Beautifully produced but small, the cookbook Home at the Range with George Rector packs a lot of material culture in its 140 pages. Anything but stuffy, this culinary artifact of 1939 evokes America trying to shake off its Depression-era hardships. It reveals a longing for European sophistication while evoking New York City in the livelier era before Prohibition. It displays the development of consumer interest more in style than a recipe. Home at the Range is an example of early 20th-century trends in cookbooks: celebrity, product or appliance manual, niche, gift, haute cuisine, or luxury. And then there is the author as name brand, long before that became a common commodity.

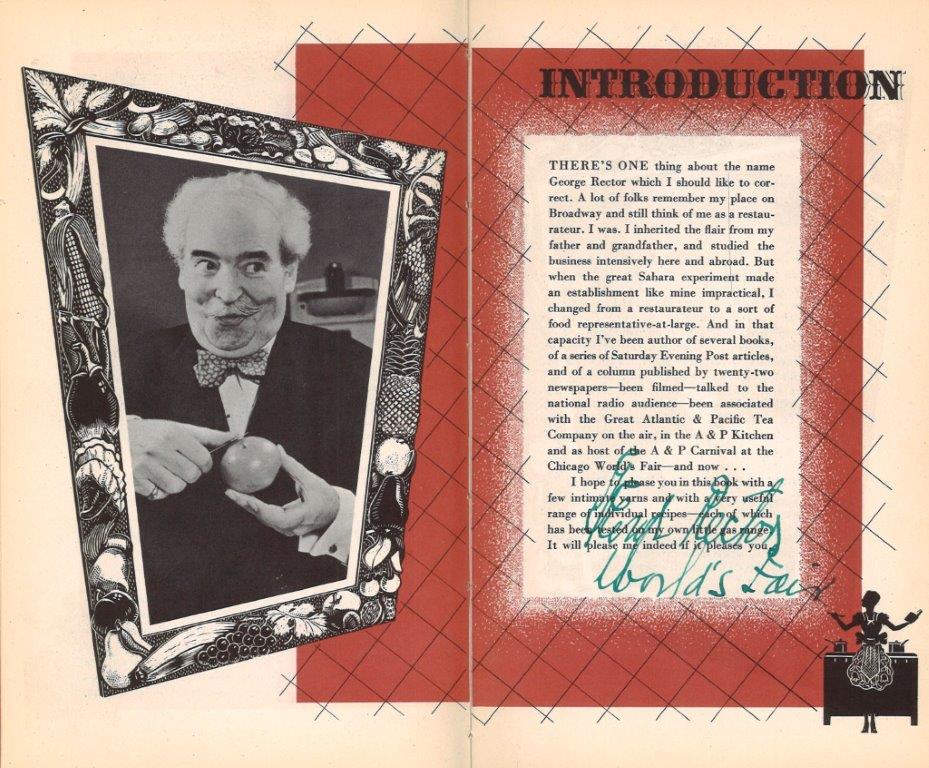

Who was George Rector (1878-1947), then? Opening the covers of Home at the Range, the reader encounters his initials in a bold design on the endpapers. By way of introduction, the author recalls his family’s establishment on Broadway and informs he is no longer a restaurateur, but now “a sort of food representative-at-large. And in that capacity I’ve been author of several books, of a series of Saturday Evening Post articles, and of a column published by twenty-two newspapers—been filmed—talked to the national radio audience—been associated with the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company on the air, in the A & P Kitchen and as host of the A & P Carnival at the Chicago World’s Fair.” In 1928, Rector became the “Director of Dining Car Cuisine” for the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroads, whose routes became popular because of the food served. Rector was famous enough to have appeared as himself two years earlier in the Mae West vehicle, Every Day’s a Holiday. The author was not the retiring sort.

Rector apparently also had a business to publish many of his own cookbooks: the copyright statement lists the Rector Publishing Company, New York. It is stated at the onset that “It is the intention of this book to give its readers a perhaps finer appreciation of eating, as an art. If it makes any real contribution to that end, it will gratify both its author George Rector and its sponsor Gas Exhibits, Incorporated.” Gas Exhibits was apparently an organization of several hundred utility corporations and manufacturers of household gas products that displayed at this Fair. The mention of the sponsoring company is significant in that it is the only printed (and quite slight) indication that this cookbook was produced for and distributed at the World’s Fair in New York. There is also the inscription “George Rector, World’s Fair,” which helped in its cataloging specifically for the Dibner Library’s World Fairs Collection.

Food was long an essential and popular component of the World’s Fairs, both in exhibitions and for fair goers to sample. The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri has been credited with introducing an incredible (some truthfully, others not or still debated) range of American standards: the hot dog, peanut butter, the club sandwich, cotton candy, and the ice cream cone. The 1964 World’s Fair in New York, where hummus, kimchi, and tandoori were served up, gets attention for introducing more non-Western food to the American public. But the 1939 Fair in Queens had food as its central theme and was influential in promoting fine dining in the United States, which was still struggling to get out of the Depression. The restaurant in the French Pavilion (Le Restaurant du Pavillon de France) was such a success that it led its maître d’hôtel, Henri Soulé, with chef Pierre Franey, to open the chic and long-running Le Pavillon in Manhattan.

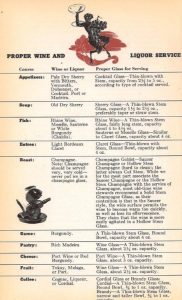

Home at the Range includes a chart, complete with a charming Bacchus vignette, for “Proper Wine and Liquor Service” (Prohibition had remained in place until 1933, just six years before the book was published). There is an emphasis on French sauces, including such standards as Hollandaise, Béchamel, Velouté, and a Bearnaise calling for fresh tarragon. However, there is also a range of nationalities in the culinary repertoire, not just French, perhaps playing to the themes of the World’s Fair or simply reflecting the melting pot of New York City: Meat Balls, Creole Sauce; Borscht, “A Goode Olde New England Clam Bake,” East Indian Curry, Roast Beef with Yorkshire Pudding.” Although the recipe for Spaghetti a la Genovese does not call for basil (just parsley), it is intriguing for its inclusion. The hors d’oeuvres—lots of oysters, cocktail sauce for shellfish, cheese puffs, and olives, California style—appealed for their sophistication. While there is a definite tilt to European cuisine in Home at the Range, there is also a distinct celebration of American food and traditions.

Home at the Range includes a chart, complete with a charming Bacchus vignette, for “Proper Wine and Liquor Service” (Prohibition had remained in place until 1933, just six years before the book was published). There is an emphasis on French sauces, including such standards as Hollandaise, Béchamel, Velouté, and a Bearnaise calling for fresh tarragon. However, there is also a range of nationalities in the culinary repertoire, not just French, perhaps playing to the themes of the World’s Fair or simply reflecting the melting pot of New York City: Meat Balls, Creole Sauce; Borscht, “A Goode Olde New England Clam Bake,” East Indian Curry, Roast Beef with Yorkshire Pudding.” Although the recipe for Spaghetti a la Genovese does not call for basil (just parsley), it is intriguing for its inclusion. The hors d’oeuvres—lots of oysters, cocktail sauce for shellfish, cheese puffs, and olives, California style—appealed for their sophistication. While there is a definite tilt to European cuisine in Home at the Range, there is also a distinct celebration of American food and traditions.

Rector’s cookbook is also a link from the farms and kitchens to increased consumer spending on entertainment. Anxious hosts and home cooks, aspiring to appear worldlier and at ease with pleasure and luxury, could rely on Rector’s recommendations for entertaining guests.

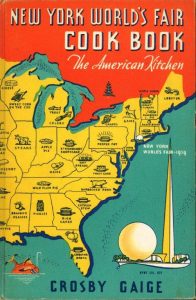

The contemporaneous New York World’s Fair Cook Book: the American Kitchen, (above) by Crosby Gaige (1939), is more typical of the period, with an array of recipes representing every state and region in the country. Yet Rector’s little cookbook reflects more accurately the theme of the entire Fair that year “The World of Tomorrow”— anticipating the food craze of our present day and, oddly, given its sponsor, not much at all about cooking on a gas range.

For further reading:

The American Menu: Rector’s New York City: http://www.theamericanmenu.com/2015/08/rectors.html

Be First to Comment