This post was written by Joanna Shuker, an intern working on the World of Maps project during Fall 2018. It is one of two complementary features. Please also read Melissa Carrillo’s insights, posted on the Smithsonian Institution Archives blog, The Bigger Picture, February 26th, 2019.

Funding from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee allowed fellow conservation intern Melissa Carrillo and me to undertake a sixteen-week conservation project at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). The project was to work with fifty selected maps from the NMNH departments and undertake a survey of the map collection as a whole. The fifty selected maps were chosen for work, as they were deemed important and unique to the museum. The maps varied in size, material and geographic location. This post will mention just some of the highlights from this internship.

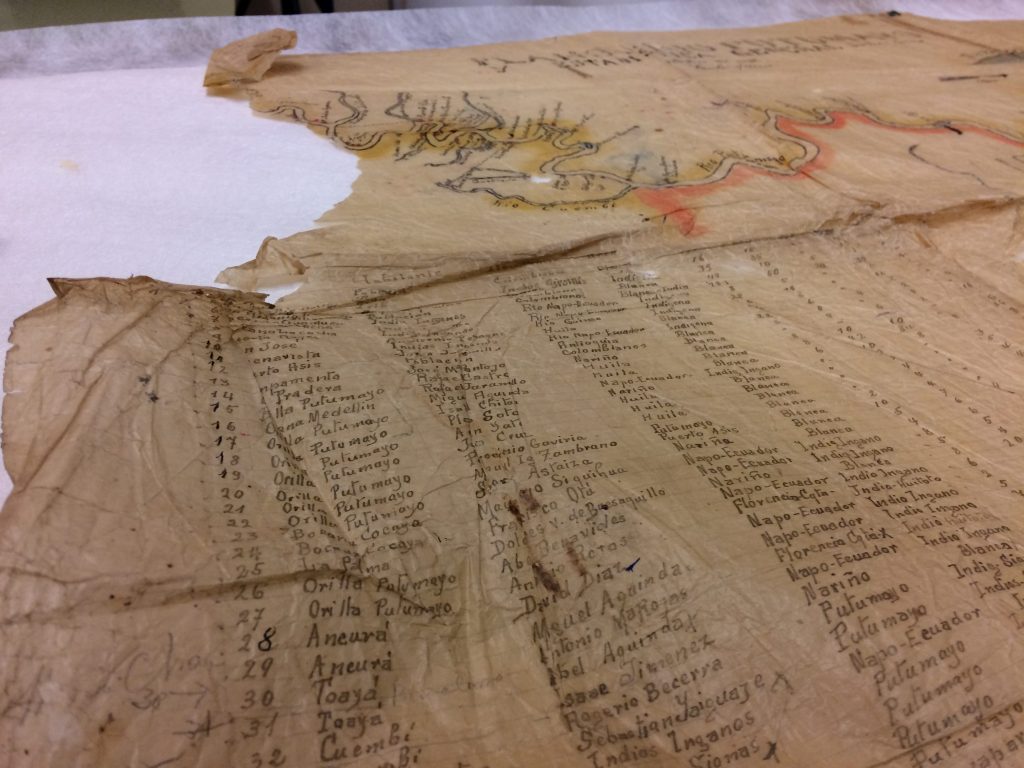

From the beginning and throughout the project I was introduced to new map terminology and map-making processes. I have a passion for maps and expedition history and as it is such a large topic, I am always learning. The NMNH maps are largely documents that were used by researchers to plan trips and to keep data on where collection samples had come from. The maps we worked with during this project were a mix of flat, folded, rolled and bound, from small pocket railroad maps of Texas to large hand drawn maps of the Putumayo River in the Amazon.

Identifying material and printing methods was a large part of the beginning of the project as in order to create detailed condition reports and treatment proposals we needed to understand how the maps were made. A material I had not worked much with before was architectural cloth (drafting linen) which is a starched and calendered cloth often used in the architecture and map industry as it is more durable than paper. By correctly identifying materials, you can understand how they behave and match the best repair materials and adhesives.

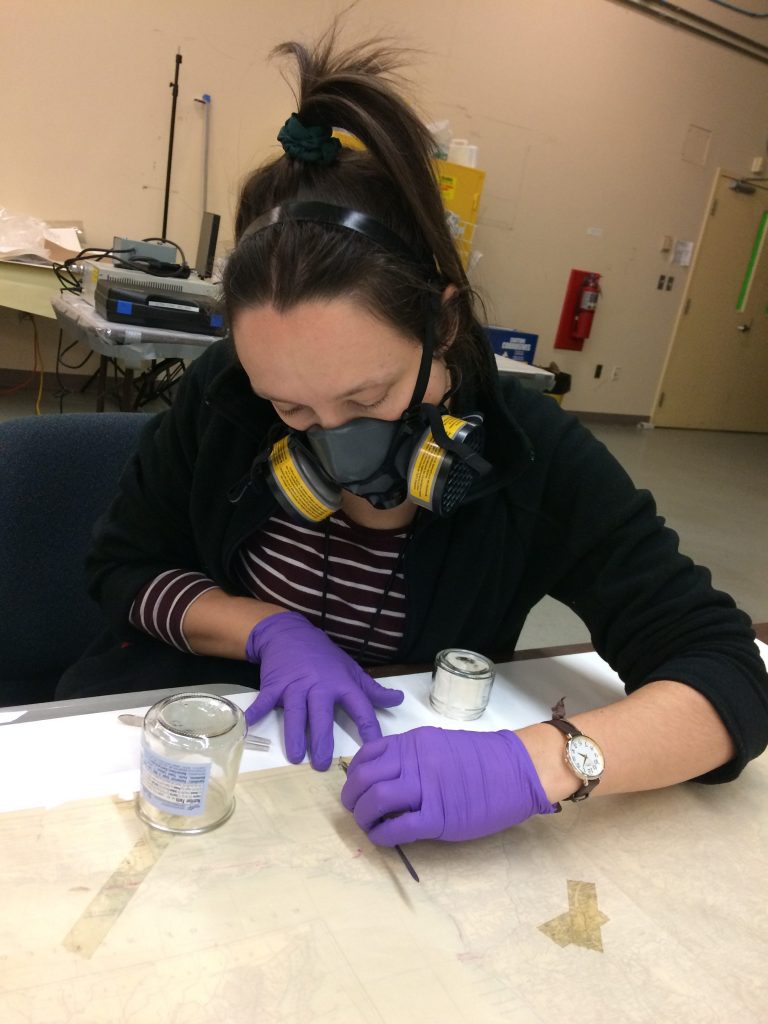

The practical work that I under took during this internship was a mix of using skills that I had already, and learning new skills and methods with new equipment. One piece of equipment, which I had little experience with, was the Preservation Pencil. This tool creates a hot water vapour, which can be used for local humidification. The local humidification was needed to remove creases from the large map of Putumayo that was hand drawn on tracing paper, which can be very water sensitive. Using a small amount of hot water vapour, the creases became relaxed and could be eased flat. To aid the flattening we used magnets. Combined with a magnetic surface on the worktop underneath the map, the magnets helped flatten the paper more quickly than traditional methods. The treatment was done in sections allowing 30 minutes of pressing time, before moving on to the next section. This was very time consuming but allowed other work to be done alongside the treatment of this map. After days of flattening, the map was ready for the next stage of treatment.

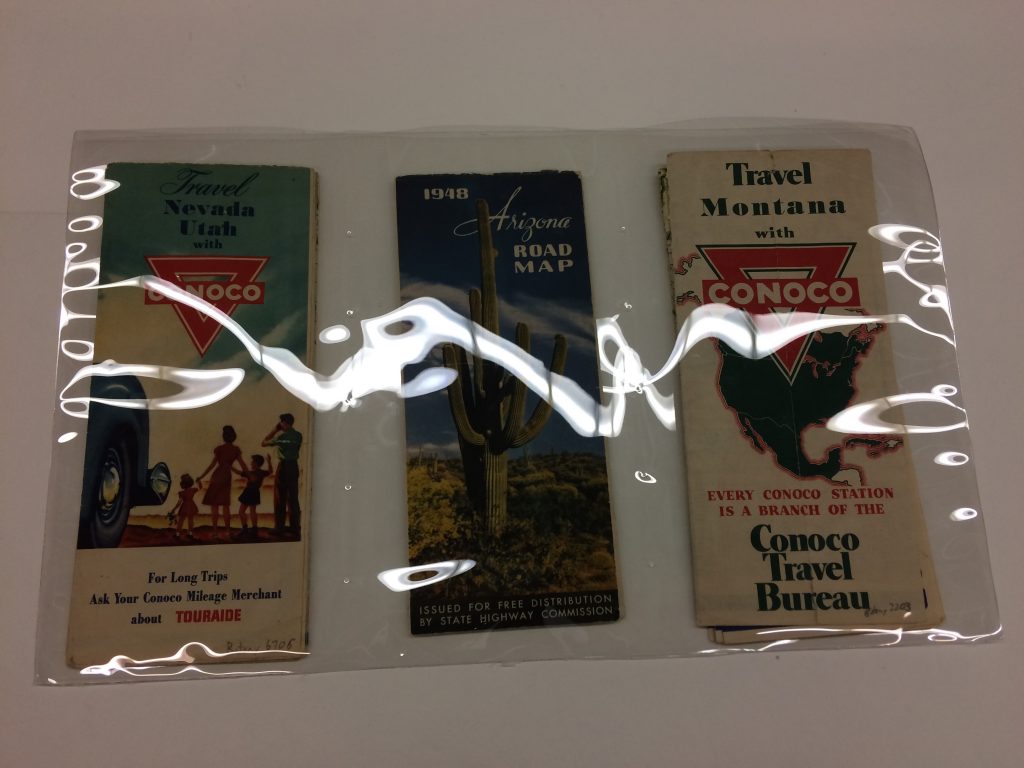

Alongside practical work, discussion was had within the project team to decide the best treatment and storage for some of the maps. Within the fifty priority maps there were a couple of pocket railroad maps that had become detached from the booklet. Conversations as to whether the maps should stay flat and risk disassociation or be folded and re-joined to the booklet were had. To meet conservation best practice, it was decided that treatment should undertaken to repair tears in the map to make it stable for folding and the text block of the booklet re-sewn to reattach loose leaves. The two sections were not joined but instead are now stored in a suitable enclosure together.

The maps are all stored geographically in drawers, which means that there are maps of all sizes within one drawer. During the storage survey of the map collection we noticed that there were some simple housing solutions that could benefit access and long-term stable storage of these documents. To prevent the small folded maps from sliding around the drawer or becoming lodged under large maps, a polyester pocket was designed. The map volunteers could then easily make a row of pockets.

One of the great aspects of this internship was working alongside another intern from a different part of the world. Melissa and I swapped experience stories throughout the project. Melissa taught me how to make methyl cellulose paste which she uses frequently in Mexico but which I have had less experience making.

I am extremely grateful to have had this opportunity and to have learnt skills from the conservators and project staff: Nora Lockshin, Vanessa Haight Smith, Barbara Ferry, Jim Harle and Bob DeMoyer. I also met many lovely staff members who showed us around and gave us tours.

Having the chance to be based for a short time in a city such as Washington DC was a wonderful opportunity; Melissa and I spent many weekends visiting other galleries and museums in the city and enjoying the variety of cultural activities that DC and the surrounding areas have to offer.

Now back in England as a sole conservator I find it incredibly valuable to have gained a varied set of skills and experiences that I can draw on and reference as I continue to build my career.

Joey Shuker, World of Maps Conservation Intern 2018

One Comment

Fascinating story, and great to see the Smithsonian undertaking a survey of its various map holdings and conserving so carefully. I hope Joey Shuker and Melissa Carillo build on this experience and pursue their interest in maps. If they do, they, and readers of this article, may be interested in the Washington Map Society (on Facebook and at http://www.washmapsociety.org).