What products or materials come to mind when you think of libraries? The obvious things might be books and shelving, but to keep a library functioning other items are needed as well. Supplies for circulating and tracking books and identifying ownership of books remain largely behind the scenes but are just as important.

Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau (1899) by Library Bureau is a trade catalog providing us a glimpse into supplies and equipment that library staff in 1899 might have used to complete their everyday tasks. Though much has changed, we might recognize some basic concepts that still exist.

Today we use a library borrower’s card to check out a book. Typically, each book has a barcode that assists library staff in circulating and tracking that particular book via an online library system. We might also notice a property stamp inside the book. The property stamp identifies the library that owns the book. What supplies did libraries in 1899 use to circulate and identify their materials?

As highlighted in a previous post, paper-based charging systems were used to circulate books before the availability of computers and online library systems. Both types of systems require borrower’s cards, but paper-based charging systems also require a book card or charging card for each book.

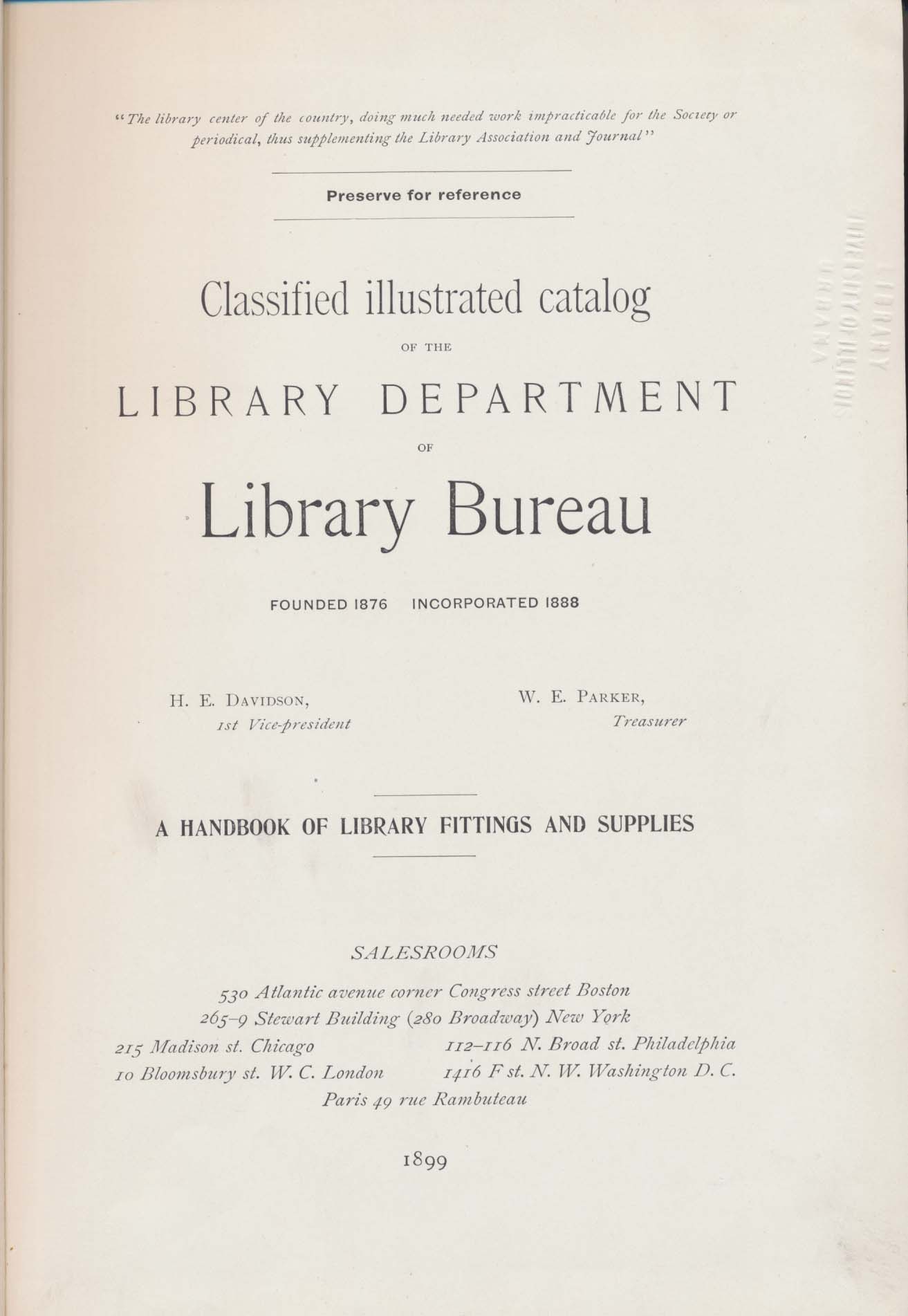

An example of a borrower’s card from 1899 is shown below. The top portion included general information pertaining to the user such as name and address. It also included the Borrower’s Pledge. A version of this pledge might sound familiar to us today. As in the example below, library borrowers pledged to be responsible for all materials charged to them. The bottom portion of the card included ruled lines for noting borrowed books and dates for when each book was borrowed and returned.

When a paper-based charging system is used, a charging card, or book card, for each book is also necessary. An example of a charging card from 1899 is shown below. It included ruled lines on both the front and back to record information about the book. The three lines at the top were intended for entering the title and author of the book and its number, what we typically refer to as a call number today. Below that section were more ruled lines or small boxes. Each time the book was checked out and returned, library staff recorded such things as borrowing date and returned date in those small boxes. This provided a history of the book’s circulation.

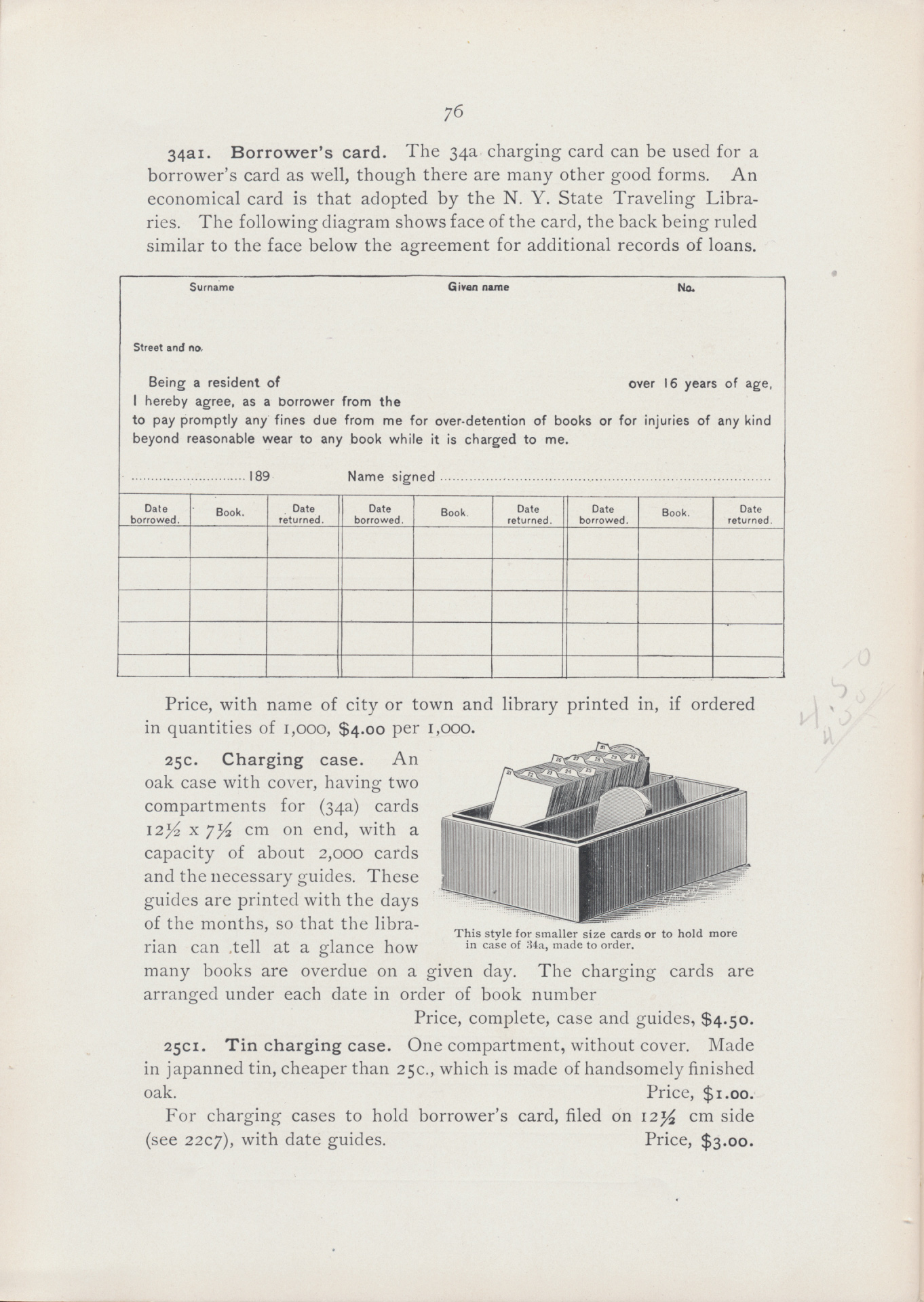

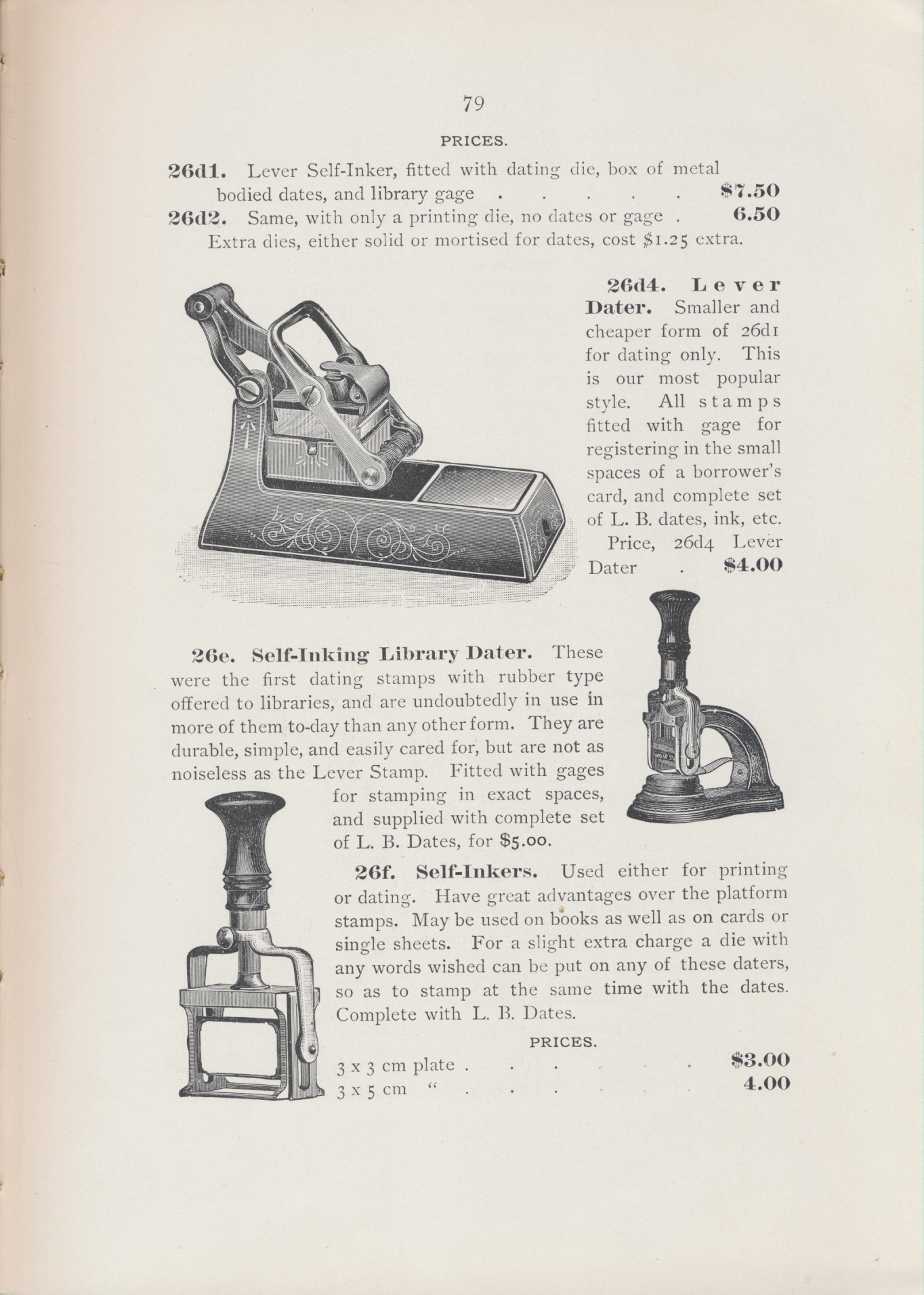

To record those dates on the cards, library staff might have used the Self-Inking Library Dater illustrated below (middle right) or the Lever Dater also shown below (top left). Both had the ability to stamp dates in tiny spaces on cards. According to this 1899 trade catalog, the Lever Dater was Library Bureau’s “most popular style” at the time. A drawback of the Self-Inking Library Dater might have been that it was not as noiseless as the Lever Stamp.

Dates were just one piece of information for which libraries might have used a stamp. The Self-Inker (below, bottom left) was another handy tool because it was customizable and capable of stamping both dates and words. Due to its design, another feature was its ability to stamp not only cards or single sheets of paper but also books.

Just like today, libraries in 1899 needed a way to mark ownership to assist in identifying their books. Today we might notice a property stamp inside a book stating the name of the library that owns it. In 1899, an option for marking ownership was the Perforating Stamp. As shown below, this type of stamp perforated the page by spelling out the name of the library with perforation marks. It was described as an alternative to the embossing stamp and did not increase the thickness of the book.

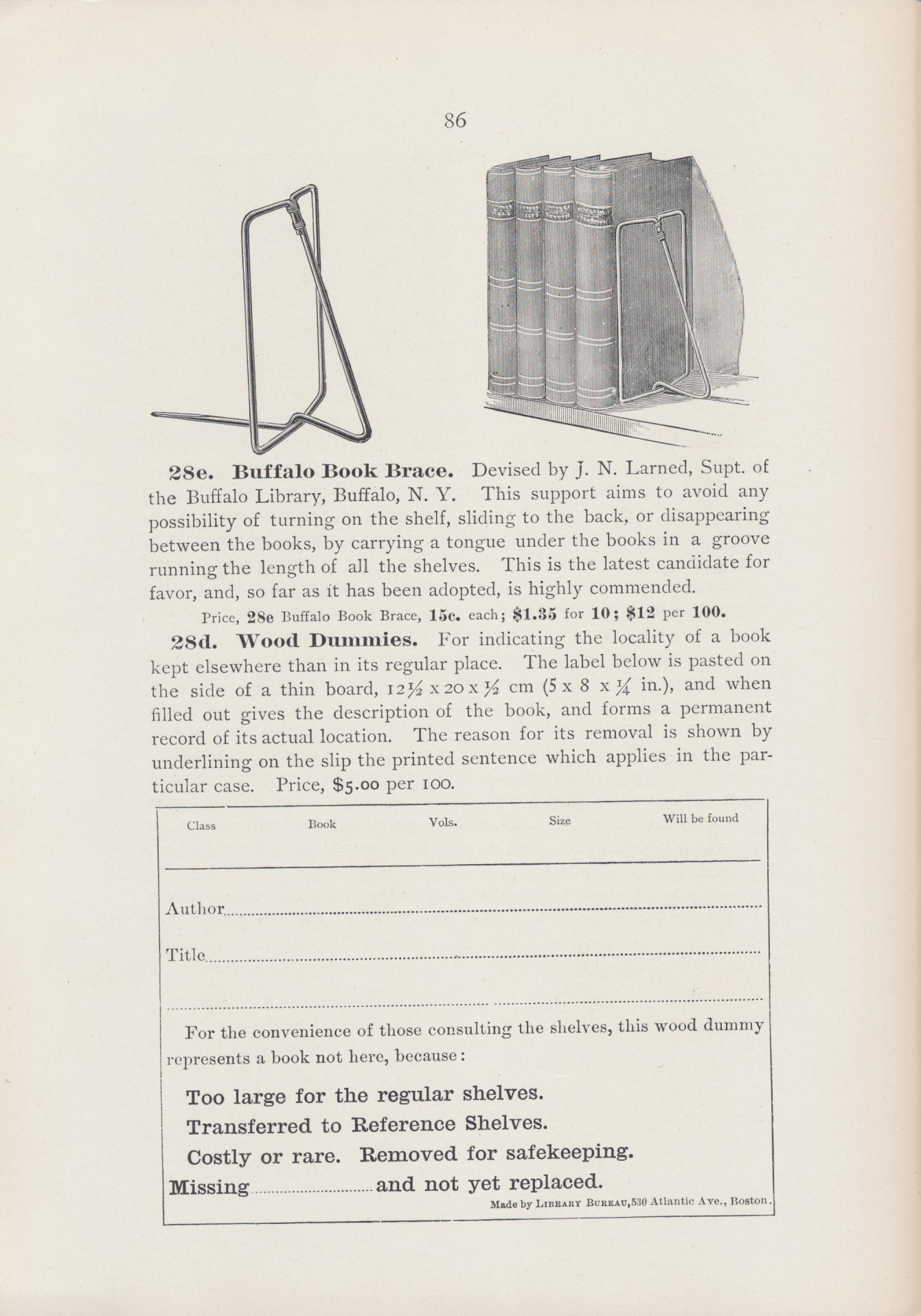

Now let’s take a closer look at equipment that might be useful when shelving or browsing the stacks. Every so often, library staff may come across a book that is too large to be safely shelved in its proper location. The book is typically removed and shelved in a more suitable spot based on its size. Judging from supplies offered in this trade catalog, the same thing happened in 1899.

To assist in locating an oversize book in its new location, Library Bureau offered supplies called “Wood Dummies.” These were thin boards measuring 5 x 8 x 1/4 inches and meant to be shelved in the book’s proper, or original, location. A label, such as the one below, was attached to the board to assist users in locating the book’s actual location. The label included bibliographic information and the book’s new location along with the reason for it being moved. This particular label gives several reasons. Besides being “too large for the regular shelves,” other reasons included rarity, cost, being transferred to Reference, or missing.

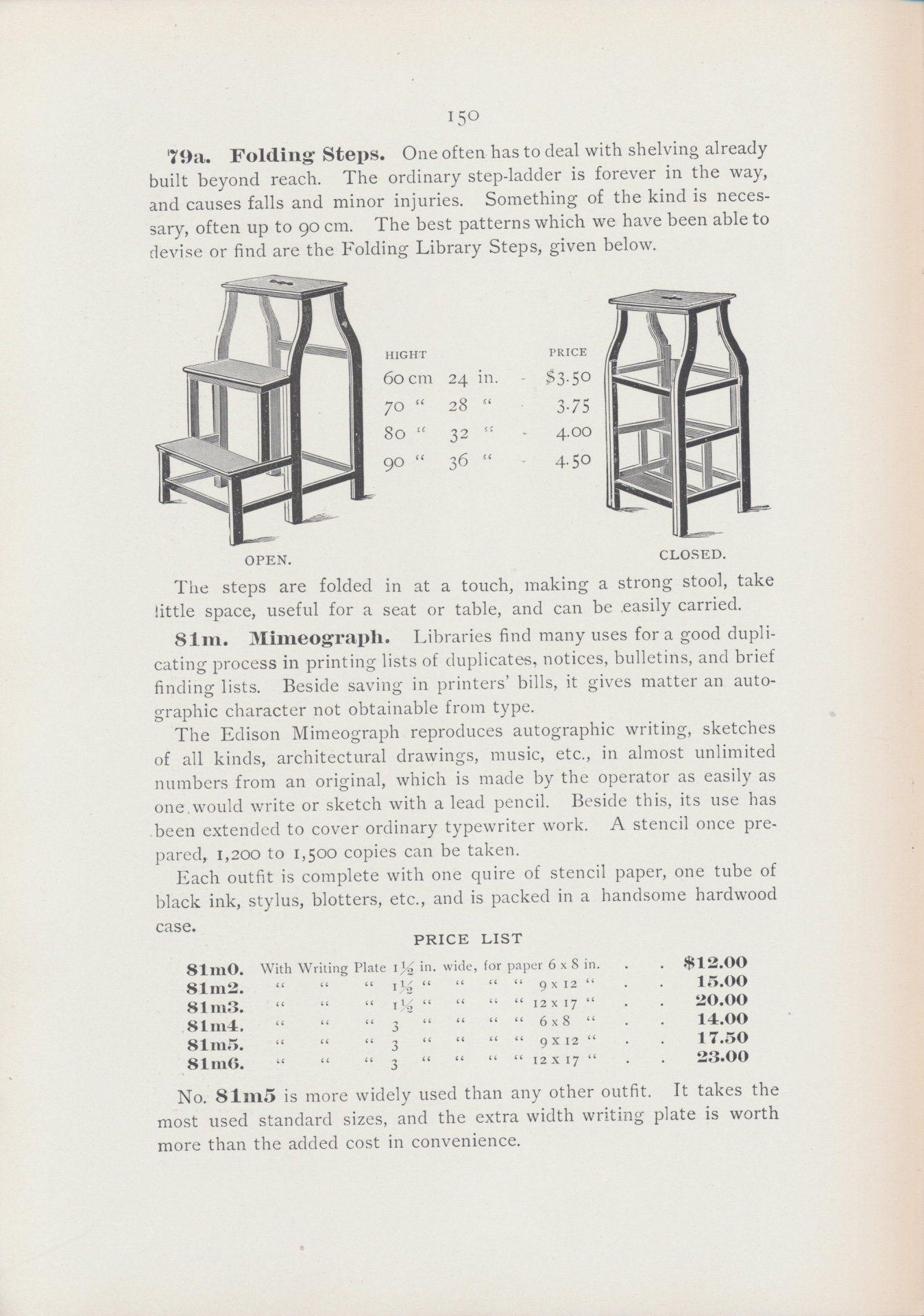

Every library needs step stools for reaching high shelves. These Folding Steps, illustrated below, provided an additional benefit. How many times have we been browsing the stacks and located a book but needed a quick, safe place to set it down to take a closer look at a page? The Folding Steps provided a way to do that. Along with the step stool portion which consisted of two steps, there was also a flat surface at the very top where a book might be set down if needed. These portable steps measured between two feet and three feet in height and were capable of being expanded outward to create the step stool portion or folded inward if only a stool or the flat/table top surface was needed. Both positions are shown below.

As we flip through this trade catalog, we are reminded of how much has changed in libraries over the last century, but it also shows that we continue to share some basic ideas and concepts with our predecessors. Classified Illustrated Catalog of the Library Department of Library Bureau (1899) and other catalogs by Library Bureau are located in the Trade Literature Collection at the National Museum of American History Library.

Be First to Comment