This is the fourth in a series of ongoing blog posts from Smithsonian Libraries and Archives’ Audiovisual Media Preservation Initiative (AVMPI), spotlighting the labor of Smithsonian media collections staff across the Institution. CK Ming currently serves as a Media Conservation and Digitization Specialist at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

Walter Forsberg: Hi CK! Always great to see you. Can you introduce yourself to our Unbound blog readers?

CK Ming: Hi Walter. Yes, I’m CK Ming. I’m a Media Conservation and Digitization Specialist at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. I’ve been working here for three years—it will be four, in July. I work with Blake McDowell, AJ Lawrence, and Ina Archer, who are my main team of folks. But I also work with staff from the Robert F. Smith Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History. Like my title says, I work on conservation and digitization of media collections. When I’m not onsite, I help create public programming for the Smith Center and the Earl W. and Amanda Stafford Center for African American Media Arts (CAAMA). I also work on collections justifications.

WF: Can you tell us about what ‘collections justifications’ are?

CKM: Justifications are a museum tool that we research and write in order to acquire collections. They include the history of provenance for the objects or collection, statements about their significance, and rationales for why the museum might want to acquire them and how they might use or exhibit them in the future. I work with various curators on that research, and then the justification goes to the museum’s Collections Committee. They vote on whether, or not, to acquire it.

WF: Can you share something about recent acquisitions you’ve helped bring into the museum?

CKM: One of the first things I worked on was an audiocassette interview with Rosa Parks that a 16-year old student made, after Parks moved to Detroit. In it, Parks talks about her work in the Civil Rights movement, but also about what she thought were the major issues affecting African Americans at the time. I think the interview was conducted in the 1980s, so that was really cool and surprising. We’ve also had several home movie collections come in, which are always fun to work on. Oh, and also the opening animated credits to the Black Journal television show. That title sequence was for the intro they began using in the 1972 season, and was made by an animator named Carmen D’Avino. I think they came from a film laboratory closure. When labs go defunct, they often dispose of a lot of original film elements that were used for making copies.

WF: Yes, I seem to recall that those came from DuArt Labs in New York City. Maybe I even served as the official donor of record?

CKM: That’s right. Honestly, the thing that helped us the most in identifying those were the digitized episodes of every season of Black Journal that the American Archive of Public Broadcasting ended up putting online. I just trawled every season’s intro to find out when they were from and who made them. We also recently accessioned a cinema verité film made about James Baldwin when he lived in Turkey called, James Baldwin: From Another Place, made by Sedat Pakay. It’s only eleven minutes long but Pakay has other photos in the museum collection of Baldwin from that time. The voiceover is of Baldwin talking about America, and his thoughts about being an expat.

WF: I don’t think our job timelines overlapped at NMAAHC, but you did spend a week scanning home movies with us for your previous position in Chicago. Can you talk about some of your career path that led to you joining the museum?

CKM: Prior to NMAAHC I spent four years working for the South Side Home Movie Project at the University of Chicago. Jacqueline Stewart is the director and founder of that project, which collects home movies from residents of Chicago’s South Side. Working there was really fun and a good introduction to home movies and how they shape culture and can affect history. The collections capture historical moments from all of South Side Chicago’s 74 community areas, dating from the 1920s to the 1980s. I was very involved in building up that archive, getting physical and digital storage, creating a catalog, and—my proudest achievement—actually putting collections online in a publicly searchable website. Justin Williams has now taken the reins and is doing really great things with the project. That experience of running an archive really led me to the museum: inspecting film, digitizing media collections, and working with donors. It was great preparation for working on the museum’s Great Migration Home Movie Project.

WF: Tell us more about that inititiatve.

CKM: It’s an award-winning public program that we’re hoping to re-start after having paused during the pandemic. Families visiting the museum can drop off their home movies in the morning, and pick them up at the end of the day when they also receive a USB drive with digitized files of the material. The program has been a great source of African American home movies and I think we have digitized for over 100 families. People can look for that coming soon.

WF: I know that you worked at MoMA after graduate school, but can you speak a little bit about when your passion for film developed, growing up in St. Louis?

CKM: My passion for the cinema really started in high school when I saw Moulin Rouge! (Baz Luhrmann, 2001). It was like nothing I’d ever seen before and it sparked an interest in how movies were made, who makes them, and the variety of different roles people play in production. My undergrad degree from American University was in film production with a minor in cinema studies, and I took a great silent film course. One of the things my professor said that stuck with me was the fact less than 10% of films produced in the ‘silent era’ survive. It led me to think about black filmmaking in that period, after discovering the work of Oscar Micheaux—one of the earliest black film directors, who made Within Our Gates (1920). If only 10% of that era’s film survive, then it must be closer to 2% of black films that survive. I applied to grad school and studied film preservation at NYU.

WF: It’s fascinating to look back on how nuanced experiences and personal encounters have helped to direct our lives’ paths, isn’t it?

CKM: Thinking back on it, now, my grandmother was a librarian and so is one of my aunts. Two of my great aunts were, as well, so I suppose I took over the family business.

WF: Our Unbound readership will appreciate those librarianship shout-outs! Can you talk about what it’s like working at the Smithsonian? I’m always curious about people’s impression of it before, and after, they work here.

CKM: Well, my Aunt Terrell is an early childhood educator and she actually worked at the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center. I remember visiting DC with my family and Aunt Terrell gave us a behind-the-scenes tour. I was nine or ten years old, and everything we saw was incredibly cool. It’s amazing to have ended up working here. I find this work so rewarding because of the large group of A-V archivists I get to interface with. In my previous jobs I was often the only person working with audiovisual collections, but here I can bounce ideas off my numerous colleagues in AVAIL [the Smithsonian’s audiovisual archivists working group], or pass by another unit’s laboratory to see how they approach similar problems that I might be facing.

WF: Can you share any specific challenges you’re working on at the moment? Do you have any ‘soapbox topics’ you feel like sharing?

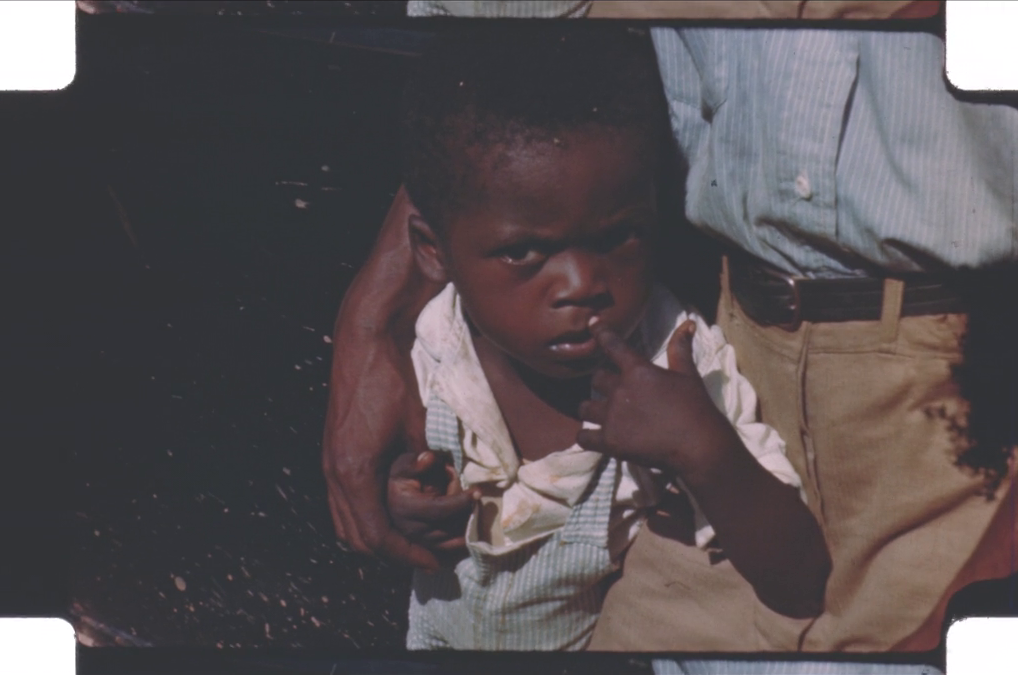

CKM: One recent soapbox I’ve been thinking a lot about came up last week when some graduate students toured the museum conservation lab. It surrounds the fact that none of the legacy media formats we work with were ever made to capture footage of people with darker skin tones. So, how do we—as archivists—reckon with that? And what are we doing in preservation and restoration projects to account for that? When color correcting scanned amateur film footage, sometimes we’ll adjust the slider and discover people in the frame who weren’t being picked up by the film’s exposure. I’m trying to figure out how to create a larger conversation about that in our A-V archiving community.

WF: That seems particularly relevant, too, given the current online Reddit craze of colorizing old black and white footage and photographs.

CKM: With moving images it’s often particularly bad because people so rarely link back to the original artifact or footage. I’ve seen so many Twitter posts where, say, a snowball fight from 1896 is colorized, but nowhere is it mentioned that the footage was originally black and white. As the archivists, how can we best frame the topic of authenticity in a world of AI, and get the original material out there so people have the context that color photography did not exist at that point?

WF: What are your upcoming projects?

CKM: I’m really excited about the upcoming year, restarting the Great Migration Home Movie Project and bringing the community archiving workshop model to organizations in need across the country.

Be First to Comment