Along with time, humankind invariably changes the landscape. The geography and a series of events and errors that occurred in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on December 6th, 1917, contributed to the most catastrophic and dramatic man-made violence to a surrounding area and its inhabitants before the Atomic Age. In the annals of disasters of the 20th century, including the Great War, the explosion that occurred at the Canadian harbor was particularly horrifying and cruel. It was if the battles of the Western Front had crossed the Atlantic in a flash and ruined the bustling, prosperous seaport.

The resources of the Smithsonian Libraries help to recreate the landscape of the past. They provide a better understanding of the setting and why the disaster happened where it did. The records also serve as a memorial and commemoration of what once was on this significant anniversary.

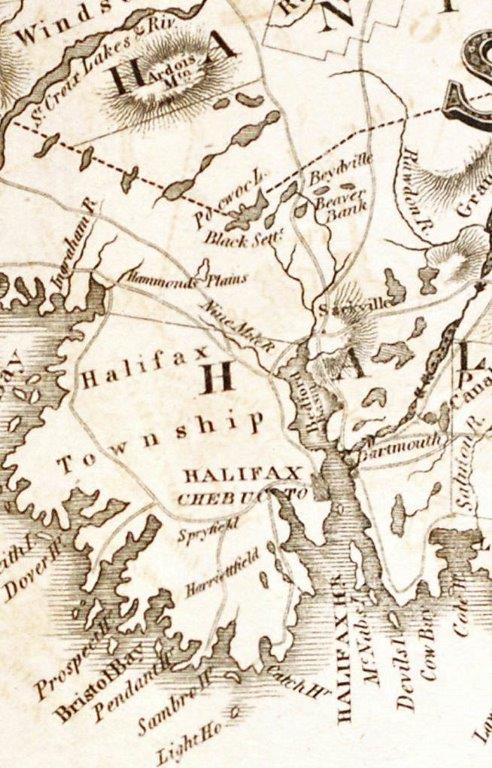

Halifax Harbour is an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean on the south shore of the Maritime Province, one of the deepest ports in North America. A rocky peninsula of the city juts out into the harbor, with the community of Dartmouth on the eastern side. There was also the Mi’kmaq village of Turtle Grove on this shore. The indigenous peoples called the waters of Halifax K’jipuktuk (pronounced “che-book-took”) or “Great Harbor” and had occupied the area long before the French established the colony of Acadia there in the early 17th century.

Scottish geologist Charles Lyell wrote a popular travel and scientific book, Travels in North America, in 1845. Sir Lyell was taken with the speed and ease of access to the continent that Halifax provided. He noted that “Nova Scotia is usually known to strangers by its least favourable side, — its foggy southern coast, which has, nevertheless, the merit of affording some of the best harbours in the world.” (page 163, vol. 2). And, “On the eleventh day of our voyage [from Liverpool, England] we sailed directly into the harbor of Halifax, which by its low hills of granite and slate, covered with birch and spruce fir, reminded me more of a Norwegian fiord, such as that of Christiania, than any other place I had seen.” (page 3, vol. 1).

The protected, ice-free harbor long had been an attractive anchorage. This, and its relative proximity to Europe, provided a convenient waypoint in the crossroads of the Atlantic Ocean where ships could put in for repairs and to resupply, often traveling to and from New York City. Industry and a dense concentration of population developed throughout the 19th century.

A tourism brochure sets the scene of Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, at the beginning of the 20th century:

From the summit of Fort George, better known as Citadel Hill, a superb view of the city, the harbor and the surrounding country may be obtained. The older portion of the town lies between it and the water, and the straight cross-streets lead the eye down to the harbor, where vessels bearing the flags of all nations are at anchor. On a clear, sunny morning the scene is one of the prettiest sights imaginable. To the north, shimmering in the summer sun and specked with the wings of pleasure boats, lie the bright waters of Bedford Basin, into which the harbor opens out after passing through the Narrows. To the east are the low hills on the Dartmouth side, and George’s Island, green and well-kept … Below and around are the buildings of the town, with here and there a spire rising from among green foliage.

– Beautiful Nova Scotia: The Ideal Summer Land (Yarmouth Steamship Company, 1901)

It was in the Narrows, connecting upper Halifax Harbour with the inner Bedford Basin, that two ships which were part of the war effort collided. The French cargo ship, SS Mont-Blanc, having left New York loaded with explosives destined for the battlefields of Europe, was en route to Bordeaux, France. She traveled very slowly, about one knot, towards the secluded Bedford Basin after spending the night at the mouth of the harbor. The New York-bound Norwegian SS Imo, working for the Commission for Relief in Belgium, had been moored in Bedford Basin, delayed while awaiting a late delivery of coal and the crowd of ships organizing for a military convoy. Both vessels could not move into or out of the harbor until the two sets of anti-submarine underwater nets, protection from the increasing threat of German U-boat attacks, had been lifted at the entrance to the port in the morning.

The harbor’s strategic location always made for a prominent role in the city of Halifax’s military engagements. Edward Cornwallis fortified the settlement in 1749 as a counter to the French presence in Louisbourg, Cape Breton. Forces at the Halifax British Royal Navy Yard were used to blockade American ports during the War of 1812. The frigate USS Chesapeake was brought here as a prize. But Halifax had never been besieged.

From the start of the First World War, along with the port of Sydney in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Halifax was the point of departure for most Canadian and some American soldiers deploying overseas. Convoys carrying troops, animals, munitions and other supplies assembled at Halifax Harbour, making it the country’s most important naval base for both World Wars. The city was also the return port, including for hospital ships. The British Admiralty had retaken command from the Canadian Navy during at the start of the war and rescinded the civilian prohibition of ships with dangerous cargo to be in the harbor.

Harbors have a set of rules and regulations for ships navigating its confines, which require local pilots to be on board for help steering through unfamiliar waters. The two vessels, both with Halifax guides, should have passed port to port (the left side of each ship). The out-bound Imo, reportedly traveling faster than what was considered safe, entered the Narrows squeezed to the far left to allow an incoming ship to pass and stayed on that course to avoid a tugboat, but, in so doing, headed into the path of the in-bound Mont Blanc. Warning signals were ignored until it was too late. Both captains, realizing the imminent danger, steered in the same direction and, in the tight quarters, collided.

The impact of the two vessels occurred at about 8:45 am. The Mont Blanc ignited, and the fire quickly went out of control as she drifted toward a pier. In addition to its full cargo of TNT, the ship’s hull and deck were crammed with barrels of highly flammable benzole (a fuel) and picric acid (an explosive) as well as guncotton (a propellant or low-order explosive). This made the Mont-Blanc a massive bomb, and 20 minutes after the collision it went off. The resulting blast, at 9:04:35 am., was the largest man-made explosion before nuclear weapons.

Sailors on other ships, dock and factory workers, military personnel and residents, including children on the way to school, had gathered initially to watch the amazing sight of the blazing ship, unsuspecting of the imminent catastrophe. The sudden, massive and deafening fireball flattened a 1.5 square-mile area, killing approximately 2,000 people and injuring 9,000. Twenty-five thousand were left without shelter. Debris was scattered over three miles away, and windows shattered up to 60 miles away, blinding many.

Most cities are divided between class and race, and Halifax, with a population at the time of about 60,000, was no different. The north end of the city, where factories and businesses dominated the landscape, was leveled. Many neighborhoods were destroyed. Africville, where American blacks had long settled, including some who had escaped slavery during the War of 1812, was considerably damaged but not destroyed*. The dock and rail yards and the working-class community of Richmond, where once stood the Acadia Sugar Refinery and the Richmond Printing Company, were obliterated. But no part of Halifax escaped without damage.

The explosion was so powerful, it literally blew the water out of the Narrows. The resulting tsunami in the aftershock, exposing the harbor floor, further laid waste to the shores of Halifax and Dartmouth. The location of the explosion within the Narrows and the topography of the harbor made the resulting tidal wave worse. The ancient Mi’kmaq settlement of Turtle Grove was finished off with the wave of water. Many, still stunned by the explosion, were drowned. Yet another cruel blow was to come the next day when a blizzard blanketed the area, hampering relief efforts as snow covered the dead and dying.

In Halifax’s Fairview Cemetery is a small memorial to the Great Explosion. Many of the dead rest there, as do some of the victims of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, five years earlier. The city had acted as the center of relief and recovery efforts in that tragedy. It was experienced in setting up temporary morgues and re-implemented the system developed in 1912 for numbering and identifying bodies in a disaster.

Seismic records registering the time of the blast have only recently been recovered, as well as some first-hand accounts. Other poignant reminders of the city that was, and what happened to it are in archives and libraries, documenting the experience of the place a hundred years ago, and the world’s largest accidental man-made explosion to this day.

Notes and Further Reading

“Establishing Blame in the Halifax Explosion” CBC Digital Archives.

Smithsonian Institution. “A Century-Old Boston Christmas Tree Tradition Costs Canadians Big Money.” But it is a touching reminder of the tragedy and the world-wide response in providing relief to the devastated Halifax.

“From One Moment to the Next: The Halifax Explosion” University of Virginia online exhibition

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, The Halifax Explosion

“Halifax Explosion 100 Years 100 Stories”

*Corrected 4/3/20. Post previously asserted that Africville was completely destroyed. See “Racism and Relief Distribution in the Aftermath of the Halifax Explosion” (2019) by Mark Culligan and Katrin MacPhee for more information.

4 Comments

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax has an informative and mournful exhibit on the explosion. It does a very good job of telling several kinds of stories. One is the more clinical side of the event — the strength of the explosion, for example. Another would be the large numbers — those killed, wounded, displaced. And then also, the displays tell of the individuals, like Vince Coleman, train dispatcher. He stayed to warn off other trains and paid with his life. In the display are his wallet, with lottery ticket, and the very telegraph key he used. It was a moving exhibit to say the least.

Brett,

Thank you so much for this information. The Maritime Museum has wonderful online resources about the Explosion. But I would very much like to visit the institution in person. As you indicate, the poignancy of the actual artifacts must be almost overwhelming.

Julia

prof premraj pushpakaran writes — 2017 marks the 100 years since Halifax disaster!!!

“Barometer Rising”, a historical fiction novel based around the Halifax explosion was required reading in my Canadian high school: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barometer_Rising