Last year, the Smithsonian began a partnership with Gale, part of Cengage Learning, to digitize content, package it, and make it available through libraries around the world. Gale debuted the first of these products with digital versions of the Smithsonian magazine and Air & Space magazine’s archive. The Smithsonian Libraries is excited to be a part of the second group of products, Smithsonian Collections Online: World’s Fairs & Expositions: Visions Of Tomorrow and Smithsonian Collections Online: Trade Literature & The Merchandising of Industry. Assessment of the items and scanning is already well underway. Get an inside look at what goes on behind the scenes with William Bennett, contract conservator for the project!

My name is William Bennett and I am a contract book conservator currently working at the Smithsonian Book Conservation Lab, hired by Gale, a part of Cengage Learning, to assist with a digitization project underway at the moment. Last September I completed my master’s degree in conservation at West Dean College, located in the south of England, where I specialized in the conservation of books and library materials.

Drawing on the Smithsonian’s collections, Gale is scanning materials from a wide variety of sources, including items from the World’s Fair collections, and before they can be digitized they are reviewed by conservators, including me, to ensure that the items in question can stand up to the rigors of the scanning process. The books and pamphlets are selected for scanning, earmarked for conservation treatment so they can be scanned or, in few instances, they are rejected. Materials may be rejected if they are exceptionally fragile or if there is a better copy of the same item available to scan.

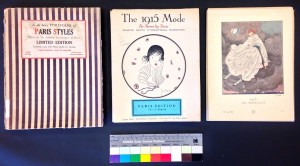

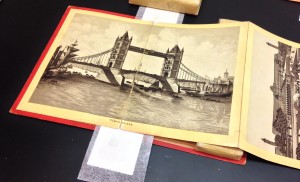

This project is drawing initially from five sources: collections from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Library in New York City; from the National Museum of American History Archives Center; from the American History Library’s body of trade literature, both bound and unbound; and from the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology. Scanning operations have commenced with two of the collections—the trade literature the Smithsonian possesses here in Washington, DC, and the World’s Fair collections from the Cooper-Hewitt Library. The trade literature covers a variety of industries—the majority of which has so far dealt with heavy machinery, but also includes catalogs of pre-fabricated homes from the early twentieth-century, some of which are in color, and all of which are charming. The Cooper-Hewitt World’s Fair items are naturally fascinating, and run the gamut from specialty tourist guides with hotel and restaurant recommendations to official maps of attractions and displays to souvenir booklets and photo albums. The materials also draw from a variety of celebrations, including the London Great Exhibition of 1851, the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, the Paris Expositions Universelles of 1889 and 1900, and the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, to name a few.

Due to the large volume of materials being reviewed and scanned, treatment options are limited and chosen accordingly. Much of the trade literature consists of stapled-pamphlet catalogs, and these frequently have abraded spinefolds, leaving covers split in half and detached, and the staples are often rusted and disintegrating. These require removing the staples, repairing the broken spinefolds with Japanese paper and wheat starch paste, and securing the whole with pamphlet stitching.

The World’s Fair material is incredibly varied, not just in content but in structure. The collectors’ items tend to be of superior quality and have maintained their integrity, whereas some of the souvenir items are printed on embrittled paper and quite literally falling apart at the seams. These are frequently not up to the tasks they were designed for, like this souvenir booklet (see photos below) from the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, printed on an accordion fold pasted to the inside of a folder. The heavy paper the photographs are printed in was not up to the folding and unfolding necessary and split along the folds as a consequence, requiring reinforcement or reattachment with Japanese paper and wheat starch paste.

Once materials have been reviewed and treated if necessary, they are digitized by one of the team of scanners. Depending on the structure of the material, they are scanned on one of two types of machine: one, the Kirtas, designed specifically to accommodate bound volumes, with a cradle holding the book open at an acceptable angle so images can be captured by high-resolution cameras positioned above. The Kirtas also has a pneumatic feature that allows pages to be turned by suction, which works well with modern, strong materials but is not in use with this project. Flat material is scanned on Minolta machines that have a central portion of the scanning platform that can adjust to accommodate spines of scrapbooks or other flat-opening volumes, in addition to flat materials like pamphlets and catalogs. At full capacity and under ideal conditions, scanners on the Kirtas can complete over 12,000 pages a day. Much of the Smithsonian material being scanned, however, requires special handling due to large formats or brittle and fragile conditions, which slows the process somewhat.

The collections currently being digitized form an irreplaceable snapshot of an important period of cultural history. The benefit of this scanning is two-fold: first, digitization is a method of preservation in and of itself, creating a digital version that is not subject to the same deterioration as the physical object; second, where access to tangible items may be limited by handling concerns or distance, the digital version is an excellent substitute.

Once scanning is complete, the data will be processed and eventually made available as part of Gale e-learning offerings, as well as made use of by the Smithsonian. It’s exciting to think that these unique primary source documents may be a focal point of a future classroom or research experience.

5 Comments

I hope the costs to access these scanned databases of material owned by the American public will not be at Gale’s normal exorbitant rates, which are far out of the reach of private researchers with no academic affiliation.

Hi Bill,

Thanks for your comment. An additional benefit of this partnership is that the Smithsonian Libraries will receive scans of all of our material. At some point, the scans will be available through our digital library, free to the public.

Erin Rushing

Digital Images Librarian

Thanks, Erin, that’s very good news. I’ve always had tremendous support from the Smithsonian directly on research projects, particularly from the Dibner Library, and I’m pleased to learn that this project will extend those resources.

Bill Burns

[…] more about the work being done for these collections on Smithsonian’s […]

[…] Note: This post originally appeared on the Smithsonian Libraries’ blog and has been re-posted here, featuring revisions geared towards the West Dean blog audience, with […]