This exhibition and blog post were curated and written by Joana Stillwell.

Sonic Strategies in the Library accompanies the newly opened exhibition Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Musical Thinking, by Curator of Time-Based Media, Saisha Grayson, focuses on video art that uses sonic strategies including scores, improvisation, and interpretation, as well as styles, structures, and lyrics that speak to American life. The works selected for this accompanying exhibition at the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library (AA/PG) include books from the collection as well as materials from the artist files. Nine selections ranging from the early nineteenth century to the 2010s reveal the ongoing and evolving relationship between visual art and music and sound.

Music: A Mere and Colorful Memory

Before the advent of recorded sound, music was a medium only available to a live audience, and only recollected orally, or venerated in the visual arts. Painting was considered the main art in the early twentieth century and its ability to capture the essence of music was the focus of Luna May Ennis’ Music in Art (1904). This is embodied by the beautiful red and gold cover which centers a ribboned and stylized painter’s palette, while the border is compiled of different types of stringed instruments, pan flutes, and white flowers. The book is organized among themes of myth and enchantment, youth and love, worship and are punctuated by illustrations by Donatello, Raphael, Rubens, and more. The book reads as art historical analysis but through the perspective of a viewer trying to relive “the sound [that has died] with the vibration of the strings [and] with the breath of the singer becom[ing] a mere memory.”

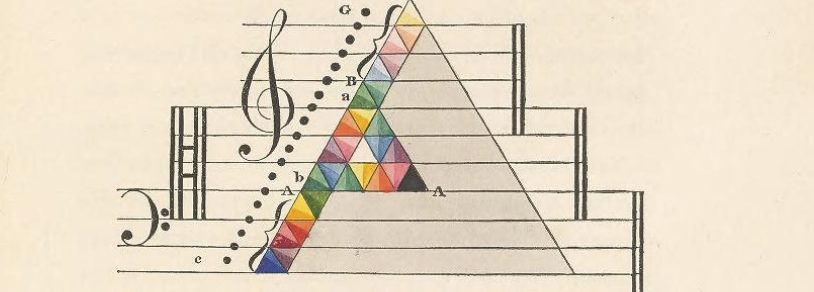

George Field’s Chromatics, or, an essay on the analogy and harmony of colours (1817) contains rich hand-colored wood-engravings with letterpress captions. Field was known as a chemist and for being especially skilled with pigments but fell short on being a color theorist after ignoring Isaac Newton’s ideas regarding color and light. Regardless, this book reveals his artistic sensibilities while expressing his theories on the relationship between the spectrum of colors and the scale of musical tones.

The Potentiality of Scores

By the twentieth century, music and sound recordings were readily available, which heightened the exceptionality and spectacle of the event or live performance. John Cage, a seminal influence on music, sound art, performance art, and more, was fascinated by the ability of music to make the listener more aware of their present. Cage argued any vibration of a particular moment could be considered music. While living in Europe as an art student he “noticed [on a street in Seville] the multiplicity of simultaneous visual and audible events all going together in one’s experience and producing enjoyment. It was the beginning of the theatre and circus.”

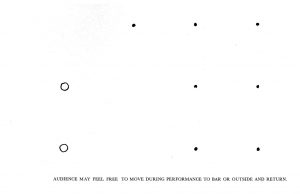

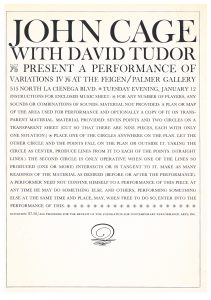

Variations IV (1965) is a work by Cage with composer David Tudor. It was presented at Cage’s first gallery concert, and is only remembered through printed instructions and a music sheet. The instructions read, “A performer need not confine himself to a performance of this piece. At any time he may do something else. And others, performing something else at the same time and place, may, when free to do so, enter into the performance of this.” Herbert Palmer, the owner of the gallery, recollected in a 2004 interview that Cage was in one room while Tudor was in another and between them were stacks of records and tapes.

He remembered that each would turn on different recordings and the music would change depending on where you were in the space. Palmer expressed, “It was so wild, with all the different kinds of music going at once.” More of Herbert Palmer’s interview is available at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Raven Chacon is an artist featured in Musical Thinking where a video work and original lithographs of four different scores are on display. The publication For Zitkála-Šá is a collection of this series of scores and the one selected in our exhibition is for his sister, Autumn Chacon. Similar to Cage’s musical sheet, there is a large location assumed or suggested. As a Diné and Xicana sound artist, activist, and community member, Autumn’s work examines contemporary methods of storytelling which dovetails into her work as a pirate radio engineer. In this score, Autumn is instructed to place, locate, and interact with lamps and radios while tracing her movements on the “score-map.” Every time the score is completed, a new path and story is forged and at the end she is invited to “sing the new song that [she] learned while performing the score.”

Soundscapes: Interpretations, Reverberations, and Process

In 2015, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery inaugurated its first performance art series, “Identify: Performance Art as Portraiture.” One of the performances, Identified by María Magdalena Campos Pons and Neil Leonard, was a study of President Abraham Lincoln, with the goal of reinserting the Black body into historical narratives evoking protest and devotion. The performance took place throughout the museum and its atrium. Portfolios containing 22 cards with texts, illustrations, and one musical score were handed to viewers. The score was performed by jazz musicians from Philadelphia, New Orleans, and Havana, a wind ensemble from the Duke Ellington School of the Arts, and folkloric musicians from Matanzas, Cuba. Together they reverberated the history that ties them together on the site of Lincoln’s second inaugural ball.

A promotional pamphlet for a monograph and two sound works, titled Finding Pictures in Search of Sounds (2008), depicts abstract fragments that question the interpretation of sound visually, aurally, and physically. The pamphlet by electronic musician and media artist, Stephen Vitiello, is a selection found in the AA/PG Library’s Art and Artist Files. The monograph contains individual booklets that act as visual clues to the sound pieces. Images of forests, reeds in water, and lines that mimic scores and wires can be vividly spread around a space without a distinct order and holds its own presence and experience. This pamphlet is just a shadow of the works it promotes, but reflects Vitiello’s practice of transforming unobserved atmospheric noises into engaging and imaginative soundscapes.

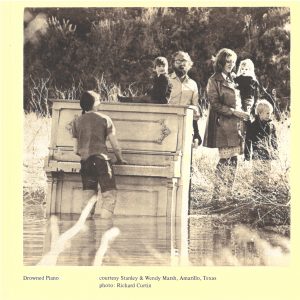

Womens Work (2019) is a facsimile of a publication from the mid-1970s. It was a magazine that highlighted the overlooked work of 25 female artists working with music, performance, and visual arts. Co-editor Annea Lockwood emphasized “We wanted to publish work which other people could pick up and do: that aspect of it was really important…this was not anecdotal, this was not archival material, it was live material. You look at a score, you do it.” One of the works in the book is by Lockwood herself and titled Piano Transplants (1968-1972). She cautioned that all pianos used for these performances should already be beyond repair, as she wrote and performed scores for the burning, drowning, and gardening of the instrument. She is particularly enamored with the environment, especially water, and collaborates and improvises with dancers, musicians, aquatic insects, and more.

George Brecht’s Water Yam (1963) was first published as a method to cheaply disseminate art democratically – widely and easily. Brecht was an important member of the experimental Fluxus art movement. The movement stressed the significance of the artistic process over the art product. The movement’s philosophy was grounded in experimental music and it was named after a magazine that featured artists and musicians who were influenced by John Cage. Water Yam is a box that contains many small, printed cards with instructions referred to as “event-scores.” Brecht became known for his haiku-like scores that left room for interpretation. Fourteen event-scores punctuate all three AA/PG Library display cases and were selected for their musical, performative, and tangential connections. These event-scores range from seemingly mundane tasks such as disassembling and assembling a flute, ambiguous encouragements of string quartets to shake hands, to supposedly more direct instructions to turn a radio on and then off at the first sound.

In the spirit of Musical Thinking, the library selections highlight visual works where music and sound – its memory, creation, and lived experience – is the primary focus. It also reveals how the visual arts has and continues to praise, document, and provide new pathways and interpretations of the fleeting medium. A particular event-score by Brecht feels like a fitting selection with which to conclude:

This exhibition and blog post were curated and written by Joana Stillwell, the Audiovisual Archivist at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive (MARMIA), who was the 2022 ARLIS/NA Wolfgang M. Freitag Internship Award recipient and was hosted at the Smithsonian American Art and Portrait Gallery Library. The exhibition will be on view from July-October, 2023, in the AA/PG Library.

One Comment

[…] Sonic Strategies in the Library (Smithsonian Libraries and Archives) […]