Like books, quilts are symbolic items with patterns that can tell stories. Quilts tell domestic narratives and have been recognized as important historical artifacts. As a result, the Smithsonian’s National Quilt Collection at the National Museum of American History contains hundreds of quilts. However, it might be surprising to hear that the Smithsonian Libraries also hold quilts – or rather, quilt-like books.

Like books, quilts are symbolic items with patterns that can tell stories. Quilts tell domestic narratives and have been recognized as important historical artifacts. As a result, the Smithsonian’s National Quilt Collection at the National Museum of American History contains hundreds of quilts. However, it might be surprising to hear that the Smithsonian Libraries also hold quilts – or rather, quilt-like books.

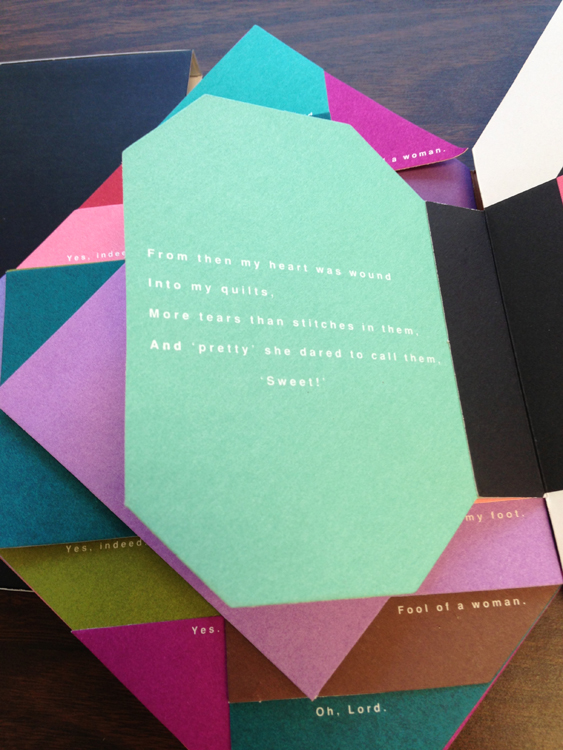

Aunt Sallie’s Lament, at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum Library, turns the pages of a poem into a quilt. The Quilts of Gee’s Bend Vol. 2, recently acquired by the library of the Smithsonian American Art Museum/National Portrait Gallery, wordlessly explores the forms and patterns of quilts from rural Alabama. These two works at the Smithsonian libraries push the boundary between quilt and book, craft and art, image and text.

In Aunt Sallie’s Lament, a dealer arrives from the city, “searching the backroads ‘for Americana.’” She finds Aunt Sallie’s quilts and dares to call them “pretty” and “sweet.” Sallie, angered by this intrusion and presumption, explains her history to the reader in verse: As a young woman, she fell for Jake Turner, a patent medicine man who gave Sallie “a taste of the world / Outside my gate.” She finds that “when he left town,” he “plain spoiled my taste / For what I might have had.” No longer content with her country life, she channels her dissatisfaction into her quilts. To hear them called “pretty” and “sweet” by the dealer, years later, dismisses her personal history and leaves her frustrated. Her story is stitched into the quilts’ fabric, legible in the patterns – if only the city dealer knew how to read it.

Designed by Claire Van Vliet and written by Margaret Kaufman, Aunt Sallie’s Lament is an artists’ book. This story about quilting is constructed in a book form that looks like a diamond quilt. Originally published in a limited edition by Janus Press in 1988, Aunt Sallie’s Lament is also available in a trade edition, published by Chronicle Books in 1993. The trade edition, pictured above, can be viewed at Cooper-Hewitt. As the reader moves through the book, the turning pages compose a quilt-like visual pattern.

Like Aunt Sallie, the quilters of Gee’s Bend, a small, primarily African American community in Alabama, have caught the eye of dealers, artists, and curators from the city. With large, undulating, geometric blocks of color, their quilts more closely resemble 20th century abstract art than the more precise and figural patchwork characteristic of domestic quilts. In the late 90s, collectors and curators began to acquire quilts by Gee’s Bend artists. Since the 2000s, several exhibits have displayed these quilts to large audiences and critical acclaim.

The abstract, geometric playfulness of Gee’s Bend quilts is translated into book form by the artist Carolyn Shattuck. Her The Quilts of Gee’s Bend, Vol. 2 takes images of colorful fabric and reconstitutes them in a moveable book structure. The flexagon binding can be rearranged into different shapes by the reader. The triangles of the structure recall the diamonds and other geometric patterns of quilts. Though The Quilts of Gee’s Bend doesn’t have any text, the work still alludes to the work of Gee’s Bend artists and the story of how their quilts became popular in the contemporary museum world.

Quilts, the critic Mara Witzling argues, have their own language – a special way of communicating without words.[1] Patterns, fabric, construction, and visual symbolism combine to create meanings for the viewer. Though books traditionally transmit meaning through text, Aunt Sallie’s Lament and The Quilts of Gee’s Bend convey significance through binding, form, patterns, colors, and movement. These artists’ books use innovative forms to involve the reader. Their physical structures stitch together books and quilts, creating a language beyond text.

– Michelle Strizever

Michelle Strizever is a curation specialist in Washington DC. She received her MLS from the University of Maryland and her PhD in English from the University of Pennsylvania. In 2012, she served as a Smithsonian Institution Libraries Professional Development Intern for artists’ books.

[1] Mara Witzling, “Quilt Language: Towards a Poetics of Quilting,” Women’s History Review 18.4 (2009): 619-637.

One Comment

Quilts, no matter what form they take, can tell a wonderful story about the place in life that the creator is at. Many use quilting as an opportunity to release some of the stresses or losses in their life. I love your comments on the quilted books in the article.