This post was written by Lauren Eames. Lauren was an intern with the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library, Summer 2014. She is working on her B.A. in Religious Studies at the University of Chicago.

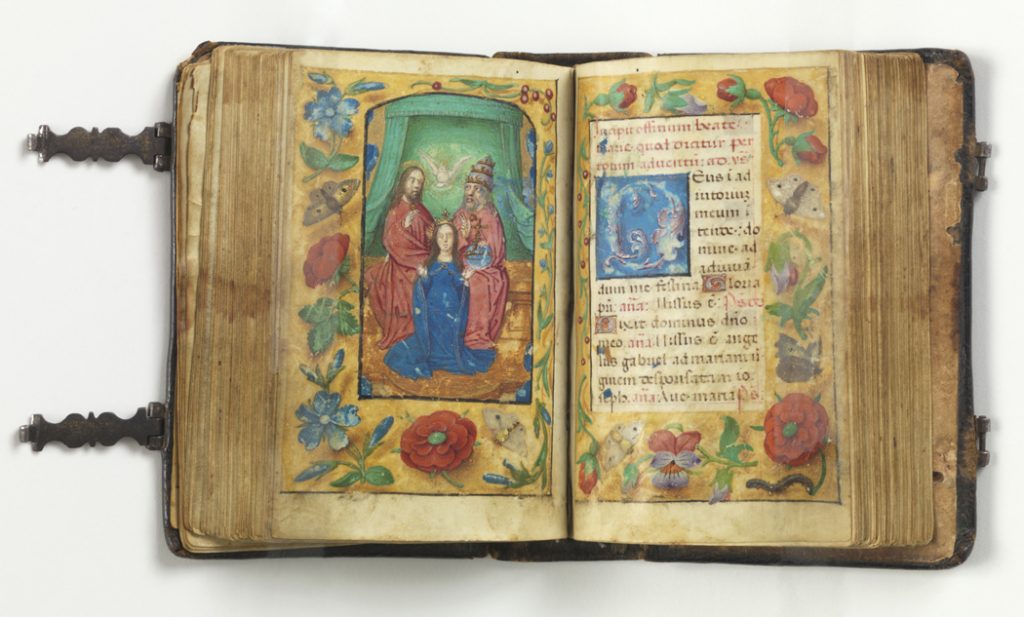

NEW YORK, 1982 – “Recent gifts to the museum library include a 15th-century illuminated prayer book from Northern Europe, featuring five full-page illuminations, historiated and floriated initials, and elaborate border fantasies; it is the gift of Joseph Farber in memory of his wife Caroline.” (Cooper Hewitt Newsletter, Vol. 5 no. 2)

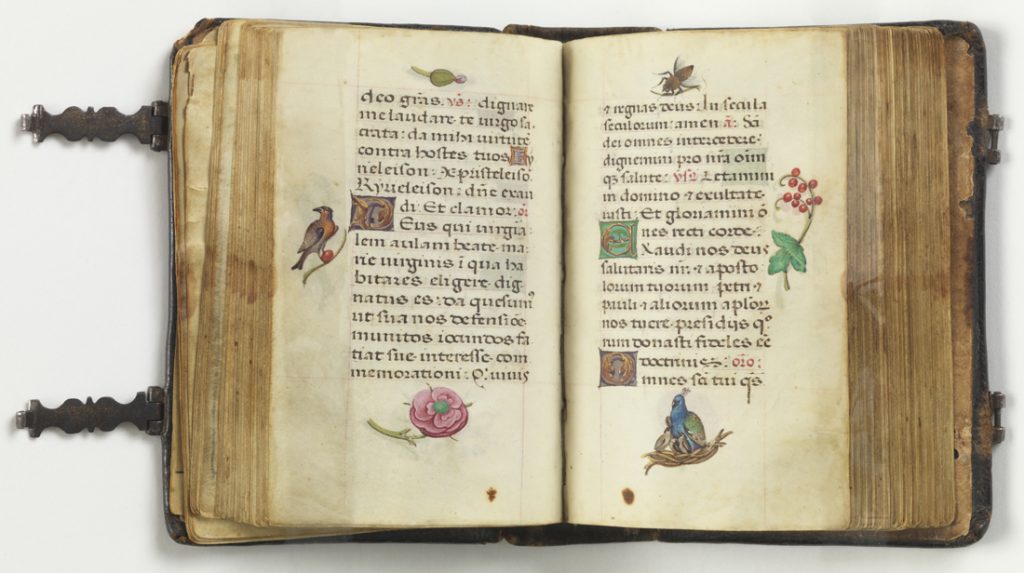

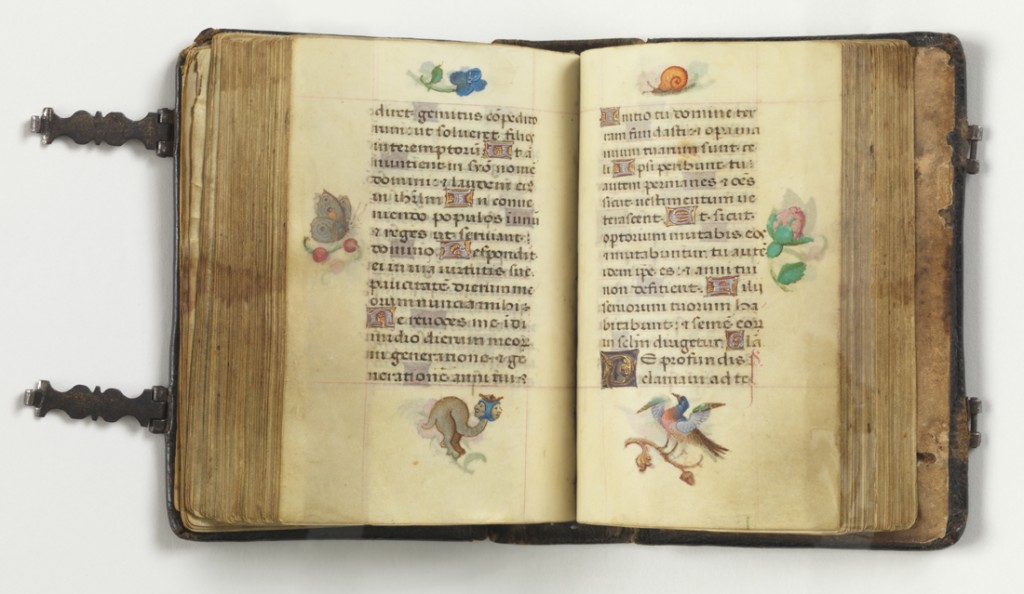

The Flemish Book of Hours is more than simply a prayer book. It typically contains a calendar section, marking the relative importance of Saints’ Days and other Holy Days, as well as the Mass of the Virgin, the Hours of the Virgin, and the Full office of the Dead. During its heyday, the mid-13th century to the mid 16th century, this was the most important and most accessible religious text for the laity. Unlike, for example, the Breviary, Books of Hours were written and illuminated by hand in secular, artisans’ workshops as opposed to in monasteries. Because of this, they were relatively non-standard and included non-religious aspects. Though it was customary to put the calendar first and the Office of the Dead last, the different sections of a book of hours could appear in more or less any order and some parts even varied in content by region. For instance, the responsory parts of the Office of the Dead were particularly prone to variation. Moreover, in addition to being a vehicle for the good word, these books were illustrated with secular scenes of daily life, especially around the calendar sections, and with natural motifs in the margins.

The Book of Hours had important secular aspects. In the 15th century Flemish workshops improved their workflow with standard images and improved writing and illuminating techniques, making the Book of Hours available not only to the nobility but to the then-emerging middle class. It was still a luxury, but a more widely accessible luxury; often, if a household owned any book, they would own a Book of Hours and it served both as a guide to personal devotion and as a guide to literacy as it was often used to teach children to read. It was also quite portable; ours is entirely pocket-sized (9cm x 6cm x 3cm) as many were so that you could pray on the go.

Having begun with the Annunciation, what better way to close than with the coronation of the Virgin (above)? This miniature serves as a perfect introduction to the Advent variations on the Hours of the Virgin. Though they remained the same for most of the year, during the advent season some of the lessons would be different and some of the responses would vary. The image above shows the Virgin decked out in a brilliant blue, which can tell us something about the economic climate of the time during which this book was illuminated; new trade routes opened up high quality sources of ultramarine to Northern Europe (it was mined from a single mine in modern-day Afghanistan), which was used to make brilliant blue paints like we see here.

During the Counter-Reformation (1545-1648), the Vatican issued a papal bull rendering the Hours of the Virgin optional, a coy way of discouraging the practice entirely, and later mandated that anyone who wanted to perform the hours use an official, Vatican-sanctioned Book of Hours. This essentially ended the use of the Book of Hours, but, because they were so immensely popular in their day for both secular and religious reasons, the Book of Hours is the variety of medieval manuscript most likely to survive to the modern day.

2 Comments

I have acquired a Book of Hours. Who and how might I get more information about the version in my possession? Is there someone at the Smithsonian Institute who can direct me to a researcher or appraiser?

Hi Robert,

Congratulations on your acquisition! Unfortunately, the Smithsonian can not offer appraisals. But we do have some resources listed on our website here: http://library.si.edu/information-old-books

Good luck!

Erin Rushing

Outreach Librarian