The post below is brought to you by intern Miriam Storm. Miriam interned for the American Art/Portrait Gallery branch library. She has recently completed her Master of Letters in Art History at the University of St Andrews. Despite the time she spent there, she still does not know the first thing about golf but has become an expert on the Royal Family. Interested in our intern or fellowship opportunities? Check out the available positions on our web page!

The Smithsonian American Art Museum/National Portrait Gallery (AA/PG) Library has a dynamic collection of over 150,000 files on artists, art institutions, and collectors. These files generally contain ephemera such as small exhibition brochures, announcements of or invitations to gallery shows, press releases, clippings, and/or reproductions. These files feature both well-known artists as well as ones that never became famous and also include illustrators such as Maxfield Parrish.

Maxfield Parrish was an illustrator of the Golden Age of Illustration and provided America with fanciful images that have enthralled viewers for decades. Parrish worked on illustrations for books written by L. Frank Baum and Kenneth Grahame, for instance, and his works were always well-received. The Smithsonian Libraries has several fine examples of books illustrated by Parrish, including Poems of Childhood by Eugene Field and The Lure of the Garden by Hildegarde Hawthorne.

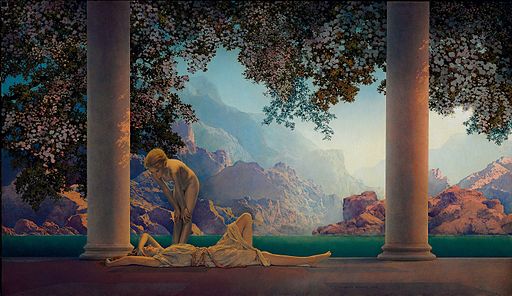

Parrish’s works were met with such immense popularity that in 1925 copies of his painting Daybreak, “could be found in one out of every four American households.”[1] Parrish’s vertical file here at AA/PG gives testament to this—Daybreak is used on two different exhibition announcements found in the file and other works were reproduced widely. Why does Parrish’s work continue to enchant audiences?

Maxfield Parrish. Daybreak. 1922. Oil on panel. 67.3 x 114 cm. Private Collection. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Maxfield Parrish. Daybreak. 1922. Oil on panel. 67.3 x 114 cm. Private Collection. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Most of Parrish’s work was specifically created for the illustration of books and commercial use. These two categories were historically thought by academic audiences to lack any deeper intentions or significance. Art created only to amuse or to sell was not usually considered as ‘fine art.’ Parrish’s works, which were both illustrative and commercial, traditionally were of little interest to the “fine art” world. Organizations such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art wondered how to make these distinctions and Parrish’s offered up his own thoughts on the separation between “fine” art and that of illustrations:

“…Why should not all such things, illustrations, decorations, miniatures, etc., be looked upon as pictures? …If they are good of their kind they are good as pictures. The Museum [The Metropolitan Museum of Art] has on its walls many pictures which are purely illustrative and nothing else. …Why not judge all these things by one standard? …It seems to me the original purpose of the work has precious little to do with the subject.”[2]

For several decades Parrish’s work suffered from this stigma, however, galleries and museums began to display his works more consistently from the late 1960s onwards, as seen by the numerous exhibition announcements found in the vertical files. The persistent nature of his work was being recognized.

This persistence comes from other-worldly qualities of his works that provide the framework for our imaginations take flight. Parrish’s work holds back the assumed narrative of the image just enough that it demands the viewer create their own. When asked to tell the story behind Daybreak, Parrish replied, “I know full well the public wants a story …but to my mind if a picture does not tell its own story, it’s better to have the story without the picture …The picture tells all there is, there is nothing more.”[3]

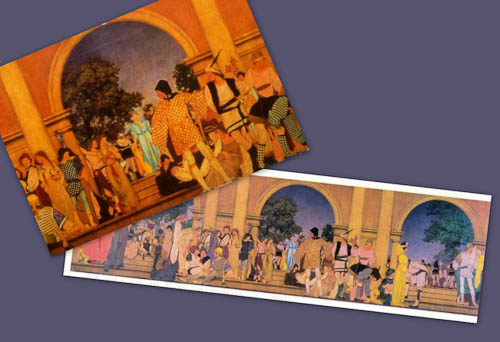

Instead of providing the viewer with a story, Parrish has created an elusive narrative. The mural Parrish created for Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s North Wall of 1918, fills the viewer with many questions about an apparent narrative- where are they? Why are they assembled? However, no answers are provided. Something is happening but we are not sure what or why. The beauty of this image is sufficient but the responses it evokes are on par with that of ‘fine art.’ Surely a work that stimulates thoughts and questions in the mind of the viewer is valuable criteria for scholarship.

Maxfield Parrish. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s North Wall Mural.

Maxfield Parrish. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s North Wall Mural.

1918. Oil on Canvas. 5 ft. x 18.5 ft. (featured on two different exhibition announcements in the vertical files)

Parrish creates captivating and dream-like worlds. It is that elusiveness that enthralls the viewer and defies traditional scholarship as it cannot be easily dissected. Simply because Parrish used his talents for commercial illustration should not discredit him in any way. His work presented an elusive narrative that persistently placed his work in the public eye and more recently in the realm of serious scholarship and will undoubtedly continue to do so for years to come.

Are you curious to know what kind of scholarship there is on Maxfield Parrish? Check out the books in the bibliography as well as Parrish’s vertical file for articles, exhibit announcements and much more! Other artists from the Golden Age of Illustration can also be found in the AAPG vertical files including Howard Pyle, Edward Penfield, and Charles Dana Gibson (creator of the Gibson Girl).

The following books on Parrish can all be found in the AAPG Library:

Maxfield Parrish by Coy Ludwig.

America’s Great Illustrators by Susan E. Meyer.

Maxfield Parrish 1870-1966 by Sylvia Yount.

[1] Sylvia Yount, Maxfield Parrish 1870-1966 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1999), 15.

[2] “Should Museums Form Collections of Illustrations?” New York Herald, 1 December 1907 as quoted in Sylvia Yount, Maxfield Parrish 1870-1966 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.), 59.

[3] Yount, Maxfield Parrish 1870-1966, 102.

3 Comments

The Pied Piper Bar in the Palace Hotel in San Francisco is a favorite gathering place for local librarians and archivists, in part due to the fantastic and large painting that graces the bar (and proximity to local transit). I think there’s a similar painting in Manhattan (likewise in a bar). The next time you are in town, join us for a special viewing of public art!

[…] as well as interesting articles about current materials and artists. From “Maxfield Parrish — An Elusive Narrative“: Maxfield Parrish was an illustrator of the Golden Age of Illustration and provided America […]

Their is a fantastic article out of the UK with unknown and new game-changing information about pop culture artist, Maxfield Parrish and filmmaker, George Lucas. This is dramatic and fantastic info, must read it, it is on a genius site, this is epic, enjoy the knowledge. Look it up on,

(The Game of Nerds; origins of Star War the case for Maxfield Parrish ).

This is historic information and common logic dictates that this story should be shared all around the world.