The conservation of special collections materials is rarely a straightforward endeavor. It’s important to treat each item as a unique object, and to let its particular history and condition drive the decision-making process. Often, the path forward is only revealed once treatment begins, as the conservator becomes more and more familiar with the book, sometimes through research and analysis, but often simply by observing and handling the book over a period of time.

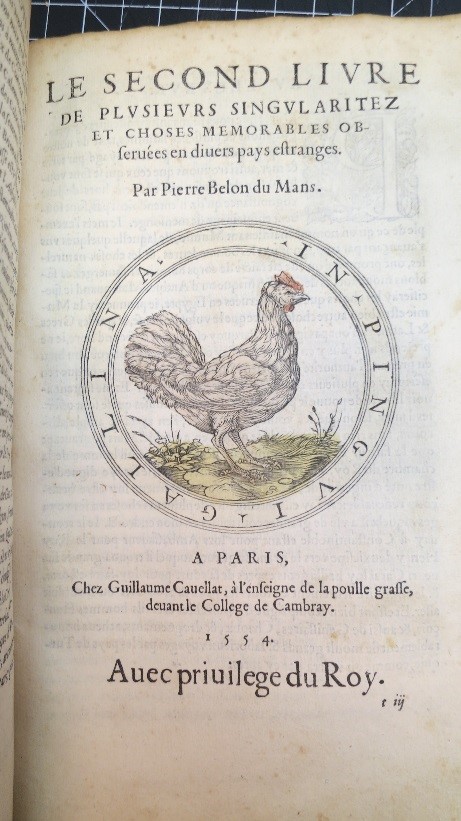

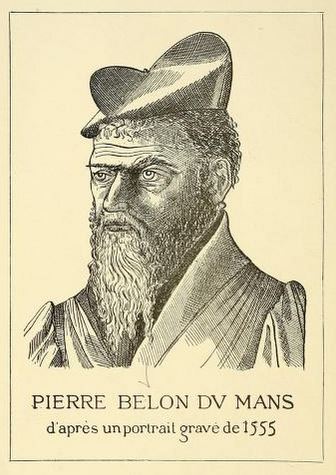

Recently, I have been treating a book that was adopted for preservation from the Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History, Les observations de plusieurs singularitez et choses memorables trouvées en Grèce, Asie, Judée, Egypte, Arabie et autres pays étrangèrs, by Pierre Belon (1517-1564), published in 1554.

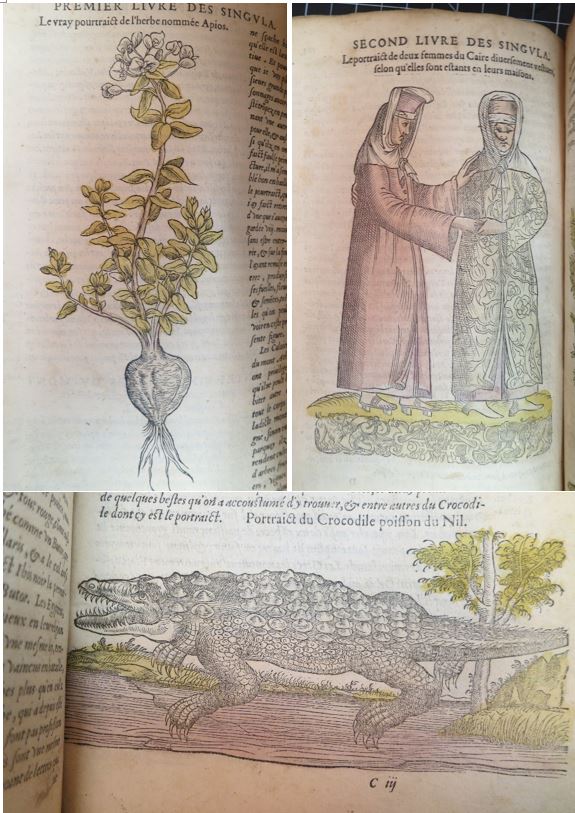

Belon, originally trained as an apothecary, was a French naturalist, and the work describes his travels in the eastern Mediterranean in the years 1546-48. He records, in words and woodcut illustrations, numerous animals and plants, many never before seen by Western readers, as well as the customs and culture of the peoples he encountered. This work, as well as others by Belon, remained popular well into the 17th century.

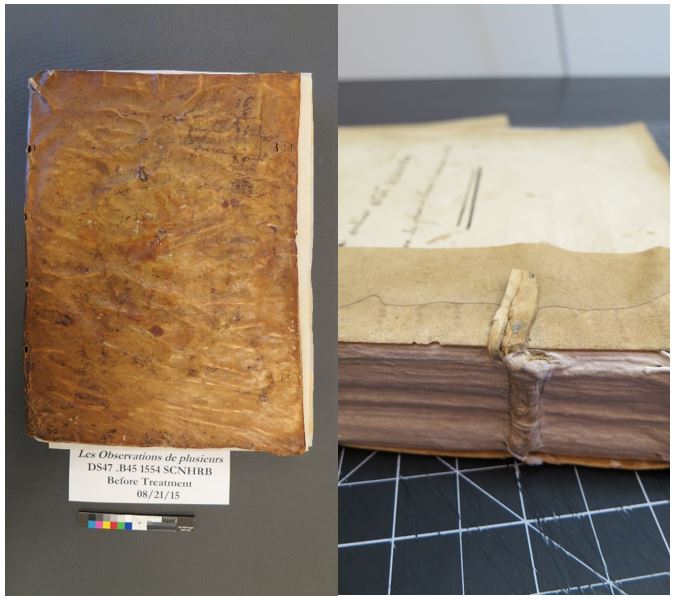

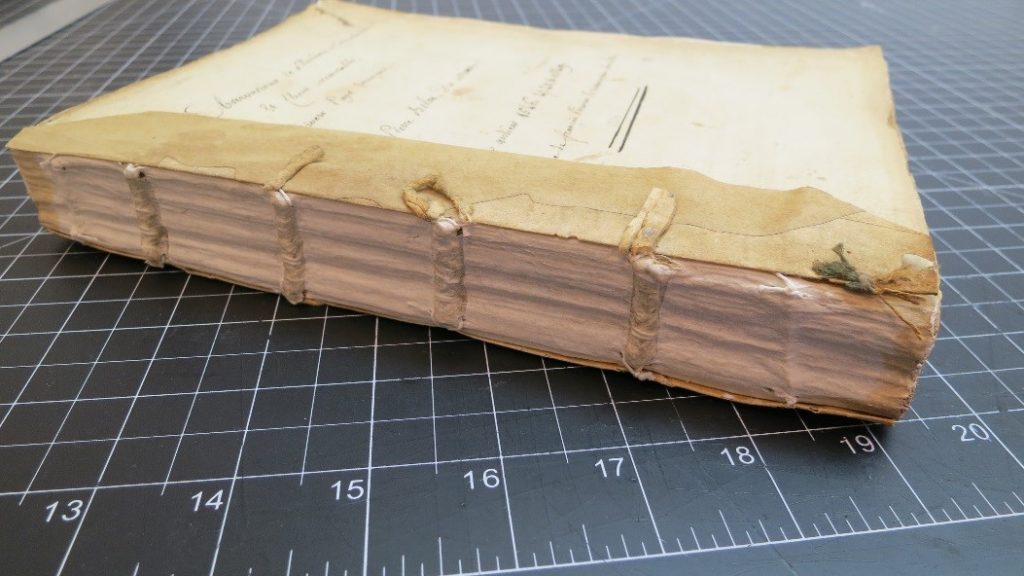

Printed in Paris, Les observations retains its original binding, a structure commonly referred to as “limp vellum”*. It has no rigid covers, but is simply constructed from a single piece of animal skin parchment, which has been skillfully cut and folded to accurately fit the book. This style of binding encompasses a wide range of subtle variation in form and design, from the very plain to the highly decorated, and harkens back to earlier, medieval bindings associated with ledgers and other archival structures. It was extremely popular throughout Europe for several hundred years beginning in the early 16th century, probably owing to its durability and relatively quick construction. Both of these aspects are in part attributable to the lack of adhesive used; the binding is attached to the text simply by lacing the sewing support slips through holes or slits that have been pierced in the parchment. Perhaps because of their often humble appearance however, these bindings have not often survived into the present day; historically, wealthy buyers may have wished to furnish their books with more expensive bindings, and modern-day collectors and institutions have tended to prefer bindings with rigid covers.

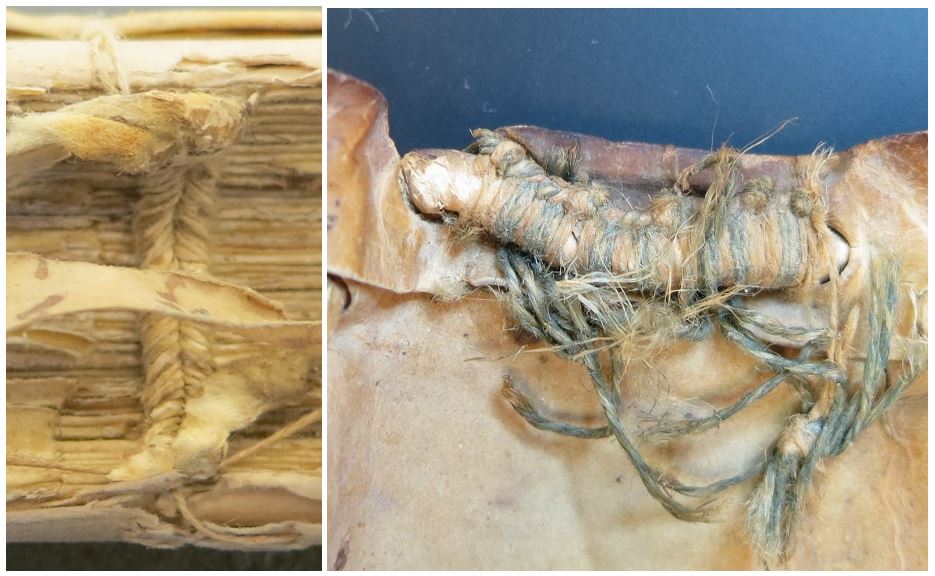

The binding on our copy of Les observations could accurately be described as vellum; it is a smooth, heavyweight calfskin that originally would have been a golden yellow. The book was sewn on four split alum-tawed leather supports with a herringbone stitch, and had 2-color primary silk endbands; if you aren’t familiar with this terminology, these are all indications of a book which was sewn without many compromises in terms of quality, and therefore time and expense. It is this level of craftsmanship which has allowed it to survive in its original condition for so long.

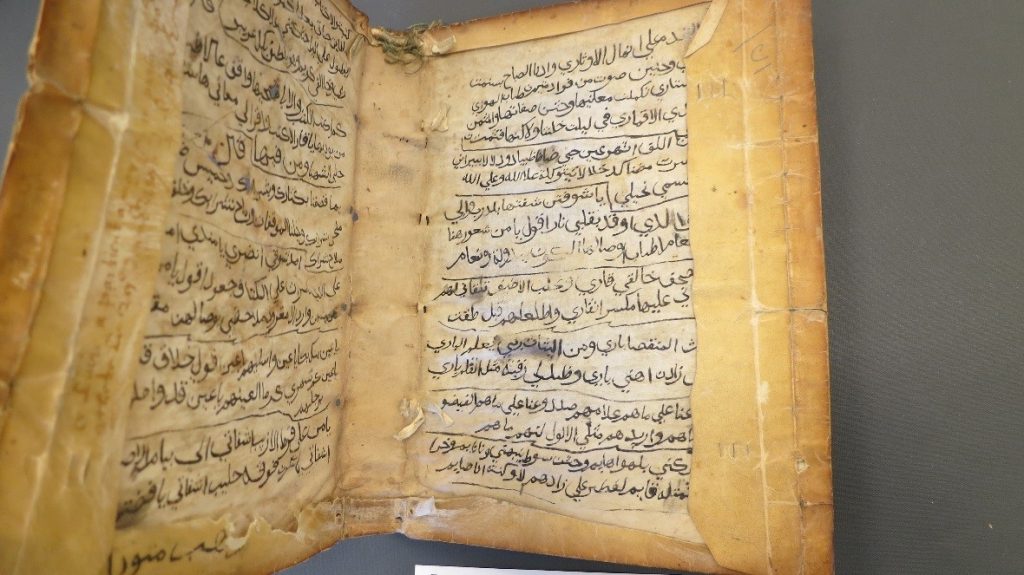

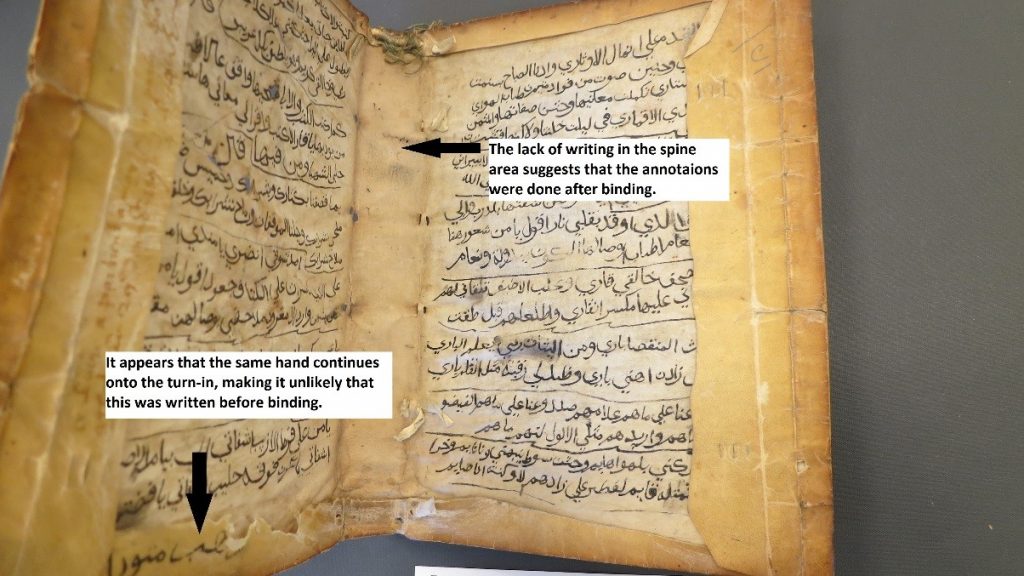

This copy has an additional, completely unique, feature: the inside of both sides of the cover are filled with Arabic handwriting in black ink, which the adoption catalogue describes as an instance of recycling old manuscript waste (a common practice among bookbinders).

When it arrived in the Book Conservation Lab, Les observations presented a number of preservation concerns. The book had become completely separated from its binding, owing principally to breaks in the sewing support slips. The sewing structure itself appeared weak in several places, with some sections loose from breaks in the sewing thread. There was some damage to the paper, especially at the beginning and end of the text, and the title page (not original to the text, but a later, handwritten copy) had been previously repaired with a now brittle tissue.

At first glance, an obvious direction for treatment might be to take the book apart completely, re-sew and rebind it in a new binding, saving the original for future reference. As I examined the book more closely, however, I came to feel that the sewing structure was not only largely intact, but actually robust, and worth preserving. I also observed that the Arabic script on the inside cover was not recycled manuscript waste, but was clearly written sometime after the book was bound. This is important because while manuscript waste in bindings generally bears no relation to the text (except when trying to relate place of printing to place of binding), annotations made after binding can help scholars track readers’ response to the text, as well as provide evidence of provenance. Hopefully someone will translate these annotations one day!

These observations, which only came to me after spending considerable time examining the book and its binding, led me to a more conservative approach to treatment. Instead of removing the original sewing, I repaired the damage by re-sewing the loose sections with lengths of new linen thread. I gently re-shaped the spine and reinforced my repairs with new spine linings of a medium-weight Japanese paper. Finally, I reattached the parchment cover to the book, using lengths of new parchment, laced through the book and the original holes of the cover. This will prevent the annotations becoming separated from the book. As with many treatment methodologies aimed at special collections materials, this more conservative approach ended up requiring more time and skill than simply disbinding and rebinding, but this flexibility helps ensure that objects receive the quality of care befitting their historic status.

*though some scholars in the field point out the imprecision of this term, since vellum technically refers to finer quality calfskin parchment only

(see http://www.ligatus.org.uk/lob/search?search_api_views_fulltext=vellum)

2 Comments

The handwriting looks quite clear. It’s been far too long since I’ve studied Arabic, but maybe if you post clear images of both pages, crowdsourcing could translate it pretty easily for you.

Great idea, Bret! Thanks for the suggestion.

Erin Rushing

Outreach Librarian