Now that the time of harvesting grapes for wine in the Northern Hemisphere is coming to a close, let’s raise an appreciative glass and toast John Adlum, known to a few as the “Father of American Viticulture.” The history of wine making in the United States is involved, to say the least (see Pinney’s magisterial work on the subject*) but it was Adlum who nurtured the first commercially viable vine in this country. And he did so, surprisingly but not incidentally, in the nation’s capital.

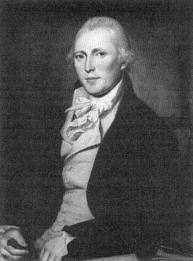

Adlum (1759-1836) was a Revolutionary War veteran, land surveyor and horticulturist, the author of the first monograph on United States viticulture (that is, not British North American and a treatise that focuses on local varieties): A Memoir on the Cultivation of the Vine in America (Washington, 1823). While there is not a copy of this short but important work in the Smithsonian Libraries, it has been digitized by the Biodiversity Heritage Library and there are two copies in the Library of Congress, one with James Madison’s signature.

Adlum’s 200-acre estate, ‘The Vineyard’, was just north from where the Smithsonian’s National Zoo spreads today, in the northwest quadrant of the city. At ‘The Vineyard’, on the banks of Rock Creek, Adlum developed twenty-two varieties of grape, most notably the Catawba, a hybrid of American and European vines (although its precise origins are debated). It soon became “the” grape in the fledgling American wine industry, producing a palatable product for even European tastes.

Previously, no one much liked what was made from indigenous grapes. One satisfied customer was Nicholas Longworth, who took Adlum’s slips back to his farm in Ohio and grew the vine with great success. It also inspired Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to pen “Ode to Catawba Wine”, dedicated to Longworth, the Cincinnati banker. (“But Catawba wine … Has a taste more divine, /More dulcet, delicious and dreamy … There grows no vine … That bears such a grape”).

But it was the Washingtonian Adlum who came to be known as the “Father of American Viticulture.” He wasn’t all that interested in having his own winery. Adlum’s aim was greater. He corresponded directly with Thomas Jefferson, one of American’s first and greatest oenophiles, on his wine-making efforts and shared the product of his work. Jefferson, who famously failed over decades to grow imported vines at Monticello, urged Adlum to cultivate a domestic grape. In the new country, it was time to have a wine-making industry to lessen the dependence on foreign imports. A very popular treatise on all practical aspects of horticulture, The American Gardener, also printed in Washington City (as it was known then) declared: “Before this little volume is sent into the world, the Editor thinks it a duty to say a few words upon the very important subject of Vineyard planting, than which there cannot be imagined a national object of great magnitude, or of consequences more desirable.” The book, without attribution, quotes from a letter of Jefferson’s to Adlum:

I think it would be well to push the culture of that Grape, without losing our time and efforts in search of foreign Vines, which it will take centuries to adapt to our soil and climate. The quality of the bottle you sent me before, satisfies me that we have at length found one native Grape inured to all the accidents of our climate, which will give us a Wine worth of the best Vineyards of France.

The first edition of The American Gardener, adapting English kitchen gardening methods to the Atlantic coast, was in 1804. Many printings soon followed, the Dibner Library has the fourth edition (SB93 .G37 1831). The authors promoted a national wine industry not only for the pecuniary advantages but also for the social and moral benefits of domestic production, stating that there is less drunkenness in wine-making countries.

Soon enough, many American gardening books felt the need to address the growing popularity of make-your-own-wine. Indeed, Andrew S. Fuller in The Grape Culturist (New York: Orange Judd, 1865; SB389 .F96 1865 SCNHRB) was irritated enough at this expectation to respond to questions on why a treatise on wine making was not included in his book: “It is not every one who attempts to make wine that accomplishes it for every vineyardist does not know how to make wine any more than every wine maker knows how to grow grapes.”

Adlum more boldly promoted the idea of a Government Experiment Station in the second edition (1828) of A Memoir, stating that he had attempted to interest the President of the United States to buy public land in order to “procure cuttings of the different species of the native vine to be found in the United States, to ascertain their growth, soil, and produce, and to exhibit to the Nation a new source of wealth which had been too long neglected.” The existence of such places came much later, particularly with the enactment of the Hatch Act (1887) and the establishment of the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. (1927). Congress finally appropriated federal funds with the Hatch Act—what Adlum tried hard to get legislated—to nurture commercially supportive agriculture and technical research at state land-grant colleges. And by 1915, the Department of Agriculture produced the professional paper, Testing Grape Varieties in the Vinifera Regions of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office; SB389 .H87 1915Z Botany).

Adlum was before his time. Cheers to him!

Julia Blakely

Special Collections Cataloger

Robin Everly and Diane Shaw helped with this post.

*Pinney, Thomas. A History of Wine in America from the Beginnings to Prohibition. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1989, is one volume in the author’s history of the subject.

4 Comments

Wonderful article. For those of you in the Cincinnati area or visiting, the invaluable Lloyd Library has an exhibition of Grape Related books and manuscripts on display now through the middle of December dating from this era.

Thank you. And Nicholas Longworth’s home is now the Taft Art Museum, correct? I wonder if there are any traces left of his winery.

I don’t believe so, its too old!

[…] https://blog.library.si.edu/2014/10/wine-and-washington/ […]