This post was written by intern Becca Greenstein. Becca is currently pursuing her Master’s in Library Science at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. She has always had a passion for research, teaching/helping others and seeing the direct impact of her work, and collaboration across departments and institutions (and, of course, reading), so library school has been a good fit for her. After she graduates, she hopes to continue honing these skills while working in an academic or special library as a science librarian.

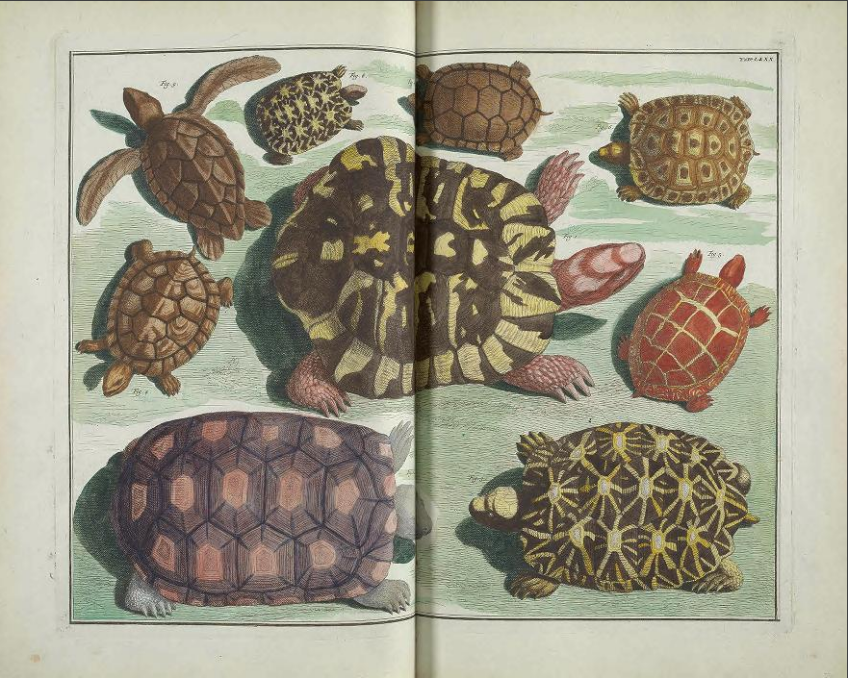

“Every one knows what a bird is,” asserts an early 20th century book that I found while browsing the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). As I’ve learned during my Professional Development Internship with Jacqueline Chapman at Smithsonian Libraries this summer, it’s not always that simple. Taxonomy* is ever-changing, especially at the granular level needed by subject specialists around the world who use BHL to conduct research on organisms ranging from mosses to turtles to fungi. BHL is a consortial digital library, whose member libraries digitize works in natural history and botany, based on both user requests and subject librarians’ selections. My project for this summer was to refine a collection assessment methodology for BHL using both taxonomic and bibliographic analyses. Along the way, I’ve learned valuable lessons in using library tools, troubleshooting in Python (a computer programming language), and understanding the thought processes of 19th century ornithologists and pteridologists (botanists who study ferns).

Last year, Jackie worked with Robin Everly, the Smithsonian’s Botany and Horticulture Librarian, to conduct a taxonomic and bibliographic analysis to assess the depth of the BHL’s fern and lycophyte literature. They presented their results at an international conference on ferns, Next Generation Pteridology , and had the unique ability to talk with many subject-specialist users from around the world. Jackie later shared this proof-of-concept with researchers at TDWG in Nairobi, Kenya.

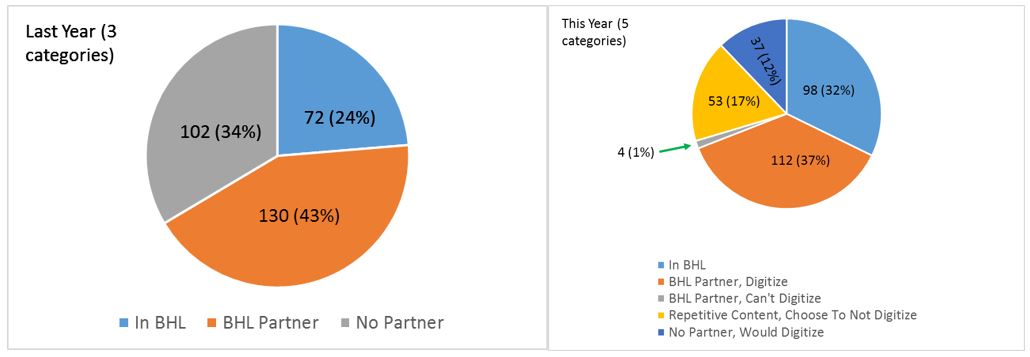

For the bibliographic portion of the project, Fern Books and Related Items in English before 1900 was referenced to determine whether a book was available on BHL, and if not, if we had access to it. A year later, I furthered this analysis by seeing what has changed in the past year and making requests for partner libraries to scan items to add to the collection. I enjoyed gathering data for books with titles such as Greenhouse Ferns and the Romance of Plant Life, Rambles in Search of Ferns, and The Fern Paradise: A Plea for the Culture of Ferns. As the bibliography used included all editions of a particular work, regardless of whether the content had changed, I decided to not digitize the 53 works whose content was already in BHL in another edition of the same work. As you can see by the charts below, the number of fern books on BHL from this list has increased by 36% over the past year. The 112 resources that we have access to via partner libraries will be in BHL after they are digitized. We lack access to only 37 out of 304 books that would add content to BHL, and it will be interesting to follow up with this study to see if current partners acquire new resources or if new partners that possess these materials join the BHL Consortium.

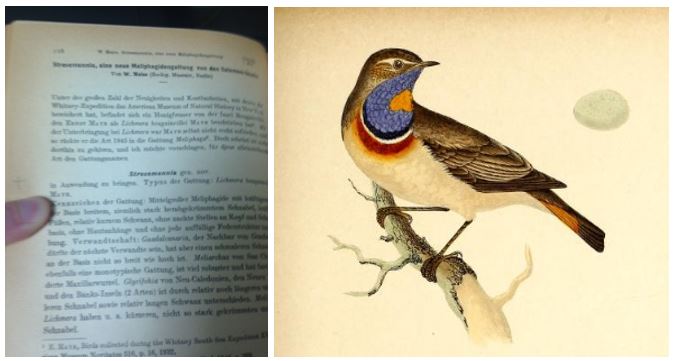

For the taxonomic portion of the project, BHL’s coverage of a particular taxonomic grouping using scientific names was analyzed. The digitized material on BHL is in the form of images, which the computer does not recognize as text. Using Optical Character Recognition (OCR), the images are converted to machine-readable text. Taxonomic Name Recognition (TNR) then searches the OCR to find scientific names using multiple recognized lists of scientific names. To use this powerful analytical tool to analyze BHL’s literature on birds, I upgraded last year’s Python 2 code to Python 3, the newest version of the programming language. Using my code, I counted the number of mentions of each genus of birds, as determined by TNR, to identify potential gaps in the BHL collection**. Of the 2234 genera analyzed, 99.6% of them are mentioned in the BHL corpus, 131 individual genera had more than 10,000 mentions in BHL, and 88% of them had more than 100 mentions. I conducted an in-depth analysis of all 37 genera with fewer than ten mentions in BHL to figure out possible reasons for the paucity of literature. Some of the genera were described within the past 20 years, some birds are endemic to far-away (to 19th century European ornithologists) places like New Guinea and Mozambique, and some genera have undergone changes in their taxonomy over the years. I then looked for the first mention of each genus in books and journal articles online and in print, in addition to submitting scan requests for the books we have access to that weren’t already in BHL. There was something surreal about trekking up to the Birds Library, which is tucked away on the sixth floor of the National Museum of Natural History, finding Ornithologische Berichte on the shelf (and no, I don’t speak German), and opening to page 118 to find Wilhelm Meise’s initial description of Stresemannia bougainvillea.

I was at the Smithsonian Libraries for six weeks, but it did not feel like that long. I hope that BHL will use my code to analyze larger sets of data and/or data at a higher level (how is BHL doing at collecting literature on Kingdom Animalia?). Through conducting my project, I’ve learned that things you learn in library school really do apply to the real world, how an academic library at an institution without students functions, and the workflow behind digitizing materials that appear in BHL and on the Smithsonian Digital Library. I’ve learned that library tools we take for granted can be unreliable, but aren’t usually, and that getting help from people who do research on ferns and those who do speak German can be very beneficial. I hope to bring the things I’ve learned back to my final two semesters of library school, as well as into my hoped-for career as a science librarian after I graduate.

*For a good introduction on taxonomy (the classification of organisms), see this Convention on Biological Diversity page.

**Kingdom is the largest taxonomic group, followed by Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species. Each Kingdom has multiple Phyla, each Phyla has multiple Classes, etc. My search on the genus level was thus very granular, in order to be more useful to subject specialists.

One Comment

Very impressive work! Sounds like your 6 weeks were well spent.