My normal week is satisfyingly hectic: offering trainings to colleagues at the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park (NZP), hopping on the Metro, providing reference support at the National Museum of Natural History’s (NMNH) main library, retrieving references for Mineral Sciences staff, and on Fridays, traveling 160 miles (round trip) to Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) in Front Royal, VA. Add on committee meetings, literature searches, Association of Zoos & Aquarium bibliographies, and long-term projects, and it seems there is never enough time in a work week. And I love it.

Since being home, I have been just as busy, but in a much different way. I still meet with colleagues (virtually), provide reference support, and run literature searches, but I’ve also been able to complete my to-do list and make real progress on long-term projects. I was already an old hand at teleworking, which has served me well since mid-May, when I joined the Smithsonian’s COVID-19 Reopening Task Force (RTF) on the kind recommendation of an SI colleague.

But what does a zoo librarian know about public health? I’m glad you asked.

Before coming to the Smithsonian, I:

- taught scientific database research to undergraduate and graduate students

- Biology, Environmental Science, Kinesiology, Microbiology, and Zoology

- ran comprehensive literature reviews and occupational health systematic reviews while stationed at federal libraries

- sat ex officio on a university’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)

- created EndNote libraries with 50,000+ unique citations on subjects ranging from occupation lifting and pregnancy to the carcinogenic properties of asphalt sealant

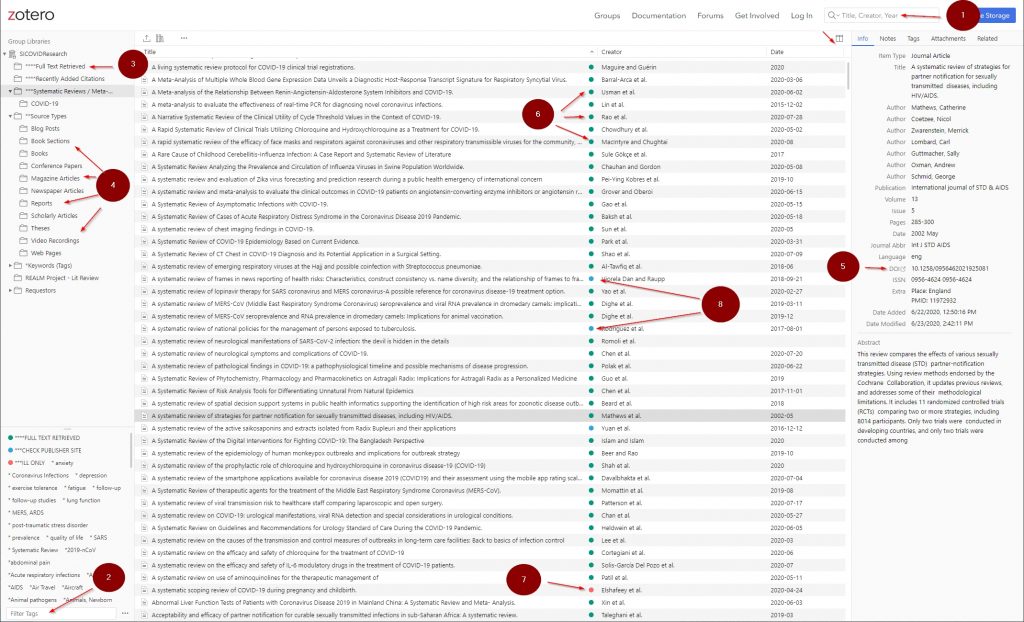

To assist the important work of my colleagues on the RTF, I did what I know best…created a citation database. I chose to build it in Zotero, an open source citation manager, which I extensively use to provide research support for SI colleagues and external organizations.

My goal for the COVID-19 citation database is simple: a one-stop repository of all SI accessible scholarly citations and curated (select) newspaper articles, video recordings, and websites. Reducing redundant efforts and increasing efficiency is the best way I know to provide support to my patrons, whether at NZP, NMNH, or SI in general.

- Main search box

- Tag search box

- Articles with full-text retrieved (SI staff only)

- Source Types

- Digital Object Identifiers (DOI) – permalinks to article full-text PDFs on publisher’s sites

- Articles that have had their full-text PDFs retrieved (SI staff only)

- Articles that require publisher site access for full-text retrieval (possible paywall)

- Articles that require interlibrary loan requests for full-text retrieval (SI staff only)

Methodology:

To create the baseline for literature, I utilized the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Browser, as well as the search string used by Battelle for the OCLC/Institute of Museum and Library Services Reopening Archives, Libraries and Museums (OCLC/IMLS REALM) literature review, and created the following search string:

(“COVID-19” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR coronavir* OR hcov)

I did not use any other search terms, in order to retrieve the maximum number of potentially relevant citations.

I retrieved results in Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed, Elsevier’s Scopus, and Google Scholar. To identify burgeoning research, business reactions, and government assessments, I created a Google News Alert.

Maintenance:

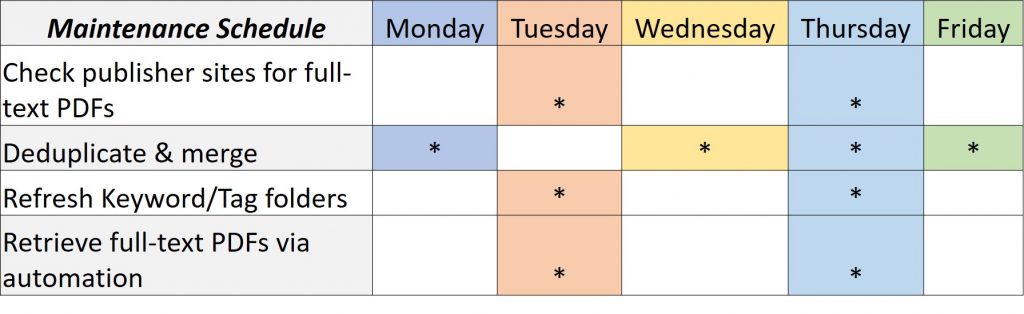

Citation databases do not always export full records (even if the option is selected). In order to create complete records, I deduplicated nearly 40,000 results, making sure that (when possible) each citation had at least a title, author(s), date of publication, publication title, volume, issue, pages, and an abstract. Since COVID-19 literature has almost totally been written in 2020, most citations include DOIs. Additionally, many citations appear in databases during the pre-print stage, meaning they are often incomplete, so it is important to deduplicate/merge across multiple databases to create complete references.

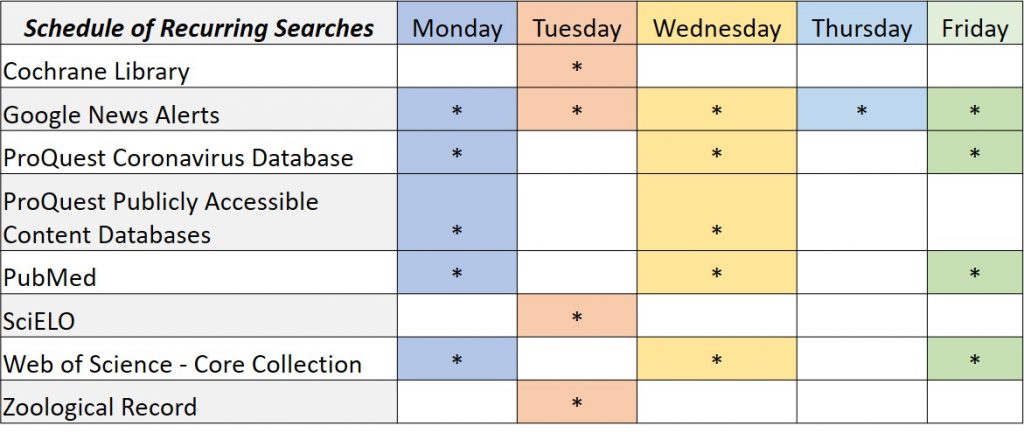

A database of this size requires a lot of discipline and can take over one’s life. I have created schedules for recurring searches (1) and maintenance (2) so I can have time to respond to patron requests.

I have since added more sources, and in addition to the aforementioned databases, I also run recurring searches in Cochrane Library, ProQuest Coronavirus Database and Publicly Available Content Databases, SciELO, and Zoological Record.

To date, I have reviewed 167,250 citations, adding an average of 950 new citations per day.

Use:

The online version of the Zotero database has two search boxes (including the ability to search just the tags). Since the online version does not reflect saved search folders created in the desktop version, I have created numerous keyword folders and manually update them every few days. Examples of delimiters include Source Types, Locations, Pathology, and Cleaning.

Users are able to highlight specific articles or even an entire folder and export the results as a bibliography with abstracts, making skimming to locate relevant sources much easier (CTRL-F is your friend).

Points of Interest:

I run searches every business day and base the frequency of searching on the refresh rate of a database (PubMed is run daily; ProQuest is run every few days). Each database has limits on the number of citations that can be exported (e.g., Web of Science – 500 at a time) or per day (ProQuest – 10,000). ProQuest includes keywords as notes, so I have set up automated searches so I can quickly find and delete these data hogs (that, coincidentally, just mirror information in the citation proper).

Print journalism is added regardless of the author’s perceived or overt bias. Once the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, I hope the database will serve SI’s historians well.

Going Live:

Since the database’s initial release , I have used it to create reports on mask and social distancing compliance for the NZP and the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center; face mask efficacy based on type (e.g., N95, KN95, cloth, etc.); air monitoring in office spaces; surface wipe sampling of different types of materials (e.g., steel, plastic, wood); temporal patterns in viral loads; and contact tracing.

Because COVID-19 research is relatively new, I also run pertinent searches on ancillary topics as they pertain to previous outbreaks (e.g., sanitization of surfaces for the elimination of viruses).

I have also created derivative databases for other groups. Currently, I’m providing reference and citation database training and support to the SI group tasked with creating risk assessment models.

If scientia potentia est, then surely convenient access to orderly data is just as important. Supporting researchers is one of the things Smithsonian Libraries does best. If my efforts make the work of my SI colleagues any easier, I’ve done my job.

One Comment

This is awesome, Stephen!