This blog post was written by G. Goldberg, student at Smith College and Summer 2019 intern in the Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex.

Interning at the Smithsonian Libraries Research Annex (SLRA) on the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) Research Collection has been, as my college advisor says, a “plum” of an experience.

This is especially because many of the books that my fellow intern, Mikaela Hamilton, and I have been pre-processing for eventual cataloguing have been the “plums” of the collection. When packing books to send to the Annex, CFCH divided them into categories. These included circulating volumes shared via check-out and interlibrary loan, and non-circulating volumes to be viewed in-house only. Interns that came before us processed most of the former category, so by the time Mikaela and I arrived in June, there were only two boxes left to process of those. Then we moved on to the “non-circulating collections,” those that the CFCH determined valuable enough to restrict use. Determination of value comes from multiple factors, including provenance (did someone important own it and/or sign it?), relevance (do researchers continually request it?) and rarity (is it old and/or scarce?). This meant we were guaranteed some of the most fascinating pieces.

The collection focuses on exactly what it says, “Folklife and Cultural Heritage,” nationally and internationally. This means lots of traditional music and dance, oral and written story tradition, folk art, and festival and religious tradition. Most of the collection is focused on American folklife across the country, but it also stretches across the globe. The collection does not just organize itself geographically. It also organizes itself by race, ethnicity, and other cultural delineations.

As a Jewish American, my interest was piqued when I processed books concerning Jewish culture. My wonderful supervisor, Daria Wingreen-Mason, encouraged us to explore little curiosities, but as it came time to think about content for this post, I decided to look more deeply at those pieces.

I kept in mind questions concerning how Judaism fits into “Folklife and Cultural Heritage.” It is a topic I have thought about and discussed frequently with my family and friends, though without that verbiage. There is confusion about the categorization of Judaism. It is a religion, but also more. Hitler and others have referred to it as the Jewish Race, which is highly problematic. Some call it an Ethno-Religion, but that term gives me pause. There is a sect of Judaism– Secular Humanist– which is an atheist sect that finds Judaism’s value in its culture, tradition, heritage, and history.

Therefore, my blog post is my exploration of where Jewishness fits into the idea of “Folklife and Cultural Heritage” by investigating some of the pieces in the CFCH Research Collection.

I began by exploring some of the mentions of Judaism in broader anthologies or surveys. Most of these were written by non-Jews. The majority of them clearly did not consult any actual Jews. Several merely had one sentence or paragraph. Never did I find the words “nigune,” (wordless Jewish melodies), or “Klezmer” (a genre of Eastern European Jewish folk music). Some books, such as Folklore in America, were quite respectful, if brief. I typically found these titles had at least one distinctly Jewish among their editors.

I then turned my attention to titles pertaining specifically to Jewish subjects.

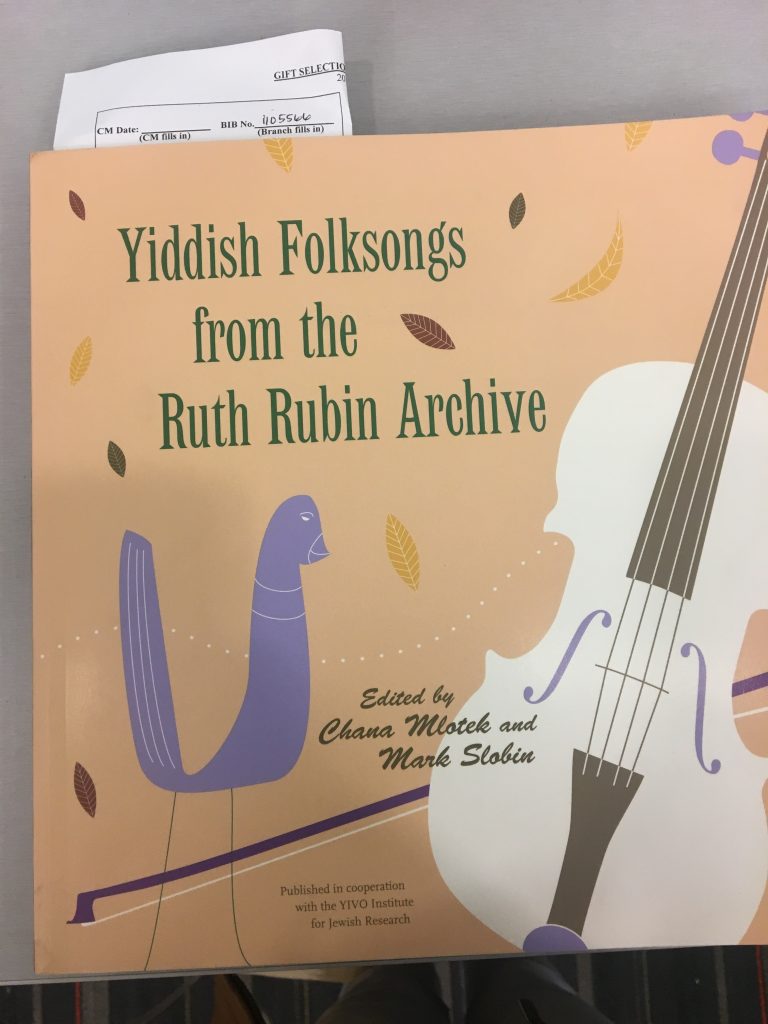

Some inclusions focus on ‘folklife.’ An example is Yiddish Folksongs from the Ruth Rubin Archive. This was the only place I saw the word ‘nigune.’ (That said, I did not read the books cover to cover.) This book focuses on folksong, precisely the mission of the collection. It discusses preserving a fading culture that is part of many Jews’ heritage.

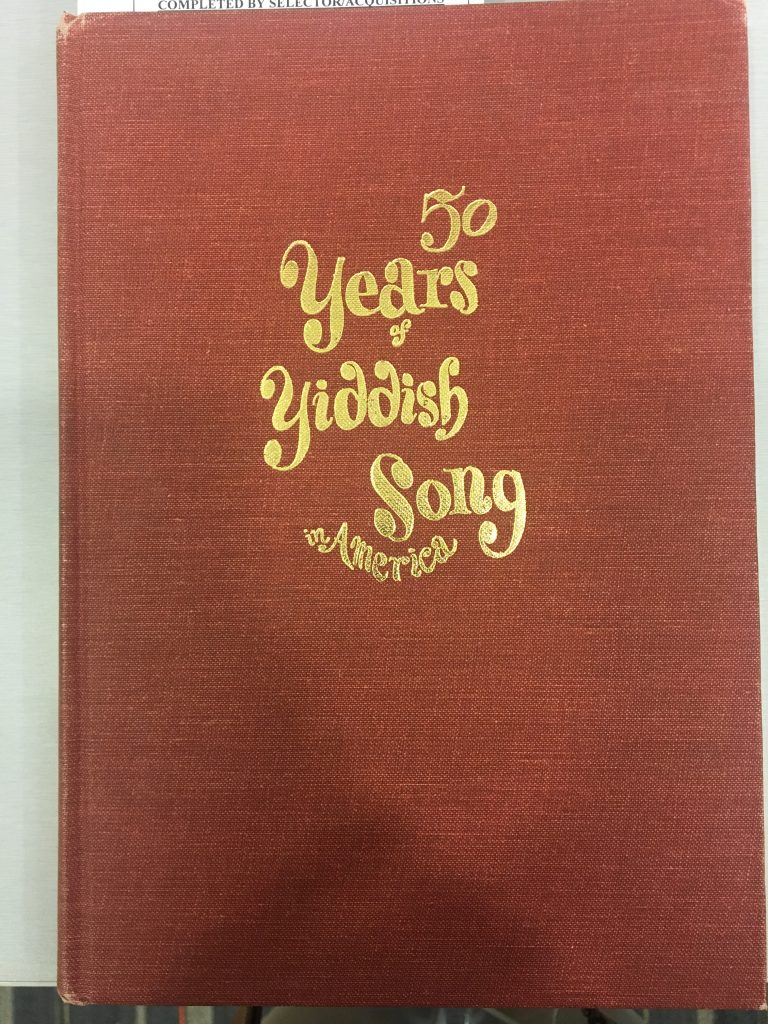

Other titles were broader. 50 Years of Yiddish Song in America includes folk but also religious songs. It uses “Jewish folksong” and “Yiddish folksong” interchangeably, which is a narrow view of Jewish culture. Not all American Jews are descendants of Yiddish speakers.

A book that acknowledged this was The Jews of Kurdistan, an anthropological survey. The acknowledgement that there are Jews in the Middle East (outside Israel) and Asia is important and underappreciated. It may seem small, but I am extremely happy to see this book as part of the collection.

Another title I appreciated the broadness of was Because Gd Loves Stories : An Anthology of Jewish Storytelling [1] . This was a collection of stories under several headings, including “Ancient Times in Contemporary Tales,” “The Immigrant Experience,” “The Holocaust,” and “The Lower East Side and Beyond.” That last included the subheadings, “Tenement Life, “The American South,” “The Catskills,” “Yiddish Theater,” and “Jewish Summer Camps.” This book recognizes that ‘folk story’ comes out of historical times of hardship but also positive Jewish experiences, like summer camp. Many an American Jew have bonded over shared or similar summer camp experiences, most happy, some less so. It also acknowledges that the Holocaust does not define us, but it has an impact that demands to be recognized. (The Crazy Ex-Girlfriend song “Remember That We Suffered,” anyone?)

A book focusing on that topic is Singing for Survival : Songs of the Lodz Ghetto, 1940-1945. My first impressions were that this was a heavy topic to be included in this collection. One’s mind (at least, my mind), when hearing the term folk music, thinks of somewhat upbeat songs on twangy guitars in the American west (think: Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger), which does constitute a large part of the collection (there is so much Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger). The preface explains that the book “is an attempt to understand the role of singing in times of duress.” This made me think back to other facets of our collection, such as the wide representation of spirituals (particularly black/enslaved peoples’ spirituals) (though the collection also includes ‘white spirituals’ which—what??) and also the plethora of material on protest songs and civil rights movements. That made this book’s inclusion make more sense. Folk music is created by and for the common folk, particularly the downtrodden. And the deepness of the tragedy that catalyzes the production of such music is irrelevant. We may associate folk music with poor farmers in the south, or songs of peace and love during the 60s, but deadlier tragedies provide the same type of conditions that lead to the creation of art, only in a more grievous manner.

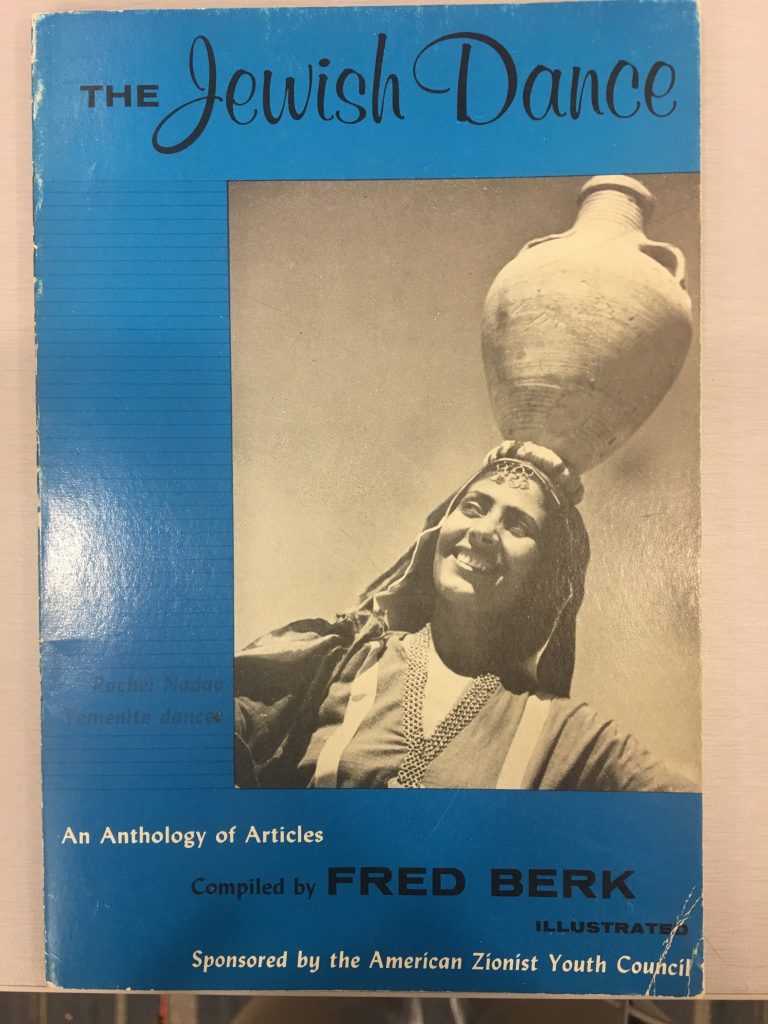

The other side of this coin is music created during times of peace and prosperity. The Jewish Dance : An Anthology of Articles represents a very different form of creation than that which comes out of periods of oppression. It focuses mostly on modern Israeli dance, though it does give context. This is not emanating from a cry for freedom but the celebration of it. This is “an authentic Jewish dance form created by a free people on their own soil pursuing their own creative impulses.” That said, it was not born in a vacuum; it “traces its beginnings and ramifications throughout Jewish history.” That is to say, Jewish music and dance created under duress deeply influences the way it evolves in times of joy.

The Jewish-related books span a wide gamut of Jewish art and culture, and though they only constitute a small part of the collection, they ultimately paint an important picture. Seeing the variety and the complicated history reminds me how resilient Jewish culture has been through the centuries, and makes me proud to be a part of it.

I have had an incredible experience this summer processing the CFCH Research Collection. There were so many fascinating finds, and I learned so much. Jewish titles were far from the only objects of interest, but as it is a subject close to my heart, I appreciated the opportunity to take a closer look. I would like to thank my fellow intern Mikaela Hamilton, my supervisor Daria Wingreen-Mason, and the SLRA Library Technician Alan Katz. Additional shout-outs to my main men Ralph Rinzler and Moe Asch (their names popped up extremely frequently as previous owner signatures), as well as Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger (I cannot stress enough how much Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger there is).

[1] I choose not to type out the word Gd in my article, a choice many Jews make due to the directive never to destroy Gd’s name. In the book, the word is spelled out.

Be First to Comment