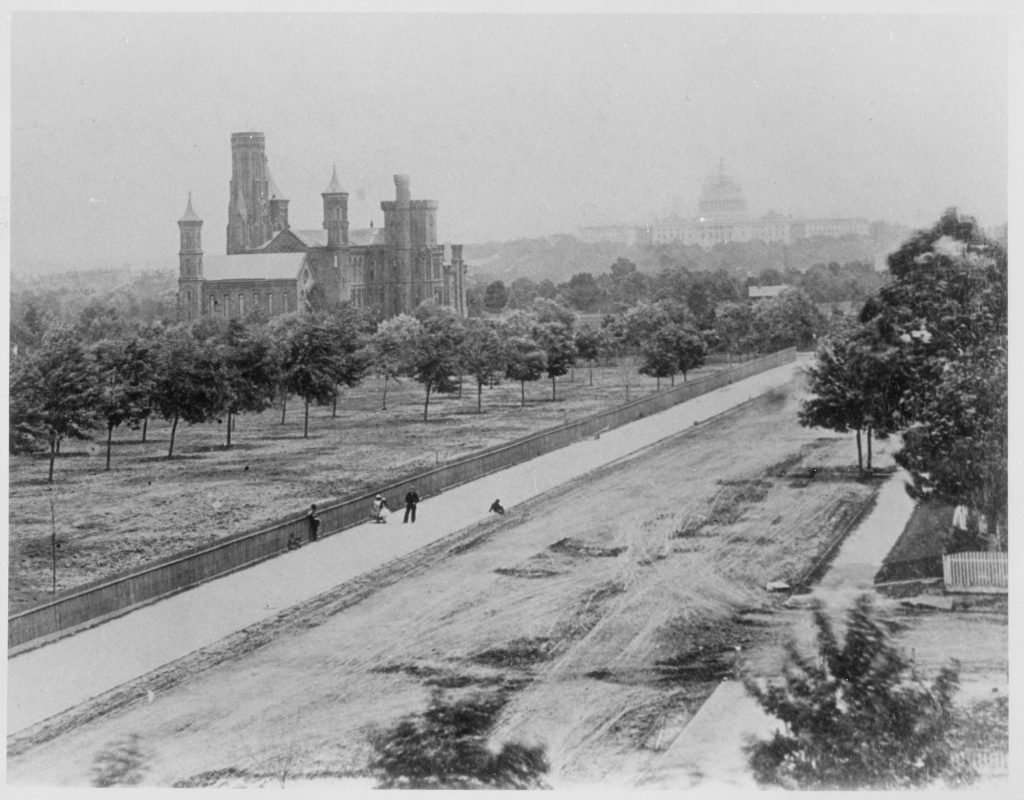

The National Museum of African American History and Culture has in its collections a copy of Twelve Years a Slave: The Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841 and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation near the Red River in Louisiana, published in Auburn, New York, in 1853. A free black man, captured and sold into slavery, Northup recounts being held in a slave pen “within the very shadow of the Capitol.” In its original plain, brown publisher’s cloth binding, water-stained and worn, the volume attests to the power of the book as a cultural artifact. This first-hand testimony of a slave is preserved in a building that stands in the shadow of the Washington Monument. Jails for abducted and runaway slaves and slave auction sites in the new Federal City were once in taverns and along the streets that now surround the National Mall.

Autobiographies of antebellum enslaved people, fugitive or former, are an extensive and influential tradition in American culture. They speak to the country’s founding identity, giving voice to those in bondage and their search for freedom. The genre of enslaved peoples narratives is a distinctive contribution to world literature. They provide testament to individual slaves’ experiences, preserving their memory, even when edited and altered by white abolitionists. The publications are historical records of enslaved peoples’ working lives, food ways, music, folklore, accounts of abuse, of runaways, their experiences on the Underground Railway and in the Civil War, and attempts at gaining literacy.

The writings of enslaved people of the 18th and 19th centuries are an integral part of the American story and their enormous significance was recognized early. In “Narratives of Fugitive Slaves,” an article for the Christian Examiner in 1849, a minister in Boston, Ephraim Peabody, wrote:

Among the most remarkable productions of the age,— remarkable as being pictures of slavery by the slave, remarkable as disclosing under a new light the mixed elements of American civilization, and not less remarkable as a vivid exhibition of the force and working of the native love of freedom in the individual mind.

This psychology of an enslaved person and reaction to violence was expressed in Biblical terms by Frederick Douglass in all three of his autobiographies. He delineates the decisive moment in his life as the fight against a brutal slave-breaker on a Maryland plantation: “I felt as I never felt before. It was glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom.”

The battle with Mr. Covey was the turning-point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood. It inspired me again with a determination to be free … I now resolved that however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed when I could be a slave in fact.

Enslaved peoples narratives have immense value not only in the study of history and genealogical research but also in their literary merits and in the understanding of the failings of moral and political institutions.

Are we, the Smithsonian’s librarians and curators, adequately providing ready access to these original materials in our collections? What are the obstacles to a more complete representation of black literature and corresponding bibliographical records to aid scholarly research? A full review of our holdings and how they are described is not an effortless process. But an appraisal of our work, including how we relate to the Museums’ collections, particularly with African American literature, is of critical importance. Are there biases in our approach to both print and digital texts?

Terminology for searching in our catalog is determined by the Library of Congress Subject Authority Cooperative Program. Earlier cataloging practices did not allow for classification of skin color or race. Using the approved subject, “Slave narratives,” in the Online Public Access Catalog of the Smithsonian Libraries, currently gathers thirty-four titles, only two of which are of the antebellum period. One work is the second autobiography of the great abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (New York, 1855; the gift of Charles A. Beyah). The other books are recent publications, either reprints or scholarly examinations of the literature. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African (London, 1789), cataloged by the Libraries but the property of the National Portrait Gallery, does not have the genre “Slave narrative.” This classic early work (now disputed), which went through several editions, has as its subject “Slaves—Biography.” The Narrative of Solomon Northup, similarly in a museum and not a library, also does not have the access point of “slave narratives.” Two first editions of The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (Boston, 1845) has as subject headings “Slaves’ writings, American” and “African American abolitionists.” “Slaves—Autobiography,” “Slaves—Personal Narratives,” “Blacks in literature,” and “Black authors” are also acceptable terms and can be found in our online catalog.

A reader or librarian interested in the enslaved peoples narratives in the Smithsonian’s collections would have to be well-versed and diligent in searching by all the applicable terms, individual titles, and known authors. While there are many reference works and excellent online projects to consult in this bibliographical undertaking, this would be a scattered and time-consuming approach.

There are other hurdles for the bibliographer and cataloger. In the antebellum period, enslaved peoples narratives were so popular that publishers took notice and produced fictitious accounts. This can complicate research. The legitimacy of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano has been challenged, now thought by some historians to have been written solely by an abolitionist or to be a complete fabrication. Contemporary novels have worth, whether written for altruistic or financial reasons, but should they be included in a list of narratives if not a documentary source?

The controversial novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or, Life Among the Lowly (Boston, 1852), by Harriet Beecher Stowe – to whom Twelve Years a Slave: The Narrative of Solomon Northup is dedicated – was composed in Maine. The novel drew upon, in part, The Life of Josiah Henson (1849). The 1858 Boston edition of that narrative, retitled Father Henson’s Story of his Own Life, containing an introduction by Stowe, is held by the Smithsonian Libraries, as well as the first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (“eightieth thousand printing”). Stowe’ work is said to be the best-selling novel of the 19th century and highly influential in the abolitionist movement. While its main theme is the evilness of slavery, it is sentimental, purporting that Christian love will triumph over all, and the characters are stereotypically drawn. The caricatures are startingly revealed, particularly in the illustrations, in a shortened version, “The People’s Illustrated Edition,” published in London, also in 1852, as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or, Negro Life in the Slave States of America. Reviled for much of the 20th century, Stowe’s book is now being reappraised. One reevaluation is The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin (2006), edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Hollis Robbins.

Stowe’s work appeared first in serial form, in installments of the newspaper The National Era, beginning in 1851. Almost immediately, “anti-Tom novels,” were rushed into print. Aunt Phillis’s Cabin, or, Southern Life as it is, by Mary H. Eastman (Philadelphia, 1852), written to counteract Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is an example of a pro-slavery novel. The author grew up on a plantation in Warrenton, Virginia, and wrote her book while living in nearby Washington, D.C. It depicts a farm run with slave labor as a happy, contented place with all its inhabitants mutually supportive. Enumerating such works by apologists, defending the institution of slavery, illuminates the powerful force of the authentic written narratives, and demonstrates how they were received by those Americans who felt threatened by the enslaved people’s voices and the abolitionist movement.

With any book used as a primary source, the task of the historian or bibliographer is determining when the story first published. Other issues to address are: is it a contemporary first-hand account or a later recollection? What should be included in a bibliography and categorized as slave narratives? The narrative and other writings of William Wells Brown were popular in the period. A fugitive slave, novelist and abolitionist, he penned the first African American military history, The Negro in the American Rebellion, His Heroism and His Fidelity (Boston, 1867). It has much to say on contemporary racial tensions. But would it be added to a Smithsonian bibliography of slave biography?

Narratives of enslaved people, promoted by abolitionists from 1831 and sold at meetings, were often issued in broadside or pamphlet form, cheaply printed and bound. After being circulated, sometimes read over and over, these pieces of ephemera were not meant to be permanent and did not last long. Some titles had multiple reprintings in different editions and issues with variant titles. Textual comparisons need to be investigated, informing how an enslaved person’s narrative might have been reworked for white readers and otherwise transformed. Such analysis can demonstrate how a person’s identity was lost in the reprintings, written for larger North America and European audiences.

Twelve Years a Slave, in the African American Museum, while considered a first edition, is of the “seventeenth thousand printing.” Within two years of its publication in 1853, it had sold 27,000 copies. Slavery in the United States: A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, a Black Man (1836), published by subscription by a Pennsylvania newspaper editor, was later promoted by abolitionists. Following the commercial success of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a New York publisher took advantage and released Ball’s portrait as Fifty Years in Chains, or, The Life of an American Slave. There are two copies of the 1858 edition in Smithsonian Libraries collections and the earlier title is noted in the bibliographical records but not the editorial changes from the initial work. Fifty Years in Chains has lost the author. The publisher declares in the preface: “The subject of the story is still a slave by the laws of this country, and it would not be wise to reveal his name.”

The most famous of the narratives of enslaved people’s genre is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. The publishing history of this title, an evolving record of the abolitionist as one of America’s great thinkers, can largely be traced in the holdings of the Smithsonian Libraries. This widely read slim volume was first published in 1845, at the Anti-slavery Office in Boston. There are two variant copies in the Dibner Library, both in their original brown publisher’s cloth bindings, and they retain the frontispiece portrait of the author. Within four months of its May 1st publication, 5,000 copies had been sold. The National Museum of African American History and Culture Library has an edition of the following year—another indication that the narrative was a powerful force and best-seller. Douglass’ My Bondage, and My Freedom came out in 1855. There are also two copies of this work at the Smithsonian, one in the object collections and the other in the library of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The autobiography was expanded further in 1881, finally revealing the details of his escape to freedom, as The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (the Libraries has the edition of the following year). Three years before his death, the author again revised the title, continually updating with events of the era.

Provenance, or the history of past ownership, is another principal element in our current cataloging. One of the first editions of Douglass’ Narrative was acquired in 1931 by the Smithsonian Institution National Museum (the name for the then main museum of the Institution, located in what is now the National Museum of Natural History), before the Smithsonian Libraries was formally organized. The other has a penciled inscription “Lucy L. Brown / Book / Waterloo Seneca Co / N.Y. 1848.” Such markings can reveal much about who, and where and when, read this title, and inform about the slave narratives’ impact. Carefully recording such evidence, including bookplates, annotations, insertions, and binding descriptions, aids the historical record by informing of the books’ transmission and reception of contemporary readers.

Researchers at the Smithsonian must do additional legwork, apart from the different library branches, in that some enslaved peoples narratives, so significant as material culture objects, are held by the museums. Sometimes titles are in our Libraries’ catalog, but others are more often found only in the online Smithsonian Collections Search Center. As indicated earlier, cataloging practices and rules have changed over time and there are often different local practices, particularly of museum descriptions. In addition to the previously mentioned collection of the National Portrait Gallery and the African American Museum of History and Culture, the National Museum of American History has a truly rare example of this literature, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa: But Resident Above Sixty Years in the United States of America (New London, Connecticut, 1798). Venture, born in Guinea in 1728, was named after the ship he was placed on after being kidnapped and sold for a piece of cloth and four gallons of rum. Venture eventually settled in East Haddam, Connecticut; he dedicated his story to a local school teacher, Elisa Niles. While there is a wonderful description of this copy, complete with its fascinating provenance, there are not any access points in the museum’s record for a researcher of slave narratives if not searching for the specific title and author.

And there are significant titles missing in the Smithsonian’s collections. The classic narrative of Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself (1861) is not represented and would give voice to the female perspective, fraught with issues of sexual abuse and oppression. While available in later anthologies, reprints, and digitized copies, the originals enhance our strengths and help us tell the complete American story. Another title lacking on our shelves is the inspiration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It is the autobiography of a slave who escaped from a tobacco plantation in what is now the Washington suburb of Bethesda, Maryland: The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (Boston, 1849). Its acquisition would be a moving complement to the original autobiography of Frederick Douglass, the great orator, who was enslaved in Maryland and lived the last seventeen years of his life in Washington, where he worked on his final autobiography. There are the horrible events in Twelve Years a Slave: The Narrative of Solomon Northup that took place in this city, the home of the Smithsonian. These local echoes in the narratives underscore how slavery dominated the nation and shaped the capital from its beginnings.

Raising awareness of the documents written by African Americans of life, history and culture in the 18th and 19th centuries speaks to the Libraries’ mission of the increase and diffusion of knowledge. Acquiring, identifying, cataloging, providing access to, and promoting them in the Smithsonian Libraries is a challenge to be undertaken. With limited resources and competing demands in the sprawling complex of museums, research centers, and twenty-one branch libraries, there is much work to be done. But these rich sources of American identity, as well as other under-represented records of the black experience, can be prioritized. A Smithsonian-wide initiative, bringing together digital humanities, enumerative bibliography, and scholarly editing, could underscore their importance by making the texts easily available. A book history approach, including printing history, distribution of and the materiality of the texts, of African American literature is for a more complete understanding of the complexity of slave narratives. These original materials aid the Museums’ and Libraries’ current work and essential goals, preserving them to aid current and future historical research and education.

The former slave Olaudah Equiano wrote in 1789 that “The worth of a soul cannot be told.” But the stories of enslaved individuals can be.

A selection of reference sources in the Smithsonian Libraries to help identify individual narratives of enslaved people:

Preliminary List of Books and Pamphlets by Negro Authors for Paris Exposition and Library of Congress, by Daniel Alexander Payne Murray and Wilberforce Eames (1900).

The Negro Author: His Development in America, by Vernon Loggins, (1931).

Dorothy Porter Wesley, Early American Negro Writings: A Bibliographical Study (1945).

The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography. 12 volume-work edited by George P. Rawick (1977)

To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760-1865 (1986).

Unchained Memories: Readings from the Slave Narratives (2002).

The Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative (2007).

North American Slaves Narratives, Documenting the American South http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/.

This undertaking by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is comprehensive with many of the titles digitized. It includes narratives published as broadsides, pamphlets, or books as well as biographies and some fictionalized accounts in English.

The famous Depression-era Works Project Administration’s oral history has been published in three volumes, Slave Culture: A Documentary Collection of the Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project (Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood, 2014). Most of the original recorded interviews are in the Library of Congress.

Nichols, Charles H. “Who Read the Slave Narratives?” The Phylon Quarterly (volume 20, number 1959), ppages 149-162.

Other studies:

Roy, Michaël. “The Vanishing Slave: Publishing the Narrative of Charles Ball, from Slavery in the United States (1836) to Fifty Years in Chains (1858).” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of American (Volume 111:4, December 2017), pages 513-545.

One Comment

[…] que as suas narrativas fossem publicadas, através do movimento antiescravagista. De modo que, as slave narratives, tornaram-se um importante dispositivo na edificação da memória da resistência negra das […]