How can a magazine show the range and depth of grief? In perhaps the most grievous moment of recent memory, the attacks of September 11th, 2001, the mourning in America rippled from the sites of the tragedies through all kinds of media and into the hearts and minds of citizens of America and the world. Just as the painful words, sounds, and images flowed into the American soul from televisions, radios, and news magazines in the immediate aftermath of the attacks, there were outpourings of personal grief publicized later as people processed the trauma. Publications that are bastions of the multiplicity of our country (magazines, journals, and other periodicals) show how many different groups reacted to 9/11. Fortunately, Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex (SLRA) holds many such publications, even up to very recent issues, so through the materials available here, researchers can encounter America’s most heartfelt reactions in print. Some pronounced their patriotism. Some held special tenderness for the victims. Many rose in defense of what they saw as most American. All tried to find a way through fear for their livelihoods, their passions, and their very lives.

Flag Fever

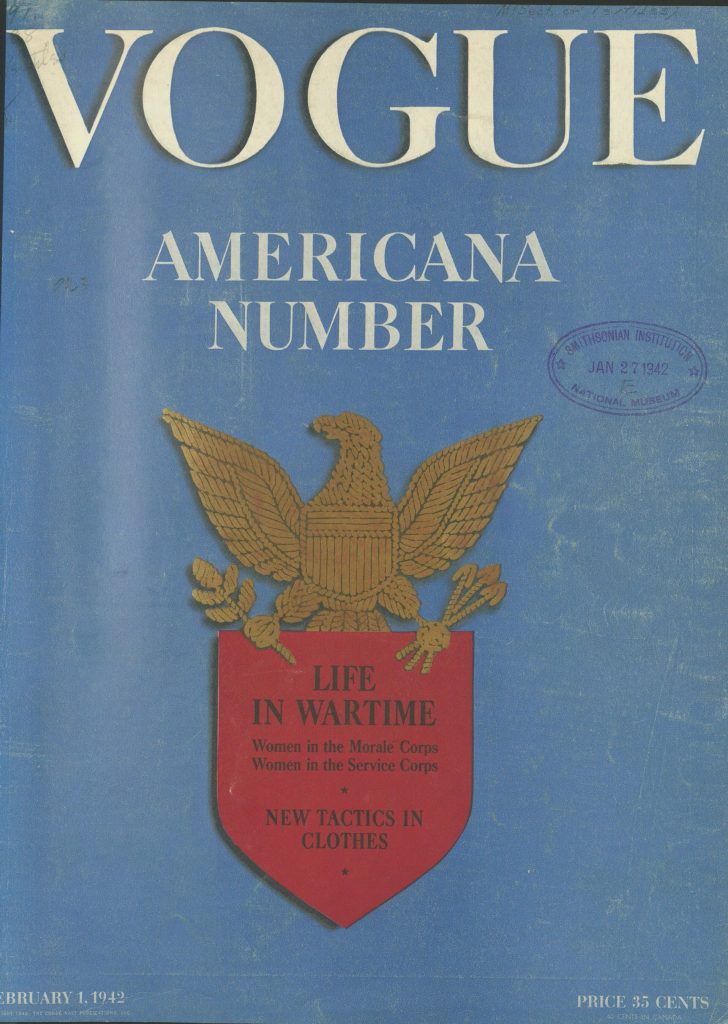

“Flag Fever” was the phrased coined by the New York Times[1] to talk about the sudden surge in patriotic displays following the attacks on September 11. More American flags were more prominently displayed in homes and businesses, and stock phrases like “United We Stand” and “God Bless America” appeared in more places than ever. Periodicals were no exception, from the highest popularity to the deepest niche. Perhaps most obvious is the premier fashion magazine Vogue (pictured above), who despite only mentioning the date of September 11 five times in their 543 page November 2001 issue, revamped their entire color scheme to red, white, and blue. The visual change was both striking and lasting, not disappearing until the following year. This wasn’t the first time Vogue had made a radical color shift in the face of national disaster. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Vogue’s transition to a patriotic palette, though more slowly and stoically, as seen by the 1942 issues below.

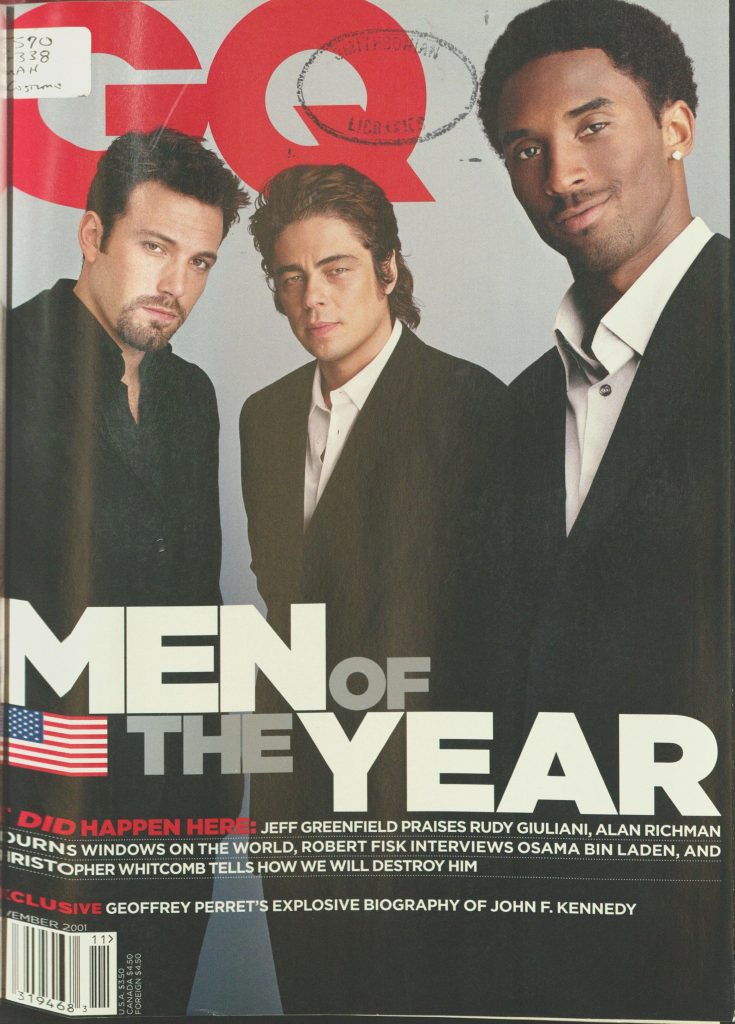

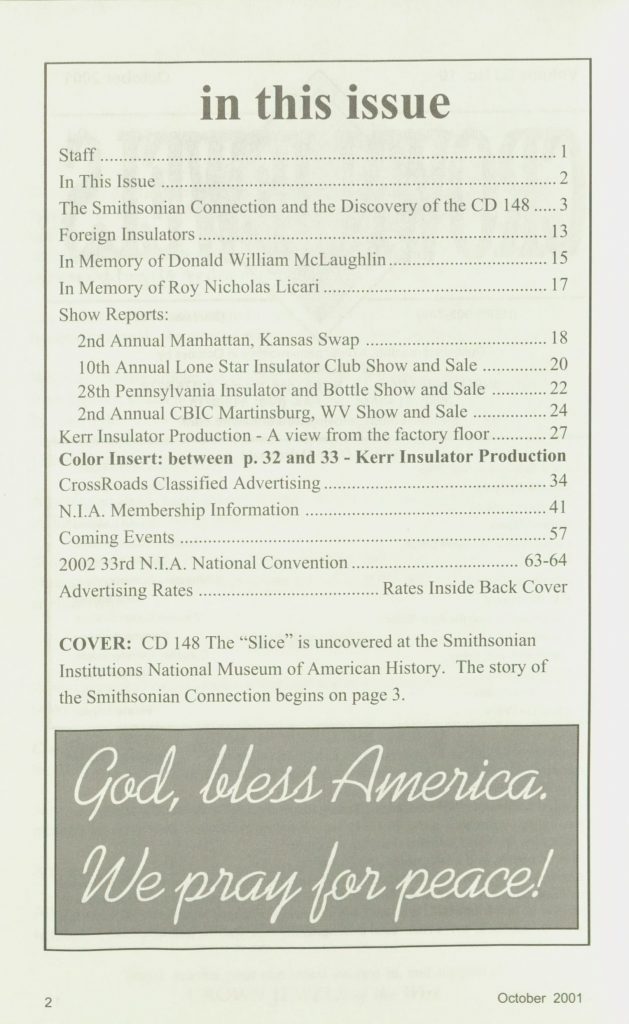

Vogue wasn’t the only magazine to make changes complementing surging patriotism. Flags and patriotic sayings spangled covers and introductory material of periodicals both national and niche. Men’s magazine Gentleman’s Quarterly didn’t change their color palette, but added a flag to their cover, as did many other popular publications. But even journals whose contents did not relate to the cultural impact of 9/11 joined in. Crown Jewels of the Wire may be one of the most hyper-specific periodicals in our collections in its complete devotion to the minutiae of glass insulators on top of telephone poles, but they still showed their support for America in times of tragedy.

Somber Notes

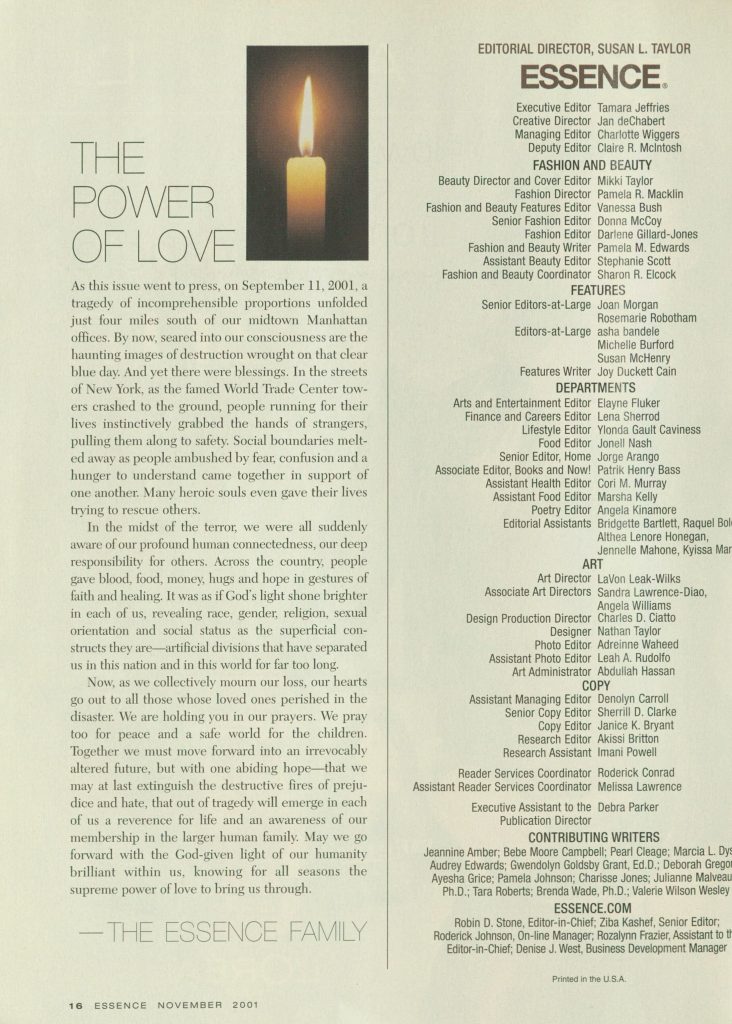

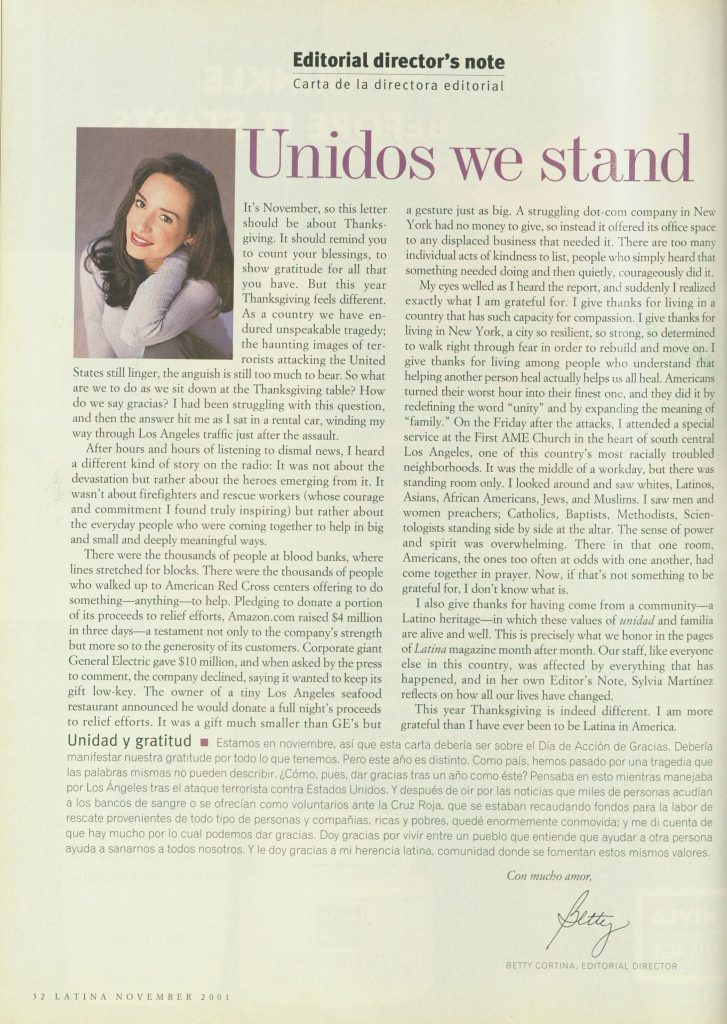

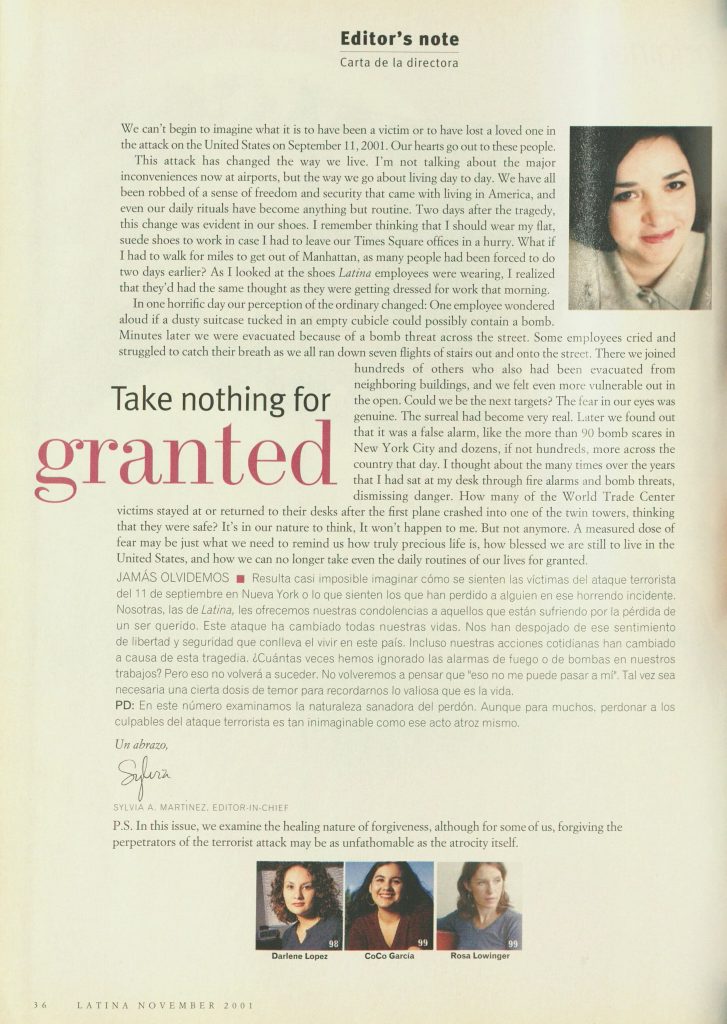

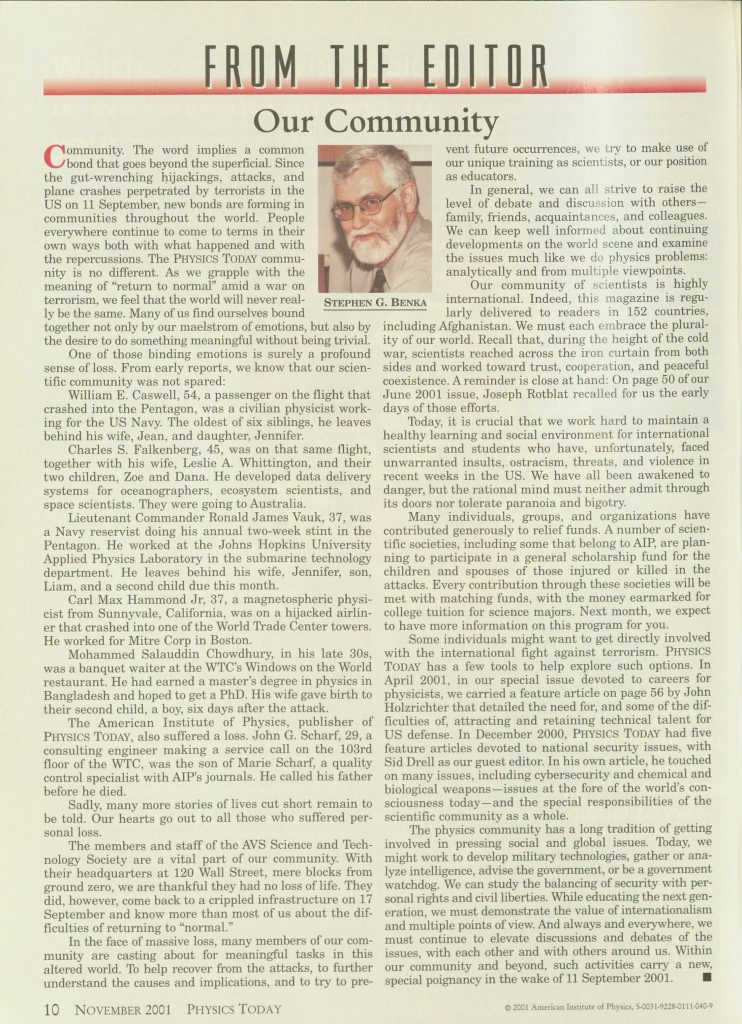

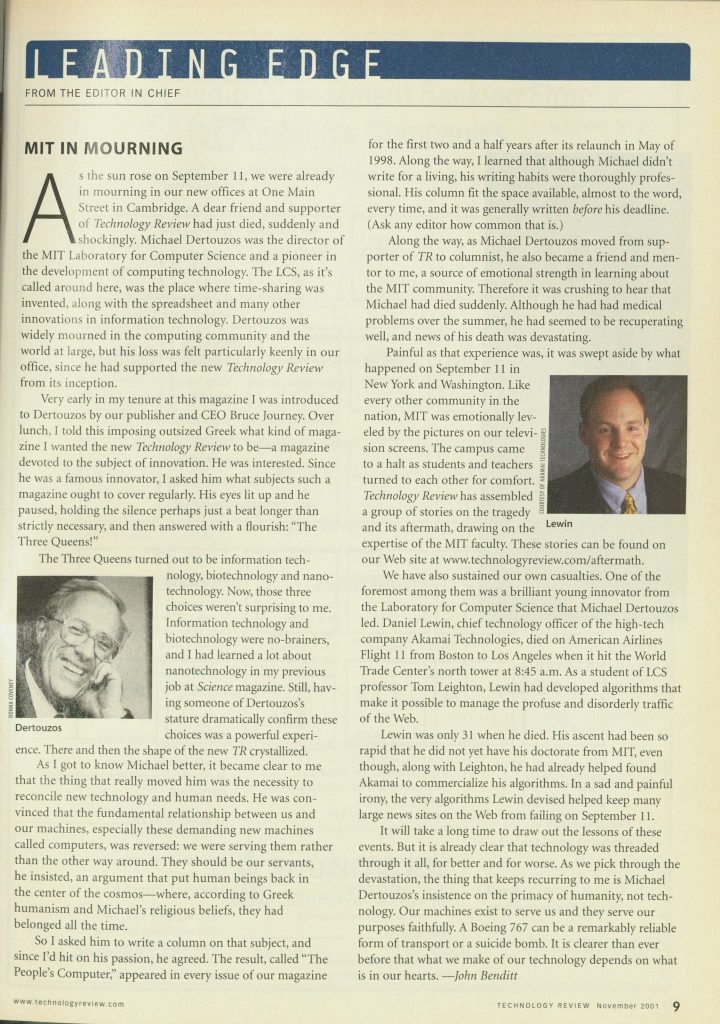

The pace of magazine production, with timelines extending months back to allow for research, editing, illustration and layout, did not allow for many periodicals to adjust their content in response to 9/11. Many October issues of magazines were on newsstands the day of the attack, and November issues were getting their layout finalized for printing. But one element of a magazine, often saved for last, became an outlet for direct and humanizing mourning in the wake of terrorism: the editor’s note.

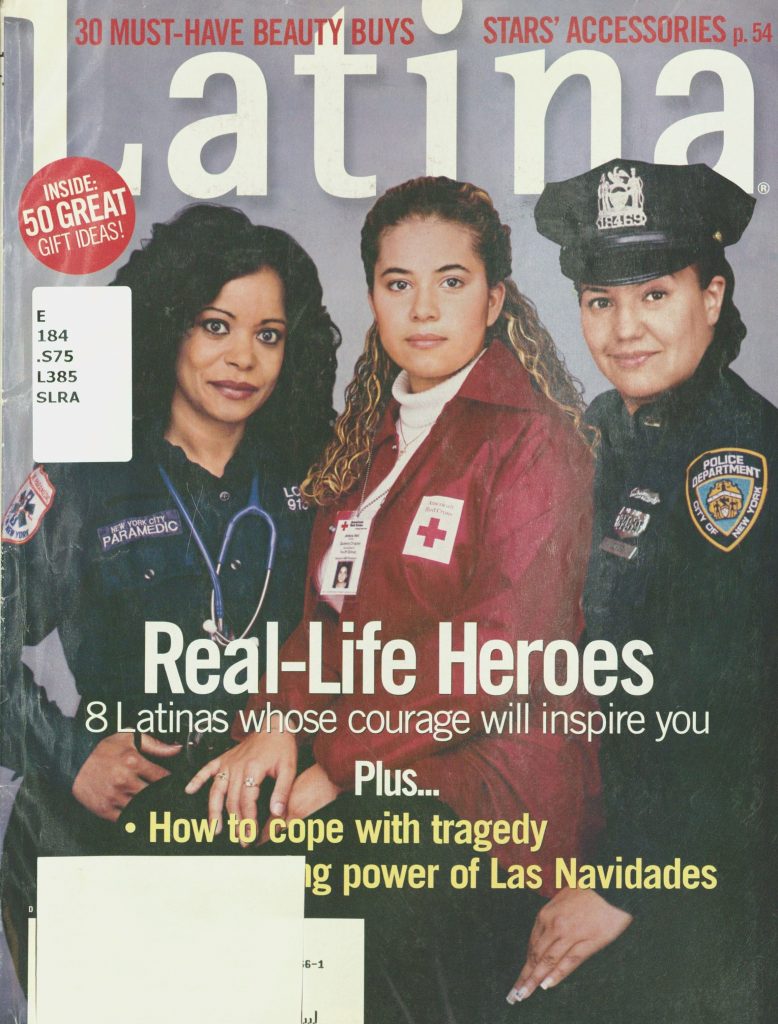

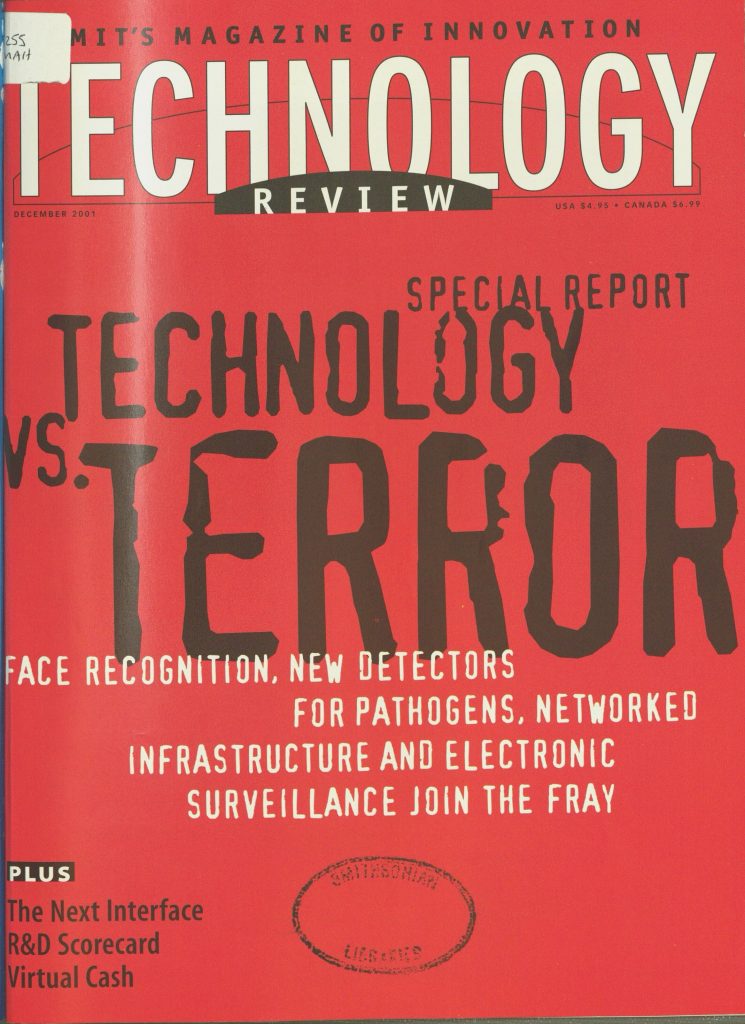

Often, like in the dual notes from Latina magazine pictured above, these open-hearted missives show the personal touches of the pain of the attacks: a boss noticing that her employees are wearing shoes more suited to quick escape than business attire or an editor commenting that terrorism complicates an issue’s theme of forgiveness. Perhaps most gut-wrenching are editor’s notes that have become makeshift obituaries. They memorialize a loss close to a community, once bonded merely by mutual interest, now sealed by grief. These show up in unexpected places, like Physics Today or MIT’s Technology Review.

Forums for Fear

Many people who remember the aftermath of September 11 will recall panics in the following months, motivated by many fears, from anthrax to economic downturn to racial animus. As opposed to the more universal and generalized expressions of patriotism highlighted above, much of the fear-driven content created by magazines was centered on the specialized interests of the publication’s audiences. Some of this coverage has aged better than others. A particularly strong example (above) is Wired magazine, whose issue on cyberwarfare presaged many problems that we are still grappling with, but whose presumptiveness about some social issues like privacy and encryption read as authoritarian today. In an interview with Phil Zimmerman, inventor of an encryption system now apparently not used by the attacks, Wired’s first question was “Are you sorry?”

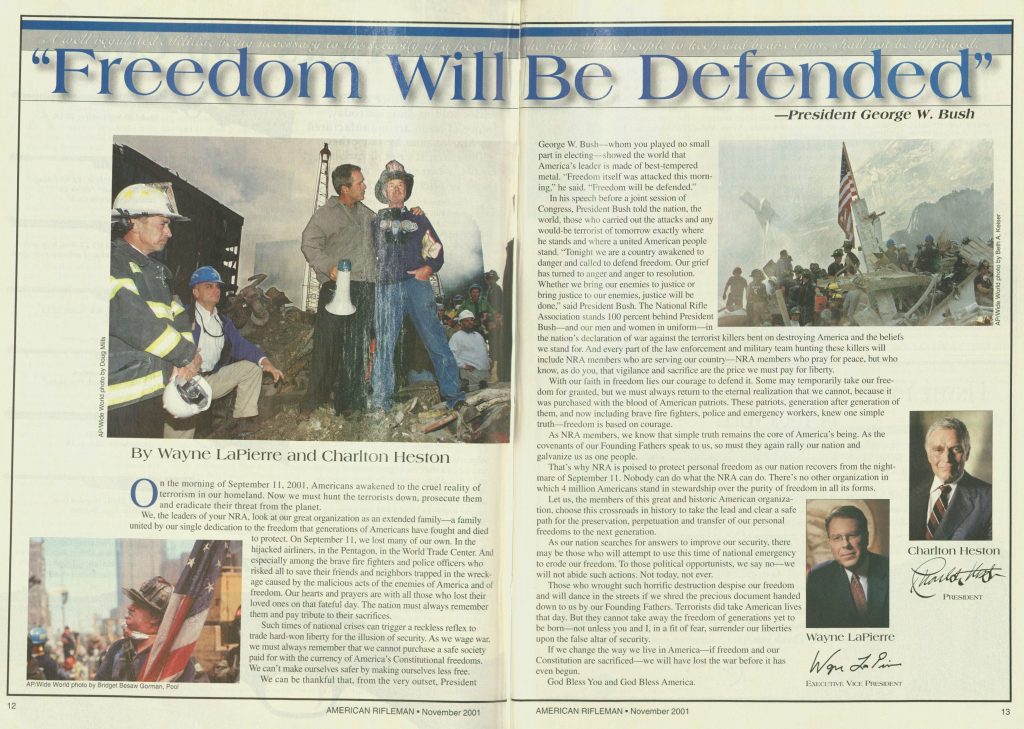

Other fears drove content extended beyond acts of terrorism and defense against them and into the wider societal wake that they left, though no less specific to the concerns of readers. American Rifleman, the official journal of the National Rifle Association, rallied to President George W. Bush’s exhortations to defend freedom by recommitting themselves to what they view as America’s most fundamental freedom: the right to bear arms.

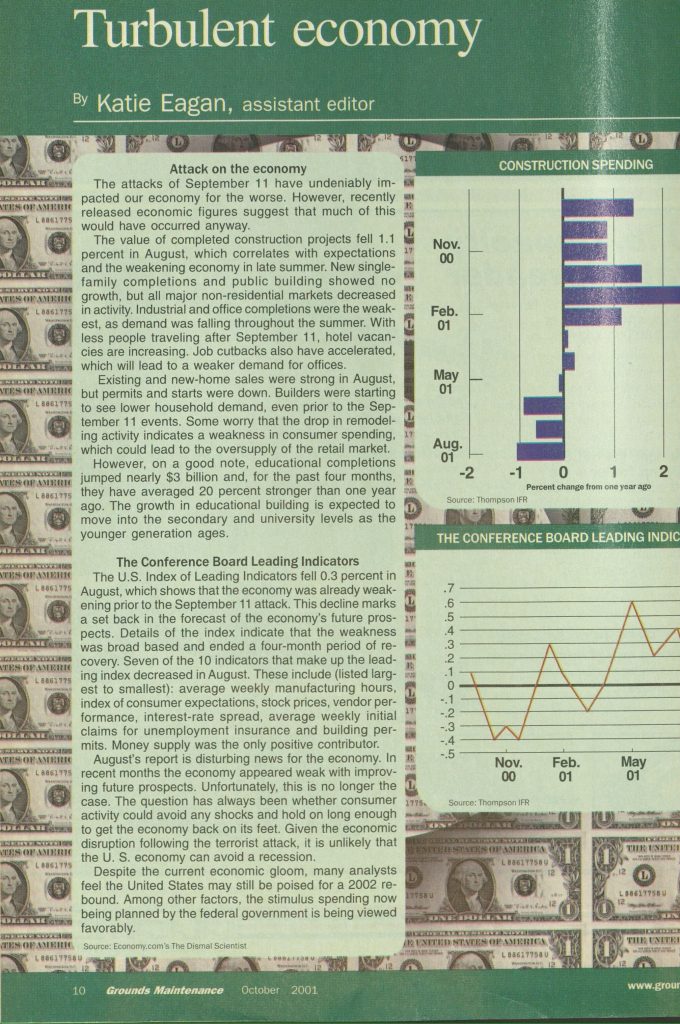

Another group had decidedly practical concern relating to September 11: the fear of recession. This worry was dealt with thoroughly in Grounds Maintenance, a magazine devoted to landscape design, construction, and maintenance. This makes sense for a professional periodical in a price-sensitive industry, but also shows how Americans were seeing 9/11 through their preexisting anxieties, and, as the covers shown below indicate, how 9/11 changed how Americans saw themselves.

[1] Ideas & Trends: Put ‘Em Up; Flag Fever: the Paradox of Patriotism by Blaine Harden, New York Times, Sept. 30, 2001 https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/30/weekinreview/ideas-trends-put-em-up-flag-fever-the-paradox-of-patriotism.html

Be First to Comment