Interested in culinary history and books? Join us on Wednesday, November 16th for our Annual Adopt-a-Book Evening, featuring a food and drink theme!

Slavery and freedom, the Revolutionary War, New England’s maritime culture and life, Colonial revivalism, trade, women’s role in the economy, the development of regional cuisines, the not-fully-explored history of African Americans in the North. More than just molasses, spices and rum, there is a heady mix of history in the Joe Frogger. Can all these ingredients of America’s past be found in a cookie?

This heritage is being celebrated by the innovative cafeteria of the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, where this sweet is featured. Appealing to different senses, the Joe Frogger cookie evokes a different time in a way that only a food (particularly a baked one) can do. The Sweet Home Café, in four stations – Creole Coast, Agriculture South, Western Range, North States – is really a continuation of the museum’s exhibitions in their curated selection of dishes.

Despite being a native coastal New Englander and baker, I wasn’t aware of the Joe Frogger cookie when the museum’s recipe appeared in the food section of The Washington Post. Baking up a batch, however, produced such a familiar smell and taste and a vague memory of a visit to Sturbridge, Massachusetts. That sent me to my own cookbook collection to find other versions of the Joe Frogger. There were surprisingly none, although similar recipes appear frequently in old volumes of Maine and Massachusetts imprints, minus the intriguing and essential addition of rum.

Despite being a native coastal New Englander and baker, I wasn’t aware of the Joe Frogger cookie when the museum’s recipe appeared in the food section of The Washington Post. Baking up a batch, however, produced such a familiar smell and taste and a vague memory of a visit to Sturbridge, Massachusetts. That sent me to my own cookbook collection to find other versions of the Joe Frogger. There were surprisingly none, although similar recipes appear frequently in old volumes of Maine and Massachusetts imprints, minus the intriguing and essential addition of rum.

Reflecting the resurgence of interest in ancient recipes and local cooking, there are many recent versions of Joe Froggers on the World Wide Web, including ones from the kitchens of well-known food figures as Maida Heatter, Martha Stewart and Nigella Lawson. There are also as many variants on the history of the unusually named sweet. The Post article stated that they “date back to Joe Brown, a volunteer in the Revolutionary War. Legend has it that at the tavern Brown owned, ‘his wife would make these molasses cookies. When they baked up, they were as large as the lilies on the frog pond outside the tavern.’”

Origins of recipes are notoriously difficult to pin down and stories get muddled in the retelling. And with the Joe Frogger there is a trivialization, or reducing the figures to caricatures, creeping into the narrative. Some tales credit the invention of the cookie to Joseph Brown himself. He had received a bottle of rum from a neighbor and then would exchange cookies for rum. Others mistakenly transform his wife, Lucretia, to being his daughter. Also known as Aunt ‘Crese, she was said to have named them after the shape the batter took as they were thrown in a skillet, looking like frog legs. Another unlikely account says they were named for the plump and dark frogs they resembled. The cookies are actually large and flat, more suggesting a lily pad.

The more complete history is far richer and deeper, much like this tasty molasses cookie. The Smithsonian Libraries’ culinary collections and books on food and economic studies, scattered in different repositories, provide much (but not all) of the story. The extremely helpful publication, African American Historic Burial Grounds and Gravesites of New England, begins to establish the record with its detailed genealogical research.

Joseph Brown (1750-1834) was the son of an African-American mother; his father a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard. Born into slavery, Brown may have been freed for his Revolutionary War service. He had enlisted in January 1776 in Captain Francis Felton’s Company of militiamen in Marblehead, Massachusetts. His widow received his military pension. The citizens of the town erected a new memorial for Brown in Old Burial Hill in celebration of the American Bicentennial. It reads: “Marblehead’s ‘Black Joe’ a Revolutionary Soldier & Respected Citizen.”

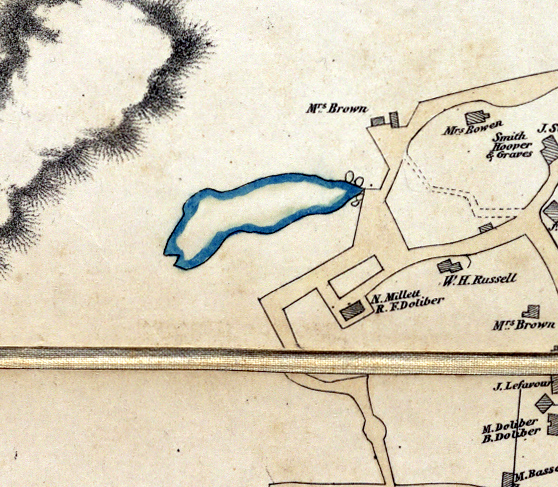

Lucretia Thomas Brown (1772-1857) was born in Marblehead, the daughter of two former slaves of Captain Samuel Tucker. Joseph and Lucretia Brown were able to remain in Marblehead when unemployed freed blacks were forced from town in the late 1780s. In 1795 the couple purchased one-half of a home, along with Joseph and Mary Seawood. The Browns were eventually able to own the entire saltbox (a New England colonial style of architecture with two stories in front and one in the back, all roofed with a steep pitch), which had been built in 1691. There, on Gingerbread Hill next to a mill pond, they both resided and ran a tavern. Lucretia maintained the home following Joseph’s death for twenty-three years, selling homemade perfume distilled from rose petals and baking wedding cakes to augment her income.

Unlike its present incarnation as a wealthy enclave and yachting center within commuting distance of Boston, Marblehead was once a rough and tumble seaport. The old part of town was the commercial center with wharves and warehouses. Fishermen, sailors and other workers marginalized in the Puritan society would gather at the integrated “Black Joe’s” tavern for drinking, dancing and gambling. Marblehead was known for its particularly tough breed of sailor. Life on the sea and stretches of unemployment on land, along with dependency on the merchant class, made for the formation of social drinking communities, and the maritime towns were full of such pubs. Marblehead was distinguished at the time by the number of its liquor-related crimes. Isolated and poorer than God-fearing Salem, the town had never regained its prosperity following the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 which irreparably damaged the fishing fleet. This accounts, in part, for the large number of Colonial-era buildings that survive, including the Brown’s home and tavern.

There would be some food provided to the patrons at “Black Joe’s” tavern, where women and children also gathered. According to Marblehead lore, Lucretia developed her cookie there. As an African-American woman, cooking would have been one of the few means available to her to make money. The “original” recipe of local tradition contains (maybe) seawater and no eggs. This, along with the preservative qualities of the rum, ensured that the cookies would have kept on voyages long after leaving the harbor, such as those in search of cod off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. This quality led to the fame of the Joe Frogger. There is a children’s book, Molly Waldo!: a young man’s first voyage to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, adapted from the stories of Marblehead fisherman of the 1800s, that works this into its story, along with the recipe, in the Smithsonian Libraries’ collections.

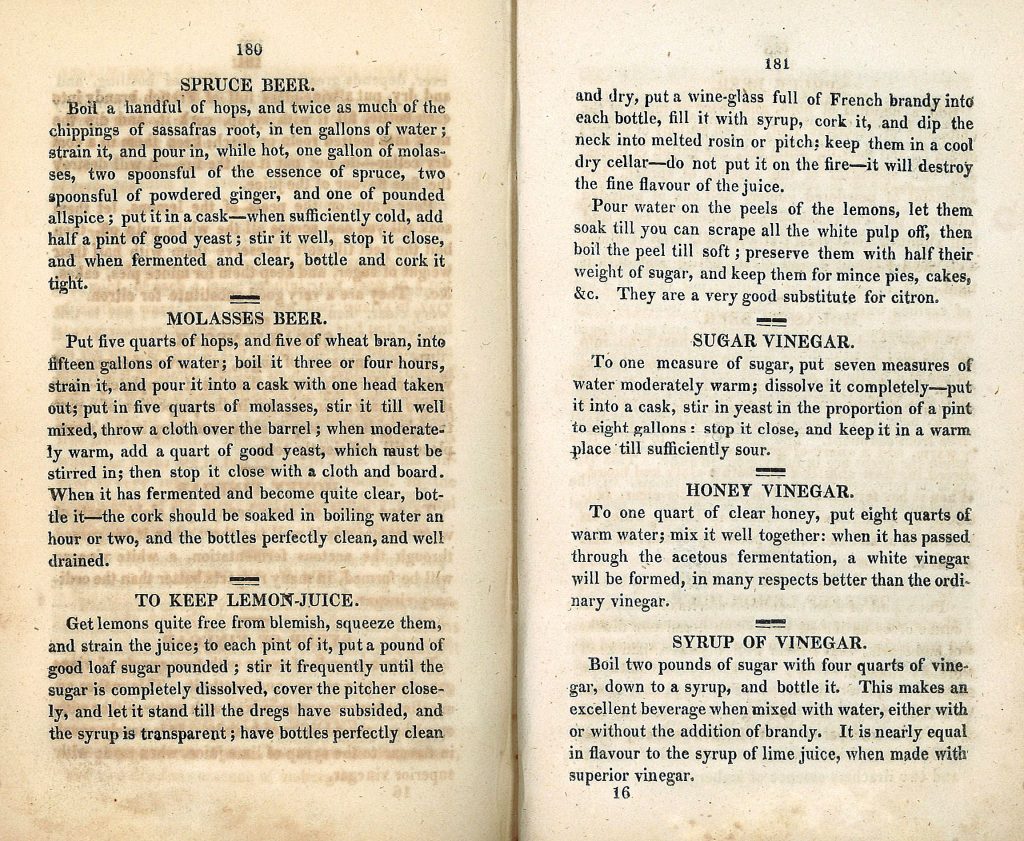

For beverages, “Switchels” (a mix of molasses, water, vinegar, and sometimes rum and ginger – it was the energy drink of the day), homemade molasses beer and domestic rum would have been served. “Black-strap” originally was not a type of molasses but a tavern drink made with rum and additional molasses. Rum was by far the most important drink in 18th-century America, with consumption estimated to be twenty-four pints per annum, per person.

Molasses, a by-product of refining sugar, is the basis of rum, which was widely distilled in the American Colonies. By 1770, there were ninety-eight rum distilleries in New England alone, producing a far less expensive commodity than that imported from the West Indies. But all were bound up with slavery and the slave trade. Slaves performed the hazardous work of producing sugar. Some New England rum was exported, part of the essential flow in the infamous “triangular” circuit, as pointed out in America’s Founding Food. Some of the rum was sent to West Africa where more enslaved peoples were purchased for the West Indian sugar work force. And “refuse” cod (of the lowest grade), that didn’t have a market in Europe, was sent from New England to feed slaves.

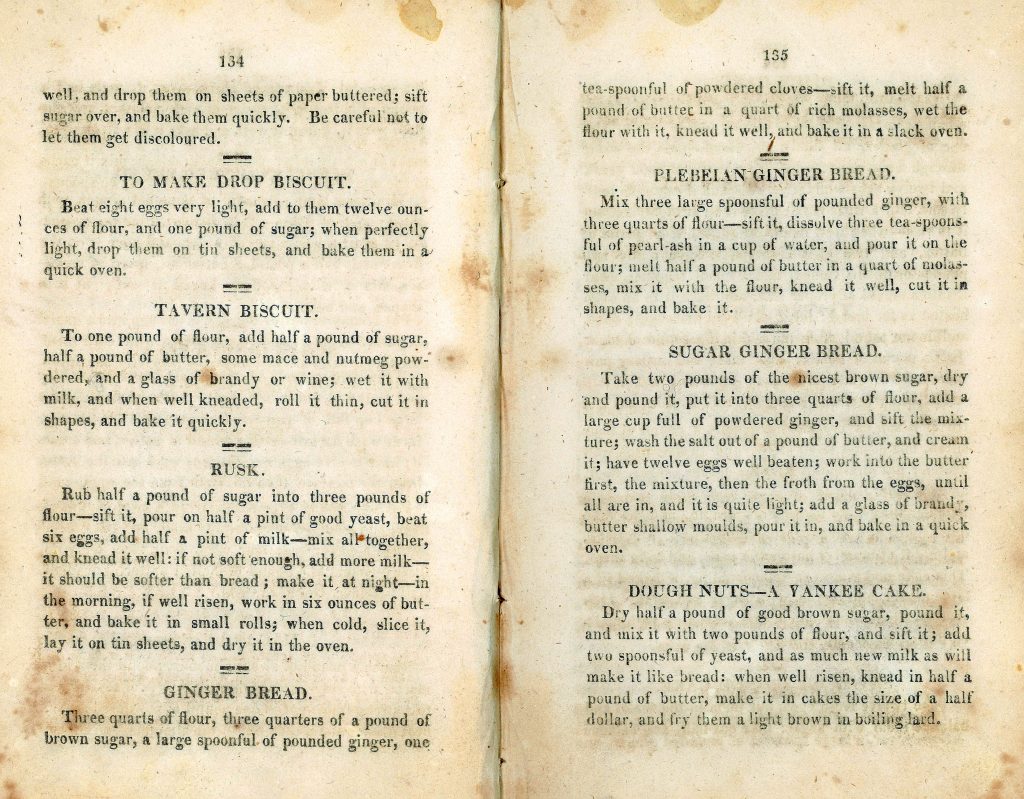

Joe Froggers, essentially gingerbread in cookie form, may have originally been sweetened with just the molasses, even though more expensive refined sugar was readily available. Lard would have been used rather than butter (1950s versions still called for shortening). Old Sturbridge Village, an outdoor living museum recreating a New England town of the 1830s, founded in 1946, appears to have revived the cookies. Recipes started to be published in newspapers and magazines of the 1950s. The Old Sturbridge Village bakeshop still sells Joe Froggers.

Was there ever indeed an authentic recipe containing these ingredients created by Lucretia Brown and named for her husband? Or is this a fable fed by a close and often closed-off community’s shared past? Marblehead, occupying a rocky peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic, was isolated from main roads. Another intertwining element of the story is that the “Joe Flogger” (spelt with a ‘l’) was also a ship’s provision on voyages along the Atlantic seaboard. A “Joe-flogger” is variously identified as a pancake stuffed with raisins or prunes, a fried cake, or turnover, or simply New England slang for any type of pancake.

In Dorymates: a Tale of the Fishing Banks (New York, 1889, page 81): “Thus it was late in the evening before the exhausted lad tumbled into his bunk, where he dreamed of monstrous fish with twenty-dollar gold-pieces in their mouths that turned into Joe-floggers as he reached for them.” Was the “frogger” name a play on this baked good, recalling Joe Brown’s pond, or a later addition to the standard sweet? Or was this merely a more colloquial spelling of the word? Fishermen and sailors have always had a language all their own. Nautical food dialect is full of idioms such as duff, cautch, grummet, grunt.

There is a recipe for “Tavern Biscuit” in The Virginia House-Wife or Methodical Cook, by Mary Randolph, calling for either wine or brandy. There was a tradition of serving spiked cookies and gingerbread. The Dibner Library holds a copy of the fourth edition (Washington, 1830) of this cookery book, written by a relative of Thomas Jefferson’s.

The cookie could have well been the signature creation of the resourceful Lucretia Brown, the recipe surviving by oral tradition in proud, independent Marblehead before making its way to the printed page much later. The first full-fledged cookbook by an African-American was not published until 1866 (a reprint of this rare work is in the Smithsonian Libraries). Landmarks in Marblehead testify to the lore, to the Brown family’s role in the community and not to stereotypes. There is Joseph Brown’s commemorative grave, the pond named for him, as well as the nearby wooded Conservation Area, established in 1973. Along with the home’s (still private) identifying sign of Joe Brown’s tavern, the couple were never excluded, even if not fully documented in, from Marblehead’s history.

The Joe Frogger can be seen then as a unique African-American food and a distinctively New England creation. Spice cookies (called variously small or tea cakes, biscuits, jumbles in early cookbooks) along with gingerbread, were developed in 17th-century England and recreated in the Colonies, flavored with molasses (“treacle” in some old recipes). Joe Froggers are so entwined with one specific place and time that the history is unlikely to be all myth. The cookies, like the other hardy New England-fare of Boston baked beans, Boston brown bread and Indian pudding, all flavored with molasses rather than expensive sugar, have come to exemplify a strong element of the frugal, stoic character of the Yankees.

These simple cookies may well have been one way for Lucretia Brown to achieve economic independence after Joseph’s death. Twenty-two years her husband’s junior, she stayed on in the Gingerbread Hill home for the remainder of her life, passing the saltbox to their daughter Lucy Ann R. Brown Fontayne (or Fountaine, 1831-1893), who lived there until selling it in 1867. Lucretia was buried in the newer, spiffier Waterside Cemetery rather than the Old Burial Hill where she reportedly visited Joseph’s grave daily and collected rose petals.

The stated mission of the Museum of African American History and Culture is to be a lens through which to understand what it is to be an American. The Joe Frogger cookie is but one of the means, a distinct and delicious contribution to the social history of food. And the Smithsonian Libraries’ various collections help to interpret the story. Cookies and books, preserving a heritage. The Libraries’ newest branch will soon open within the museum, staffed with a librarian, archivist and a genealogy specialist to guide researchers in such quests.

Notes and Further Bibliography

Many of the cookery books and culinary histories in the Smithsonian Libraries were donated by the Culinary Historians of Washington, D.C.

The earliest recipe I found in the ProQuest database of Historical Newspapers was May 2,1954 in the Los Angles Times. Old Sturbridge is mentioned in the article.

Bradlee, Francis Boardman Crowninshield. Marblehead’s foreign commerce, 1789-1850. Essex Institute, 1929.

Colcord, Joanna Carver. Sea Language Comes Ashore. New York, [1945].

Goode, G. Brown. The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. Washington, 1887.

Nodjimbadem, Katie. What 200 Years of African-American Cookbooks Reveal About How We Stereotype Food. Smithsonian.com

Randolph, Mary. The Virginia House-wife, or, Methodical Cook. Washington, 1830.

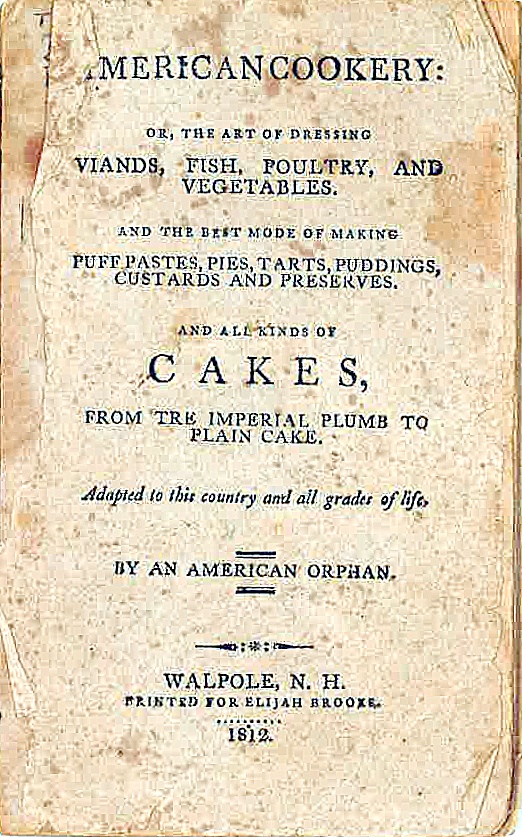

Simmons, Amelia. American Cookery. Walpole, New Hampshire, 1812.

Stavely, Keith and Kathleen Fitzgerald. America’s Founding Food. Chapel Hill & London, 2004.

Stavely, Keith and Kathleen Fitzgerald. Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Book in New England. Amherst and Boston, 2011.

Tannahill, Reay. Food in History. New York, 1989.

Tipton-Martin, Toni. The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. Austin, 2015.

Williams, Ian. Rum: a Social and Sociable History of the Real Spirit of 1776. New York, 2005.

Recipes with history:

The Boston Globe, Recipe for Joe Froggers

The History of Joe Frogger Cookies

Joe Frogger Cookies from Marblehead

Marblehead Magazine: Marblehead Recipes

New England Recipes

New England Today

Save

13 Comments

Scrumptious, without the rum. Gre up eating them.

Joseph and Lucrecia Brown are buried in the Waterside Cemetery in Marblehead, next to Lucy Fontaine. There are also many records such as vital records that document Joseph and Lucrecia’s marriage in 1793. Apparently Joseph was a Revolutionary War vet and after Joseph’s death, Lucretia continued to collect a pension until her death in 1857. Julia, send me your email address and I will send you some pictures of the actual (not commemorative) grave site. I did though, take a picture of Joseph’s commemorative grave too.

I passed ‘Joe’s’ regularly on the way to Gracies for swimming. Also did a lot of fishing & skating there. Currently, a classmate resides in the ‘Tavern’.

Family history indicates that a distant relative of mine (William Peach) was born at what is now known as Black Joe’s tavern. William was born in 1776. William’s father was also named William Peach and it is reported that he and his wife owned the property known today as Black Joe’s tavern where the younger William was born. I have no idea how long a Peach owned the property. Peach roots seem to grow out of England, then branches migrated to the East Coast and later eastward to the midwest and here to Illinois where I am from and reside. Is there line of ownership that’s been published or is somehow available?

Roger, see this link that refers to the dead of the property and Peach ownership: https://www.legendinc.com/Pages/MarbleheadNet/MM/Articles/BlackJoe.html

A source isn’t cited so you may start with the Marblehead government: https://www.marblehead.org/public-records-requests

Also, a look at the Registry of Deeds in the MA State Archives and the collections in the Philips Library of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem might be fruitful.

Julia

thank you for publishing this article on the web…i am originally from the west coast of canada…my grandmother used to cook these yummy cookies (and she called them by the original name)…i lost the recipe in a move and couldn’t find the recipe anywhere….there are variations using shortening, even butter but Granny used lard. …i know it isn’t considered “healthy” but it really makes the froggers taste great and really, how many cookies can one eat when they are snatched up as fast as i could remove them from the oven? (most of my friends made me promise to let them know when i was baking them)…and my grown children are thrilled to have the “original recipe”…but they still like it when i bake the cookies.. …they say the joe froggers bring back many happy memories…happy cookie eating everyone… 🙂

What is the original recipe? I would love to have your recipe to make these for my son who loves ginger and molasses. The recipe I have for Joe Frogger’s turns out too hard.

Marianne

I’ve done some follow up research regarding my prior post in 2018. Here are the basics for the four people represented together in the Waterside Cemetery in Marblehead, Massachusetts. These are: Joseph Brown, Lucretia Brown, Lucy Ann Read Brown Fountain, and James Fountain.

Joseph Brown

Born November 18, 1749 in North Kingstown, Rhode Island.

Enslaved to Sheriff, Beriah Brown of North Kingstown, Rhode Island.

Obtained his freedom as a substitute for Beriah’s son, Christopher Brown in the Rhode Island Militia.

Served in the 1778 Battle of Rhode Island.

May have served from February 1777 with the Second Rhode Island Regiment and the Rhode Island Regiment through the Revolutionary War and the disbandment of the Rhode Island Regiment in 1783.

Moved to Marblehead after the war.

Married Lucretia Thomas January 5, 1794

Applied for and received a pension in 1832.

Died April 1834

Lucretia Brown

Her father was from Jamaica, Peter Thomas.

Her mother was Levinia Trevitt from Lynn, Massachusetts.

Had at least two other sisters that were bakers in Salem.

Lucretia was born 1774.

Lucretia’s adopted daughter, Lucy Ann Reed Cooper, was also the granddaughter of an (as yet) undetermined sister of Lucretia. Making Lucretia Lucy’s great aunt Creasie[?].

As his widow, Lucretia collected Joseph Brown’s pension until her death in 1857.

Lucy Ann Read Brown

Assisted Lucretia in her older age including the collection of her widow’s pension.

Was named sole inheritor of Lucretia’s estate in Lucretia’s will.

Married hair dresser/widower James Fountain on November 20, 1844.

James W, Fountain

Was recruited into the 54th Massachusetts Regiment in Salem, MA in 1864. He served in the overflow 55th Massachusetts Regiment.

Operated a barber shop in Salem, Massachusetts until his death.

Hi Curtis,

I’d be very interested to learn more about the history and life of Joseph Brown. Could you share your sources. I’d be most appreciative!

We love Joe Froggers and my daughter is an intern at Old Sturbridge Village! So I was VERY suprised to read about the connection to Sheriff Beriah Brown, who is a very distant Uncle. (His father was also Beriah Brown, from whom we descend). Thanks for that interesting bit of history!

[…] They are a New England favorite dating back to the 18th Century. Its history is so storied about an African-American New England Revolutionary solider; this cookie is even highlighted in the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture. […]

[…] if you want to go down a rabbit hole learning about Joseph and Lucretia Brown and their cookies, Unbound is a good place to […]

[…] “Joe Froggers: The Weight of the Past In a Cookie.” Julia Blakely. Unbound, Smithsonian Libraries. November 1, 2016. https://blog.library.si.edu/blog/2016/11/01/joe-froggers-weight-past-cookie/#.X05T3i2z3VB […]