“Do your reading!” and “Don’t write in your books!” are two oft-echoed directions from schoolteachers. A 1491 edition of Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia housed in our Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History, however, challenges both of those commands: not only did Pliny write it in such a way that doesn’t necessitate reading it cover to cover, but readers in centuries past have added notes, reactions, and even corrections to every page of the book! These reader-made notes and symbols are known as marginalia, and in this copy of the Historia, many of them were made in order to make navigating the text as efficient as possible. But the density and the variety of marginalia indicates that at least eight different annotators have added their thoughts to the Cullman’s copy over the course of several centuries. Unfortunately, due to the loss of evidence resulting from the Historia’s rebinding, their identities and relationship to the book remain vague. But understanding—and, in some cases, not understanding—what these annotators were hoping to accomplish in their note-taking offers us some clues to who they were and how they used the book. This, in conjunction with understanding how Pliny intended the Historia to be used, illuminates a period when people didn’t just read books—they interacted with them.

Readers of a certain age may recall visiting their school library in the course of writing a research paper or book report, and making their first stop the long shelf that held the multitudinous volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica. For centuries, the thirty-seven books of the Historia served the same function for scholars. In his dedication to the future Roman emperor Titus, Pliny states that his work describes “the nature of things, and life as it actually exists,” and that although “there still remain many things which [he has] omitted,” he hopes that in it he has “treat[ed] all of those things… which are either not generally known or are rendered dubious from our ingenious conceits.”[1]

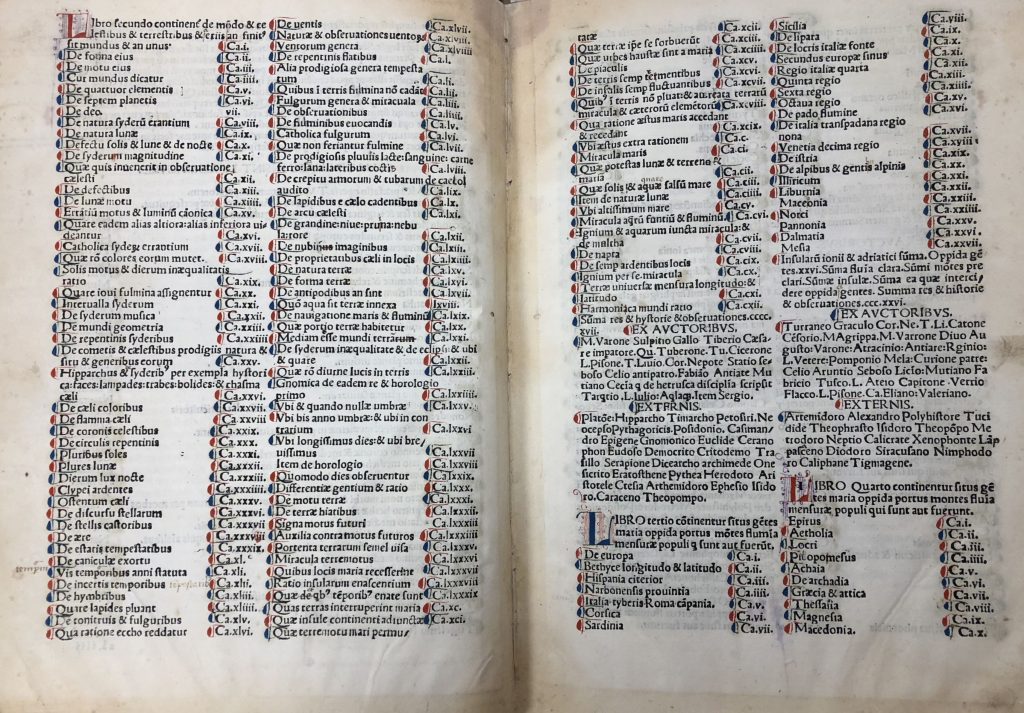

In most ways other than its name, the Historia is the first attempt at creating an encyclopedia in the western world—it aspires to be a comprehensive summary of knowledge about a particular subject, organized into easily-navigable headings which are laid out in the summarium (a sort of proto-index) at the beginning of the work. That Pliny made an effort at predicting the research interests of his readers was just short of revolutionary in 79 AD, when the Historia was first “published.”[2] In fact, he even pokes fun at this fact in his dedication: he states that he included the summarium “so you [Titus] don’t have to go to the trouble of reading [all thirty-seven books]. And so you will have provided everyone else with the means not to read it through either, instead everyone will look for the particular thing they want and know where to find it.”[3] But even with all this thinking ahead, the Historia couldn’t please everyone.

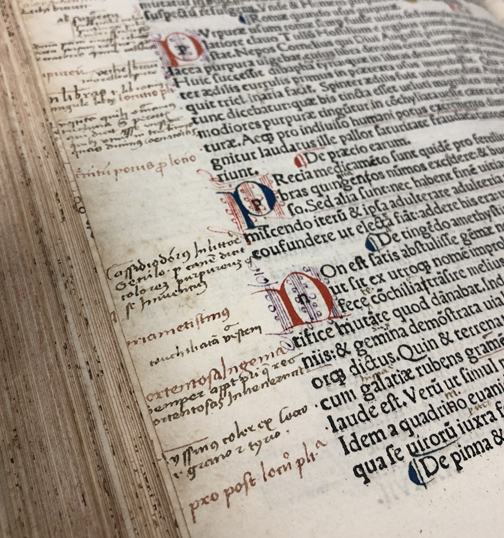

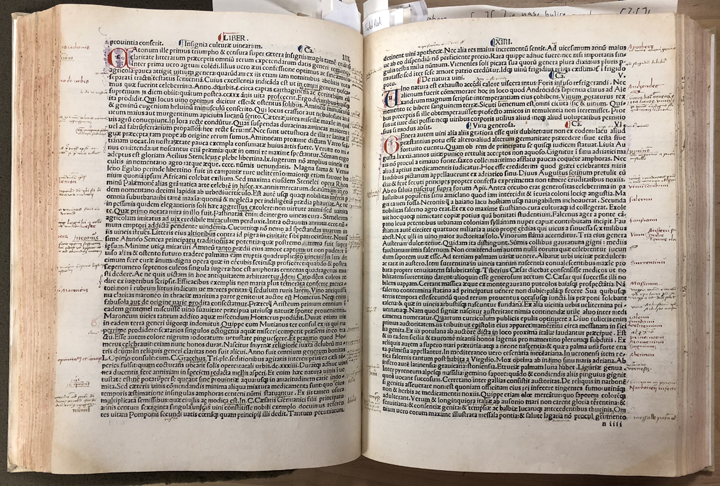

In centuries past, attitudes toward books were quite different, both on the part of the author and the reader. Rather than a disruption of authorial intent, these reader additions were seen as part of a collaboration over time, resulting in “the production of the best text.”[4] Not all marginalia had such a noble aim—many examples of doodles and daydreaming in the margins have also survived[5]—but in the Cullman’s Historia, the vast majority of the reader-added marks are indeed meant to augment the text in some way, whether that means making it easier to navigate in regard to their individual interests or adding more details about certain subjects.

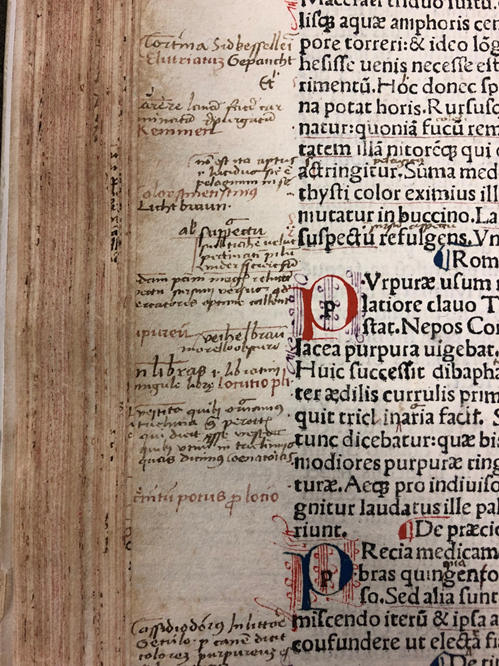

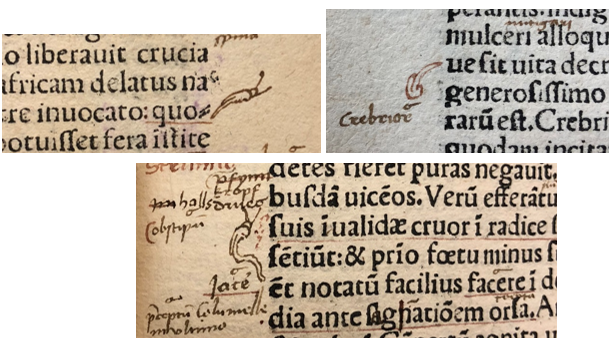

Each annotator seems to have had their own agenda for their note-making, which shows up in the form and content of their marginalia; this, along with their handwriting and the different inks they used, leads me to surmise that there were eight or more of them. Despite the differences in their marginal styles that make them identifiable as discrete individuals, they employ similar methods of note-making and drawing attention to relevant passages. Manicules (Latin for “little hands”) and other symbols of a variety of styles pop up throughout the Historia, and are used in almost the same way that readers use sticky flags in their books today.

Underlining and placing passages in brackets also served to highlight items that the annotators saw to be important, or that they wished to discuss further in a longer marginal note. The fact that, based on their styles of handwriting, they were all making notes in the book between around 1500 and 1700 does much to explain the similarities. In that period, learning to read came part and parcel with learning methods of annotation; historian William H. Sherman describes how “reading used to be considered as much the province of the hand as of the other faculties,”[6] and it is clear that the annotators of the Historia were not shy about putting pen to paper.

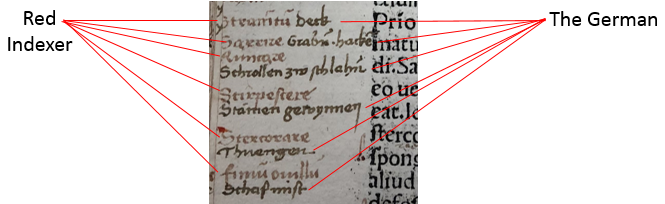

The nature and content of the marginal notes, indexes, and glosses are what really establish the different annotators as individuals. Although their identities remain unclear at best, they reveal themselves in what they chose to make note of and how they do it; this information has been used to give them nicknames that, while not terribly creative, serve to trace their actions through the text. For example, the Red Indexer acts exactly as their nickname implies: they have thoroughly indexed the book, pulling out more granular subject headings that are not mentioned in the chapter titles. Following in the Red Indexer’s footsteps is the German, who glosses many—but not all—of the index words as their German equivalent. Understanding that the German glossed the Red Indexer, rather than vice versa, situates the German after the Red Indexer on a time line. Two other annotators, Faded Red and Sloppy Hand, act as beginning and end points of this timeline: Faded Red’s notes are situated at the extreme edges of the page and have, in some cases, been trimmed away when the book was rebound, while the style of the Sloppy Hand indicates that the annotator was probably working in the early 18th century.

The nature and content of the marginal notes, indexes, and glosses are what really establish the different annotators as individuals. Although their identities remain unclear at best, they reveal themselves in what they chose to make note of and how they do it; this information has been used to give them nicknames that, while not terribly creative, serve to trace their actions through the text. For example, the Red Indexer acts exactly as their nickname implies: they have thoroughly indexed the book, pulling out more granular subject headings that are not mentioned in the chapter titles. Following in the Red Indexer’s footsteps is the German, who glosses many—but not all—of the index words as their German equivalent. Understanding that the German glossed the Red Indexer, rather than vice versa, situates the German after the Red Indexer on a time line. Two other annotators, Faded Red and Sloppy Hand, act as beginning and end points of this timeline: Faded Red’s notes are situated at the extreme edges of the page and have, in some cases, been trimmed away when the book was rebound, while the style of the Sloppy Hand indicates that the annotator was probably working in the early 18th century.

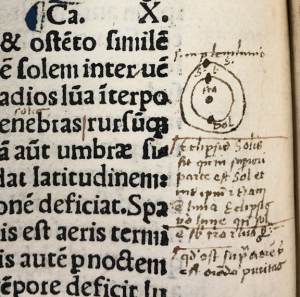

Four other annotators occupy the rest of the timeline, but two in particular stand out: Bracket and the Editor. Bracket is responsible for the longest marginal notes, which run the gamut from cross-referencing other works that Pliny has cited, to adding detail about subjects mentioned, and even to drawing diagrams of concepts that Pliny describes. This annotator tends to enclose one side of these notes in a bracket that points back towards the passage being referenced—hence the name. The Editor’s name is self-explanatory too: they have peppered every page of the text with spelling corrections, some

of which are so small that they are barely visible.

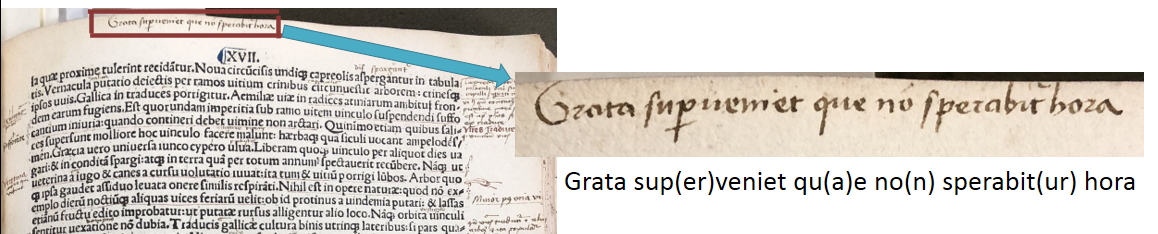

But what is interesting about these two annotators is not what we understand about them, but what we do not. Bracket is responsible for the most befuddling note in the text: a grim line from Horace’s Epistles, which when translated reads “the unhoped for hour will be a welcome surprise.”

This is in reference to the inevitability and acceptance of death, which is a heavy topic to refer to in the margin of a chapter about caring for grapes and the diseases of trees. Pliny does not even reference Horace in this chapter, which rules out Bracket’s usual practice of cross-referencing sources. Although its purpose remains mysterious, the fact that Bracket included it gives us a glimpse of other works that they may have been reading at the time, which in turn bolsters our understanding of what texts were available to and being used by literate people.

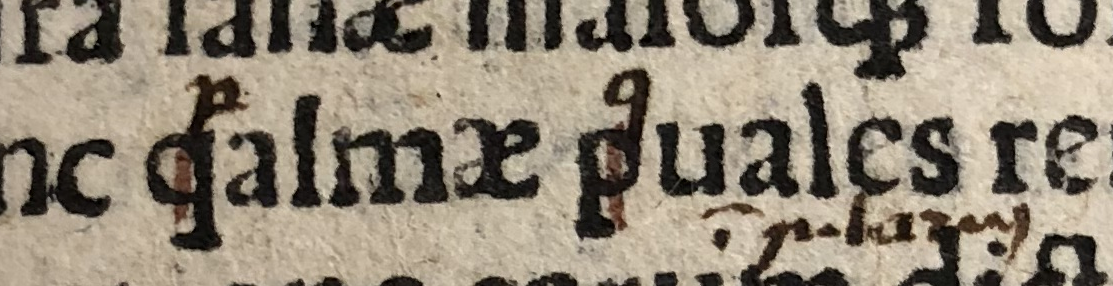

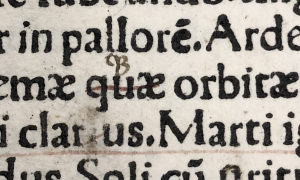

The Editor’s goal, which at first seems relatively clear, is in fact nearly as ambiguous as Bracket’s reference to Horace: what is the point of being so thorough in making corrections to the text, aside from pedantry? The Cullman’s copy of the Historia was clearly not a working copy, which would have been used for editing purposes in the printing process—the fact that the text is embellished with colorful, hand-finished initials indicates that it was in fact a top-of-the-line book, and not something to be corrected and discarded on the print shop floor. One correction, though, points to preparation rather than pedantry: a simple suggestion of using an abbreviation rather than the full Latin word quae. It is possible that the Editor was using the Cullman’s Historia to prepare a new edition of the work sometime in the 16th or 17th centuries, and the multitudinous corrections represent their efforts to iron out any mistakes made in this 1491 edition. The suggestion of an abbreviation amongst numerous spelling corrections points to a person who is concerned not only with accurate spelling, but with brevity. Comparing the corrections in this copy to later editions may reinforce this theory, although since the Historia has only rarely been out of print since the 15th century, there will be a lot of material to work through.

The Editor’s goal, which at first seems relatively clear, is in fact nearly as ambiguous as Bracket’s reference to Horace: what is the point of being so thorough in making corrections to the text, aside from pedantry? The Cullman’s copy of the Historia was clearly not a working copy, which would have been used for editing purposes in the printing process—the fact that the text is embellished with colorful, hand-finished initials indicates that it was in fact a top-of-the-line book, and not something to be corrected and discarded on the print shop floor. One correction, though, points to preparation rather than pedantry: a simple suggestion of using an abbreviation rather than the full Latin word quae. It is possible that the Editor was using the Cullman’s Historia to prepare a new edition of the work sometime in the 16th or 17th centuries, and the multitudinous corrections represent their efforts to iron out any mistakes made in this 1491 edition. The suggestion of an abbreviation amongst numerous spelling corrections points to a person who is concerned not only with accurate spelling, but with brevity. Comparing the corrections in this copy to later editions may reinforce this theory, although since the Historia has only rarely been out of print since the 15th century, there will be a lot of material to work through.

Unfortunately, we may never be certain of why the Cullman’s Historia was annotated by so many different people. As it has been rebound at least twice, it has lost a great deal of provenance information, such as bookplates, shelfmarks, or ownership inscriptions. This is one of the reasons why historians treasure marginalia: not only does it reflect the knowledge and interests of the readers making it, it adds precious detail to this book’s individual history. And while we might not know the annotators’ names, their marks, notes, and corrections reveal so much more about them as people than a simple ownership inscription would. Continued research will enable this book, and its annotators, to tell even more of its story. Luckily, future generations of scholars will be able to study the volume from anywhere in the world, via a digitized copy in the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

[1] Naturalis Historia, Book 1.

[2] Published in quotation marks here because moveable type would not be a presence in Europe for another 1400 years—in 79 AD, publication meant that exemplary scrolls were released to the public for borrowing and copying.

[3] Naturalis Historia, Book 1.

[4] Whitaker, Elaine E. “A Collaboration of Readers: Categorization of the Annotations in Copies of Caxton’s Royal Book 234.” Text Volume 7. (1994): 233-242. P. 234.

[5] Johanna Green has written and spoken widely about University of Glasgow MS Hunter 232 (U.3.5), a 15th century manuscript full of doodles, as mentioned in this 2017 Atlas Obscura article; closer to home, the Cullman’s own 1598 Discours of Voyages is packed with penmanship practice and various scribbles.

[6] Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, p.23

3 Comments

This is extremely fascinating! Thanks for the wonderful post!

[…] This post is derived from an article published on the Smithsonian Libraries’ blog. View the original post. […]

I just found Allie’s blogs here and I can tell it’s going to be some good reading! The blogs are so well written and researched. This one was really fascinating. I’m sure The Editor, was indeed editing a future edition.