Morgan E. Aronson has recently departed the Smithsonian Libraries but was previously the library technician at the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology.

The role of the rubricator in early printed texts is often curtailed to that of a useful book decorator, a person with red (and sometimes blue) ink who guides the book’s reader with helpful indicators like colored initials, paragraph marks, initial-strokes, and underlining. Each individual who undertook the responsibility of rubrication often interpreted their duty differently, leaving a unique canon of rubrication for scholars to interpret. Though traditional types of rubrication have been studied, this short analysis of one text will bring to light a rubricator engaging with the text beyond the rubricator’s traditional scope.

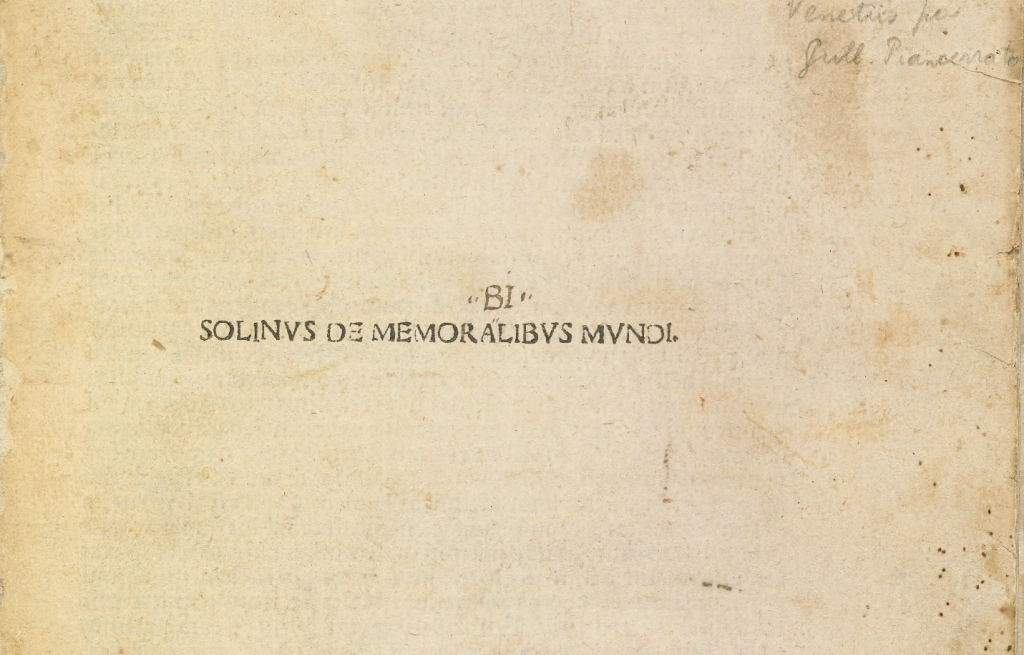

One aspect of rubrication upon which most scholars agree is that rubrication developed as an aid to the reader, as a way to articulate the text—creating a hierarchical system of signals within the book to reveal an otherwise buried textual structure. But what happens when we find a pattern of rubrication that doesn’t quite fit even this broad generalization of the role? The Smithsonian Libraries’ Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology holds a 1493 copy of Solinus’ De memora[bi]libus mundi. Though not a very rare text in itself, this copy features a rare style of “reader-rubrication” which stretches the boundaries of the traditional interpretation of the role to the point where the line between rubricator and reader becomes blurred.

Solinus’ Polyhistor

Solinus was a mid-third century compiler who used materials from many sources, including Pliny’s Natural History, when writing this, his most well-known work. De memora[bi]libus mundi, better known under its title of Polyhistor, is a collection of memorable things in world history, with sections related to geography, historical events, religion, customs, and even natural history. This copy was printed in 1493, meaning it can be categorized as an incunabulum (from the infancy of printing, prior to 1501). Rubrication in incunabula is less often studied than in manuscripts, but scholars like Margaret M. Smith have made great strides in developing an understanding of the function of rubrication during this chaotic time in the history of print. While manuscript scribes often left notes, in the form of annotations, to the rubricator in a book’s margin, that form of communication is less practical once the scribe is replaced by a printing press. There were attempts by early printers to also mechanize rubrication, and Smith explains this effort underlines the importance of rubrication even in the age of early print. But the cost and difficulty of mechanized rubrication meant that hand rubrication was still prioritized until the late 15th century. Still, in the early era of print, with punctuation and finding apparatus not always prioritized by the printer, there was still ample opportunity for scribal interpretive intervention.

Traditional and Non-Traditional Rubrication

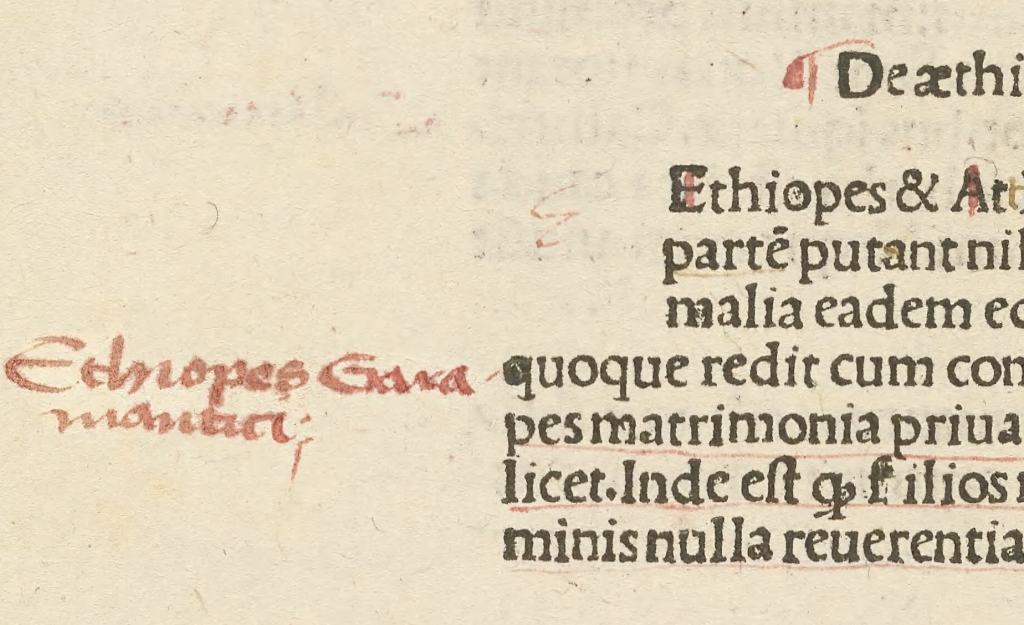

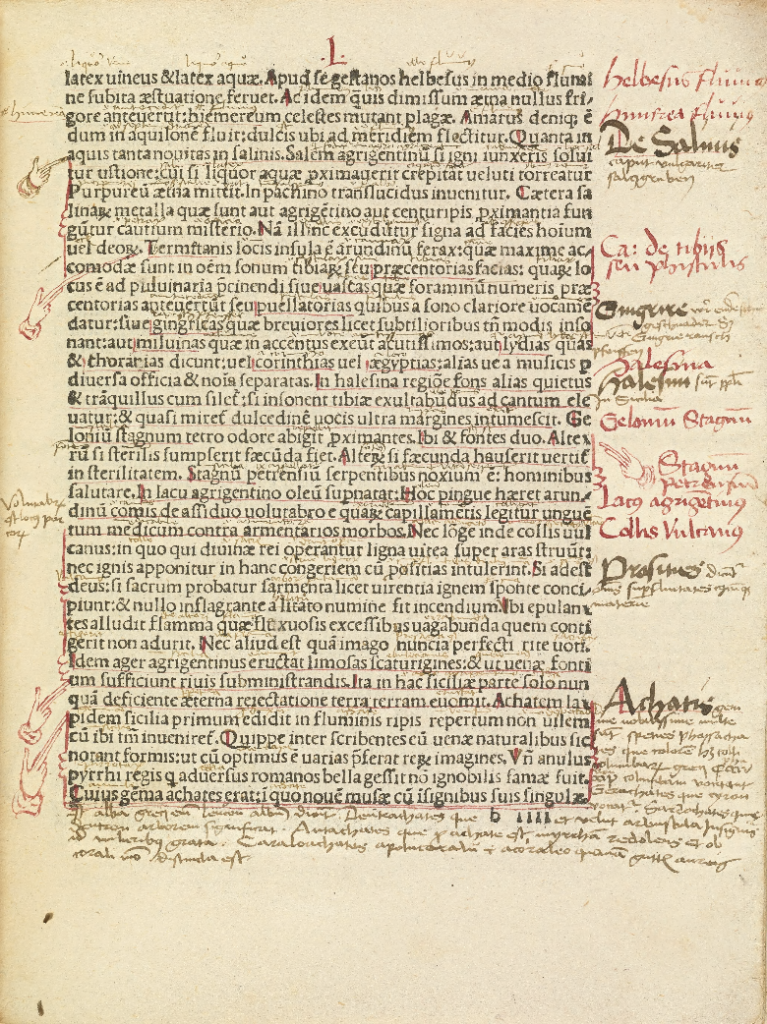

Smith identifies the principle manifestations of rubrication as enlarged initials, paragraph marks, initial-strokes, and underlining. Most of these are evident in De memora[bi]libus. Red paragraph marks are most common before chapter headings, but can also be seen within text blocks designating new sections. The initial-stroke, a line of red ink through a capital letter, is ubiquitous, appearing in large numbers of every page. These traditional uses of rubrication help us to identify the process of rubrication occurring beyond simply the use of red ink.

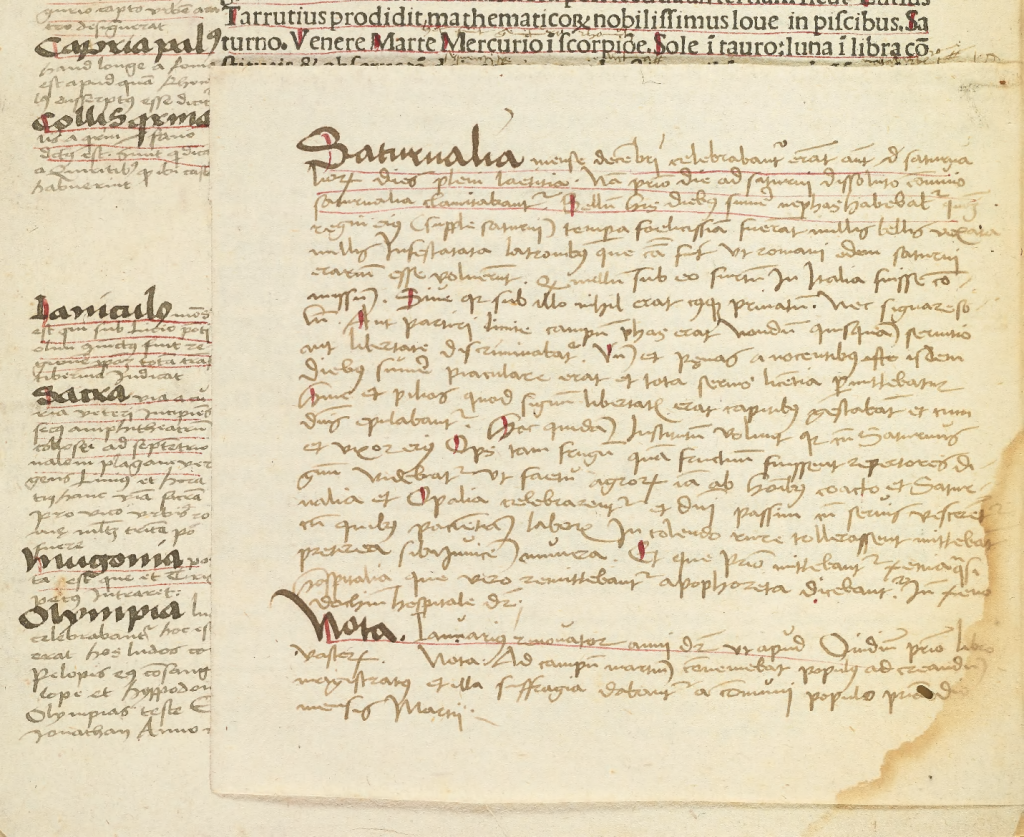

In addition to the rubrication, this is a heavily annotated text. The active reader, or annotator, represented by the dark ink, should not be conflated with the rubricator. The annotator took on few of the traditional rubric functions, choosing to add to the text rather than explain its structure. The writing in dark ink appears both in the margins and in-between lines of text and mostly consists of larger heading-style words that relate to a point in the text, like a place name, and small notes underneath and within the text. It is clear that two distinct hands completed the two separate functions of annotating and rubricating. There are obvious stylistic differences in the hand, with the capital letter D an especially clear indication. With the identity of the rubricator now made distinctly separate from the annotator, it is possible to delve deeper into the unusual style of reader-rubrication seen in this text.

Manicules and Inclusive Marks

The evidence collected from this special incunabula creates a narrative of a very different type of rubricator than those typically discussed. This rubricator was a reader, and not this book’s first. The purpose of the rubrication was not solely to enable a better reading of the text, but also to facilitate understanding of even the annotations previously written within. The purpose of the rubrication in this case was certainly not decorative, nor solely guiding. The rubrication was neither performed by a professional scribe or rubricator before the purchase of the book’s pages, as can be seen from the rubricated tipped in leaf, nor was it absolutely necessary to the correct interpretation of the text, based on the older annotations. Even more compelling is the unique style of rubrication that reveals a very clear interaction with the text, the drawing of 45 manicules (pointing hands) in 102 pages, going far beyond the work of a useful book decorator to show a true engagement with the book’s content.

Be First to Comment