her pieces.

Her work was well-received in ornithological circles, and N. A. Vigors was so impressed by her artistry that he named a species of colorful sunbird in her honor. But it was John who received the lion’s share of professional accolades. The success of Century spurred John to undertake a much larger survey of European birds, which he initiated while the final parts of Century were still being delivered to subscribers. This ambitious publication, which became the 448-plate Birds of Europe, required John and Elizabeth to travel extensively in continental Europe, visiting natural history collections and observing and collecting specimens in the wild. Being able to see living, moving birds enabled Elizabeth’s artistic talent to improve immensely; it is during this publication that she truly began to show the lively interactions between males and females of species, and incorporating movement into her figures that made them look as though they could fly off of the page at any moment.

However, the artist credit on the lower left corner of the plates of Birds of Europe does not just bear Elizabeth’s name. Instead, her initial E. is preceded by a J., as John claimed artistic credit for the composition of the designs.

This line would remain the norm throughout the rest of the publications they worked on together. In his preface to Birds of Europe, John describes how Elizabeth drew and lithographed the pieces, but credits himself for the “sketches and designs.”[7] Documentary evidence tells a different story. The Ralph Ellis Collection, housed at the University of Kansas’ Kenneth Spencer Research Library, contains a number of sketches that indicate that, rather than arranging the composition, John would either make minor changes to or simply approve Elizabeth’s sketches that became the final designs.[8]

Observation, drawing, printing, and publication of Birds of Europe took a total of five years, during which Elizabeth gave birth to five more children, only three of whom survived infancy. Also during this time, John employed Elizabeth to draw the plates to accompany his text on the bird specimens brought back by the young naturalist Charles Darwin from the voyage of the H. M. S. Beagle. Among these specimens were the now-famous Galapagos finches, which Darwin referred to when formulating his theory of natural selection in his 1859 On the Origin of Species. Elizabeth’s name is completely absent from the plates.

The work that truly established John Gould as a master of ornithological publication was Birds of Australia, published over eight years from 1840-1848. After his experience with Birds of Europe, John had realized the importance of field observation to the quality of his publications. He subsequently arranged for Elizabeth, their eldest child John Henry, their nephew Henry Coxen, zoologist John Gilbert, servants, and himself to make the voyage to Australia in 1838, a trip that was in part made possible by Elizabeth’s family. Her two brothers, Charles and Stephen, had established farms in New South Wales, and had already sent a number of Australian bird specimens back to the Goulds for description and lithography, and the Gould party even used their property as a base for the latter months of their two year stay in the colony.

It is this period of Elizabeth’s life that is most well-documented, thanks to the letters she wrote to her mother in England, as well as her travel diaries. It was also likely one of the most difficult periods of her life. Forced to leave three of her children behind to accompany John on his scientific pursuits, she was distraught; she was so emotionally plagued by the prospect that she was nearly unable to board the ship on the day of their embarkation.[9] It is unclear how John finally managed to persuade her to go up the gangplank, but it is clear from her correspondence that she remained deeply concerned about the wellbeing of the children, the youngest of whom was only six months, as well as her mother.

Rather than being entirely maudlin, her letters also contain anecdotes of John’s collecting prowess (“he has already shown himself a great enemy of the feathered tribe”), her reluctance to participate in a ball held for the Queen’s birthday (“Don’t fancy I attempt dancing—no, no. I am well content to look on.”), and the ambiance of a campsite in New South Wales (“where nature appeared in her wild luxuriance”).[10] What they do not discuss, unfortunately, is her art. Her surviving sketches and the lithographs they became have been left to speak for themselves.

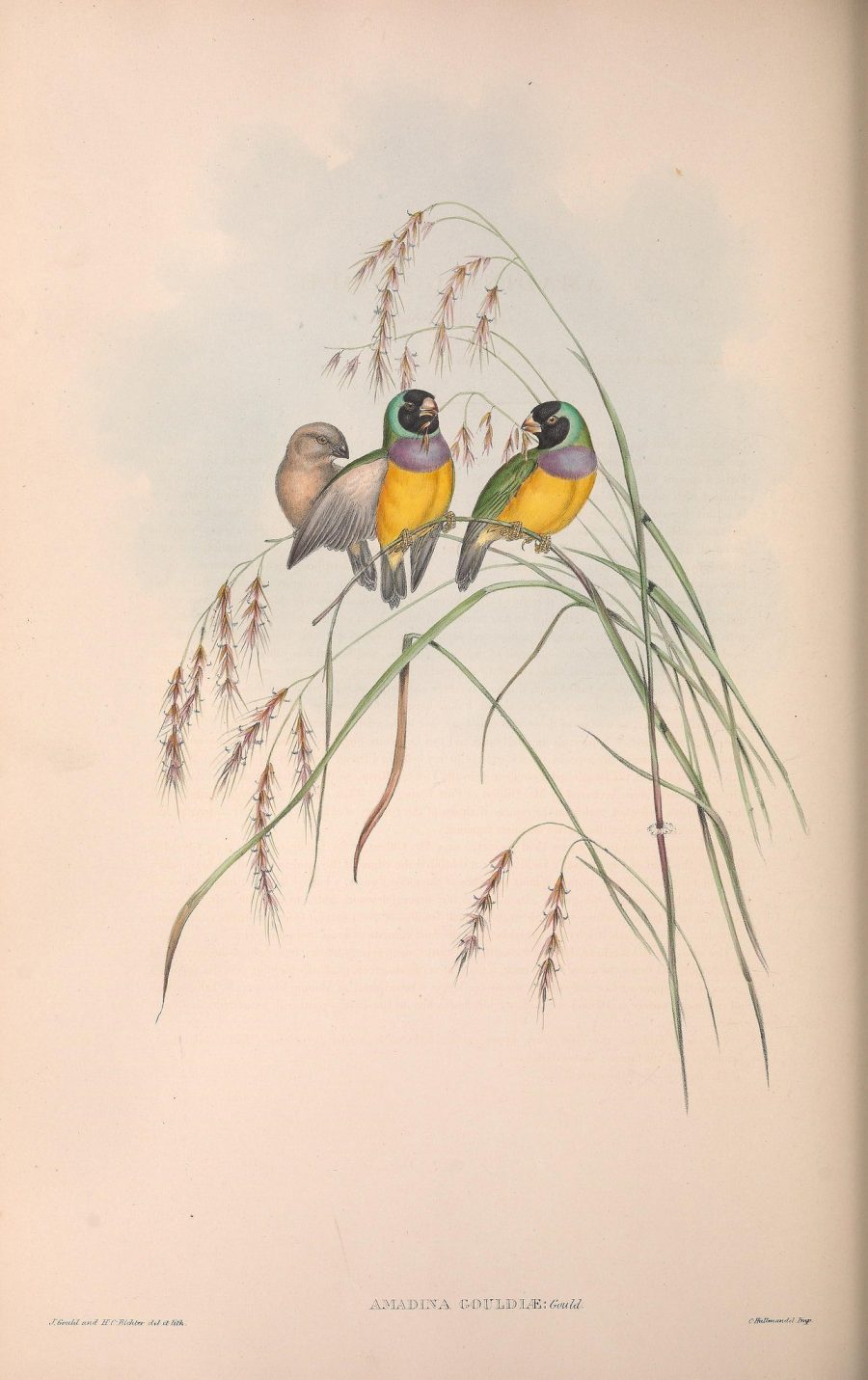

When the Goulds returned to England in August 1840, they brought back sketches, specimens, and another child—Elizabeth gave birth to a son, Franklin, in Tasmania. The first part of Birds of Australia was due to be published in December of that year, so John and Elizabeth quickly got to work on the text and lithography. Elizabeth had managed to transfer 84 of her drawings onto stone by August 1841, but tragically, she would not live to see the project through to completion. A few days after giving birth to an eighth child, Sarah, Elizabeth was struck by puerperal fever and passed away. She left John with multitudinous sketches and six children. There is no record of how this affected John emotionally. However, he memorialized her in the best way he knew how: he named a multicolored finch in her honor, and described her devotion to the family publication pursuit in the accompanying text.

Elizabeth’s life is inexorably linked and influenced by that of her husband John. The way he credited (or rather, failed to credit) her contributions is objectively bad practice, and some of John Gould’s other collaborators denounced him years later; notably, upon hearing of John’s death in 1881, Edward Lear wrote that John “owed everything to his excellent wife, and to myself, without whose help in drawing he had done nothing.” However, researchers combing Elizabeth’s correspondence and diaries have found no record of her dissatisfaction with the process. It is frustrating that such a talented woman has left behind so little in the way of information about her feelings toward her art; but the delicacy and care by which she portrayed her subjects can convey nothing else than love.

The Biodiversity Heritage Library holds many of Elizabeth Gould’s works, including the Smithsonian Libraries’ copies of A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains , The Birds of Australia,and The Birds of Europe, for anyone to view and appreciate for themselves.

[1] Isabella Tree. The Bird Man: The Extraordinary Story of John Gould. London: Ebury Press. 2004.

[2] Chisolm, Alec. 1964. “Elizabeth Gould: Some “New” Letters.” Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 49(5): 10.

[3] Roslyn Russel. The Business of Nature: John Gould and Australia. Canberra: The National Library of Australia, 2011.

[4] Richard Bowdler Sharpe. An Analytical Index to the Works of the Late John Gould, F. R. S., with a Biographical Memoir and Portrait. London: Henry Sotheran, 1893.

[5] Russel, 2011.

[6] John Gould. A Century of Birds from the Himalayas. London, 1831.

[7] John Gould. The Birds of Europe. London, 1837.

[8] Melissa Ashley. “Elizabeth Gould.” John Gould: Bird Illustration in the Age of Darwin. 2014. https://exhibits.lib.ku.edu/exhibits/show/gould/about/elizabeth_gould

[9] Ibid.

[10] Russel, 2011.

3 Comments

I have a “print” of Harlequin Humming Birds

signed E. J. G. It is simple and primitive and

I wonder if you can tell me something about

it. I read Rick Wright’s article “Hummingbirds

and Harlequins” on the Biodiversity Heritage

Library Website. So wondering if it is a farce.

print is on J. Whitman Turkey Mill paper 1827.

Would like to send you scan of print and signature.

Thanks,

Jeanine Sutherland

The last few days I have been obsessed with finding the artist who did the beautiful drawings of birds that are either mistakenly attributed to Charles Darwin himself or that have no reference at all to an artist. Yours is the first article I’ve found that leads to the answer.

It’s scandalous how this happened in the 1800s, and scandalous that it is happening even now, with Elizabeth Gould still not being referenced when those drawings accompany Darwin’s work.

Thank you!

[…] post was originally published on the Smithsonian Libraries’ blog. It is reproduced with permission from the Author, Alexandra K. […]