Rhubarb, that harbinger of spring for many, is honored in the United States on January 23rd with National Rhubarb Day. Having let National Rhubarb Vodka Day (first Saturday in December) pass without note, I wanted to bake a pie in preparation. Thanks to the generosity of a neighbor and his bountiful garden last spring and summer, I had plenty set by. Rhubarb does freeze well. Inspired by the scholars transcribing, as well as cooking with and blogging about, culinary manuscripts dating from 1600 to 1800 in the University of Pennsylvania collections (recently profiled in The Washington Post), I turned to the Smithsonian Libraries for my commemorative effort.

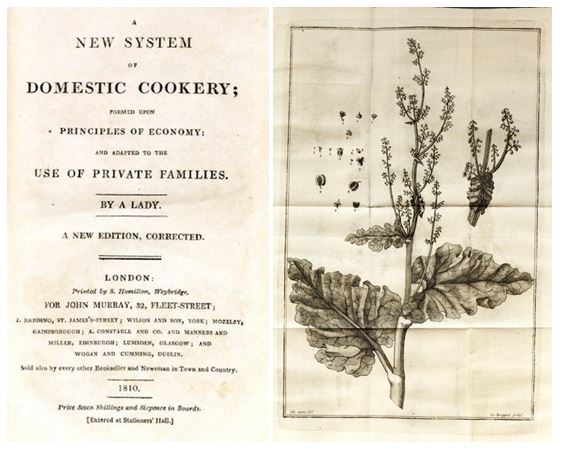

According to some sources (such as Alan Davidson’s The Oxford Companion to Food), the first recipe for rhubarb appears in A New System of Domestic Cookery by Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell (1745-1828), published in 1806. There is a photocopy of a second Boston edition of 1807 in the library of the National Museum of American History but the 1810 London imprint is part of the personal library of the Smithsonian’s original benefactor, James Smithson, now in the vault of the Cullman Library of Natural History. Smithson’s books, numbering only 126 titles, are the few tangible remains of his legacy, survivors of the fire that swept through the Smithsonian’s “Castle” 150 years ago on a bitterly cold day of January 24th.

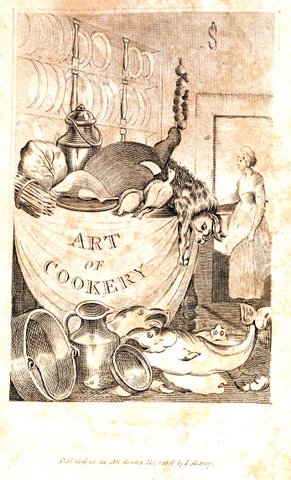

Like most of the books in Smithson’s library, A New System of Domestic Cookery is in its original boards (TX717 .R94 1810). But unlike his copy of Hannah Glass’s Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy (London, 1770; TX705 .G54 1770), which contains manuscript notes, there is no evidence that Domestic Cookery was used in the Smithson household. Indeed, one bolt of leaves is unopened, never hand-slit with a paper-knife by its owner. Now largely unheralded, Mrs. Rundell was the bestselling cookbook author of the first half of the 19th century, with this title having an extraordinary sixty-five editions. A widow in Bath, she initially compiled the recipes, including medicinal ones, for her daughters. The second edition eliminated many of the errors that the feisty author blamed on the printer and the publisher, John Murray, an old family friend, who never did properly pay her for the work.

Also in the Cullman Library is a dissertation of 1752 that had been presided over by the great Swedish naturalist, Carl von Linné, more familiarly known as Linnaeus: Samuel Ziervogel’s Dissertatio Medico Botanica, Sistens Rhabarbarum (RS165.R48 Z54 1752). This thesis on rhubarb, in Latin, emphasizes its therapeutic uses. It is divided into thirteen sections and includes a brief bibliography, noting the effectiveness of the plant in treating diarrhea and dysentery. Linnaeus, whose Species Plantarum (1753) first introduced a consistent use of binomial names for species, had rhubarb (genus Rheum) in the Uppsala Academic Garden, where the plant was listed in another dissertation by student Samuel Nauclér.

The delightful Through the Fields with Linnaeus: a Chapter in Swedish History by Mrs. Florence Caddy (London, 1887), recounts a hungry day when “Though he missed the rhubarb stewed with tapioca and served with whipped cream of his own home, he was an old traveler and could do without delicacies.” And, further along:

Linnaeus stopped at Kongelf, or Konghall, a small town at the foot of the hill by the castle of Bohus. The curate here had rhubarb in his garden—it is curious to think how late in the day rhubarb became common in England, seeing that in Sweden, even in this out-of-the-way place, they cultivated it one hundred years before we took kindly to it (v. 2, p. 189).

Culinary history is a fascinating—if tricky—field of study, as is the plant trade (such as tracing rhubarb’s journey along the Silk Road to the Western World) and declaring any “firsts” is hardly straightforward. But even that French culinary bible Larousse Gastronomique credits the English with introducing rhubarb to the kitchen.

Rhubarb is an herbaceous perennial that became a food staple only in relatively recent history. The plant was highly valued for medical purposes, its roots applied for various ailments. The ancient Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides described rhubarb and its physic properties in his De Materia Medica (written between 50 and 70 AD). There are several editions of this herbal in the Smithsonian Libraries, the earliest is of 1499 (qRS153 .D59 1499 SCDIRB). However, native to northern Asia, rhubarb’s medicinal use goes back long before Dioscorides. Marco Polo remarked about the quality of the plant in his travels in China in 1271 and how merchants traded the precious commodity around all parts of the world.

James Mounsey, as physician to the Czar of Russia, brought rhubarb seeds to Sir Alexander Dick, President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. He grew them with great care and success and The Society of Arts presented him in 1774 with a gold medal “for the best specimen of rhubarb.” Another London physician, Sir William Fordyce, published in 1792 perhaps the first English book on rhubarb: The Great Importance and Proper Method of Cultivating and Curing Rhubarb in Britain for Medical Uses. But throughout the 17th-century, there were scattered recordings of it in botanic gardens in Great Britain. Musaeum Tradescantianum, or, A Collection of Rarities Preserved at South-Lambeth neer London of 1656 (QH70.G7 T76 1656 SCNHRB) lists “Rhabarbarum verum, ‘true Rubarbe.’” The Tradescants, John the elder and his son, John the younger, were great gardeners and plant collectors and this is a catalog of the collection that eventually was presented to Oxford University, forming the core of the Ashmolean Museum.

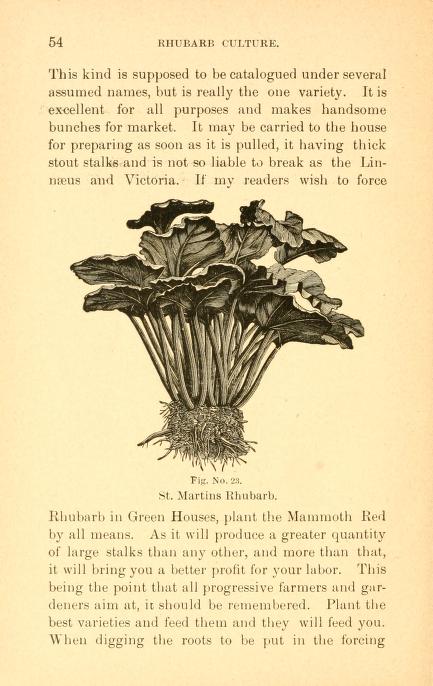

Rhubarb remained a very expensive commodity until just about the time of publication of Mrs. Rundell’s cookery book. Varieties had been developed for culinary purposes and adapted to European soils and climate, specifically R. undulatum, the Siberian rhubarb. Not incidentally, this was a time when the price of sugar came down enough to make it affordable to most households to use the large quantity called for in cooking rhubarb. A nurseryman in South London, Joseph Myatt, promoted it in produce markets in 1808 or 1809 while it was still largely unknown according to the very informed and thorough, Rhubarb: the Wondrous Drug by Clifford M. Foust (Princeton, N.J., 1992; RS165.R48 F68 1992 Botany).

On this side of the Atlantic, as noted by Professor Foust and Joel Fry, Curator of Bartram’s Garden, John Bartram (1699-1777) was the first to have grown it. Correspondence reveals that Bartram, the great botanist and naturalist, received seeds of two varieties from his fellow Quaker Peter Collinson in the 1730s. The Londoner Collinson wrote in a letter to his Pennsylvanian penfriend on September 22, 1739, that both the Siberian and Rhapontick rhubarb “make excellent tarts before most other Fruits fitt for that purpose are ripe” and included his own recipe for rhubarb tart. Still later, in 1770, Benjamin Franklin sent Bartram from London seeds of the “true rhubarb.” Franklin, along with an unnamed “Maine farmer” are the ones often credited with introducing rhubarb to America. By the 1820s, the plant was appearing in New England markets and seed catalogs. Still, our Mrs. Rundell was a remarkably early adopter of rhubarb, to include it in her A New System of Domestic Cookery. The Boston editions of this title helped establish a vogue for this plant in America.

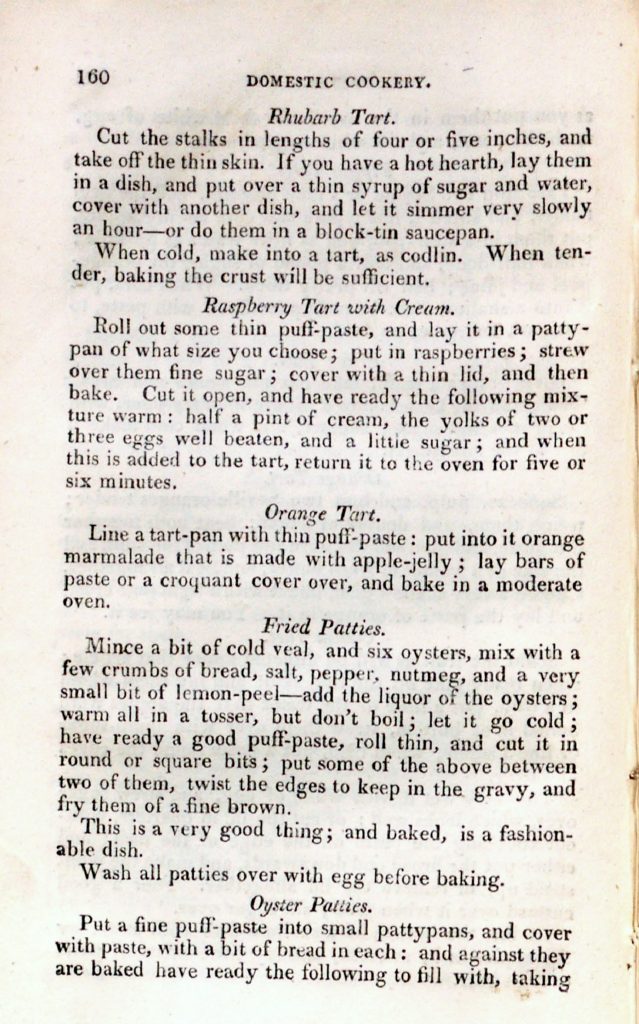

Because stored apples—one of Collinson’s “other Fruits”—had shriveled or gone rotten by spring, rhubarb was soon enormously popular in pie making (so favored for baking that it was commonly called “pie plant”) in both Great Britain and the United States, although this hardy perennial is actually a vegetable. Or was until 1947 when the U.S. Customs Court of Buffalo, New York, ruled that rhubarb was a fruit (for tariff reasons of course). While Collinson believed the pie or tart ”eats best cold” I like mine warm, with whipped cream (a nod to Linnaeus). So I will celebrate this January, and think of the Mrs. Rundell, the Widow of Bath, who ended up late in life in Lausanne, Switzerland, and the peripatetic scientist James Smithson, and wonder if they ever met in the wealthy English ex-pat community there. It is possible. In honor of them both:

Rundell-Smithson Rhubarb Tart

Historical authenticity isn’t everything so this is an adaption of the original recipe. For one, rhubarb, now long cultivated for tenderness, would be jam if cooked on the stove top for an hour. So rather than cooking the rhubarb before placing it in a pie shell, I made a type of sauce (the “syrup” above), to incorporate with the raw slices for some texture and crunch in the finished product. I also added in orange flavor for zing and to commemorate the classic American strawberry-rhubarb pie (its National Day is June 9th), strawberry jam is used.

Take your favorite flaky pie crust or pâte brisée recipe, and line it in a nine-inch tart pan with removable bottom. Partially bake the crust in a 375-degree oven for ten to fifteen minutes. Combine in a stainless steel bowl about one pound of sliced rhubarb, 1/2 cup of sugar (depending on your taste and the rhubarb’s sweetness), a pinch of salt, and 3 tablespoons of flour. Let this mixture stand at room temperature for at least a half-hour till the rhubarb releases its juices. Carefully strain into a small saucepan with 1/3 cup of strawberry jam and equal amount of orange juice or liqueur (I used Grand Mariner; as Julia Child would have said, not necessary but it makes it very nice). Bring these liquids to a slight boil and stir as it thickens. Carefully pour over the rhubarb slices and toss gently. Place in the partially baked shell and return to a 400° oven about twenty to thirty minutes until nice and bubbly.

I sprinkled cinnamon sugar over the finished tart, inspired by a recipe from The Inn at Little Washington. This step can be skipped but cinnamon, which also has its medicinal uses and was traded along the Silk Route, is a nice complement.

Happy baking through the winter!

3 Comments

Excellent read. Wish I had seen this just a few weeks ago when I was making a rhubarb crisp and was curious about the cultivation and history of rhubarb. This endeavor inspired a heated debate regarding whether or not to peel the rhubarb. The crisp was delicious, but your pie sounds better.

I just found this–just a couple of years late! I love rhubarb (I have a rhubarb cookbook coming out in the spring) and enjoyed this historical tour. I cannot for the life of me figure out why we would celebrate rhubarb in January, however.

I love rhubarb, but I am puzzled as to why you even included “Rundell” in the name of your recipe. Your recipe bears no resemblance to that in Rundell’s cookbook, other than they both contain rhubarb and sugar, and they are both pies.

Sorry, but I am both a picky editor and a cookbook collector. I have seen many recipes and cookbooks that claim to have links with ancient or antique recipes, bygone eras, etc., and this type of thing really irks me.

P.S. Your recipe sounds like it would yield an excellent result, much better than the result if one followed Rundell’s recipe.