National Garden Month blasts off with zinnias, written by Robin Everly and Julia Blakely.

Smithsonian Libraries, most days, is like a typical library system — we assist staff and visitors with information needs, purchase books, check in journal issues, digitize, catalog, and of course, shelve books. However, the Smithsonian being the Smithsonian, sometimes your ordinary day turns upside down into something else. It’s what makes working here so fun and interesting.

Such a day occurred November 10, 2016, when a Smithsonian Gardens’ horticulturist contacted our librarian in the Botany and Horticulture Department about attractive 19th-century books featuring information about zinnias. He was working with a National Air and Space Museum (NASM) film crew on an educational program about Astronaut Scott Kelly’s growing zinnias on the International Space Station (ISS). The botanical librarian, along with our catalog librarian in the Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History, came up with some stunning botanical illustrations and set up a display in the rare book reading room for the filmmakers. From these collections, there was a fine selection to peruse. So this got the two librarians involved in this project wondering about zinnias, this old-fashioned flower, now getting its moment in the sun — well, in the cosmos.

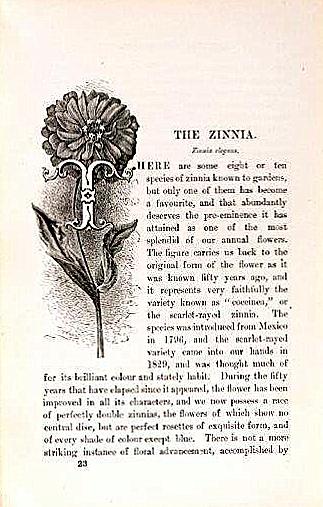

When Spanish Conquistadors came across the native perennial in Mexico they were so unimpressed that they called the zinnia “mal de ojos” or “sickness of the eye.” It was a meager, scrawny looking bloom and the 16th-century Europeans ignored it. It was not until the late 18th century that seeds were collected and brought to Europe for propagation. Appropriately enough, given its derisive earlier appellation, the zinnia was named for German physician and botanist, Johann Gottfried Zinn, who did research on a membrane of the eye, now known as the ciliary zonule or zonule of Zinn. He wrote the first complete anatomy of the eye, Descriptio Anatomica Oculi Iconibus Illustrata (1755). Zinn also was the director of the Botanical Garden of Göttingen University.

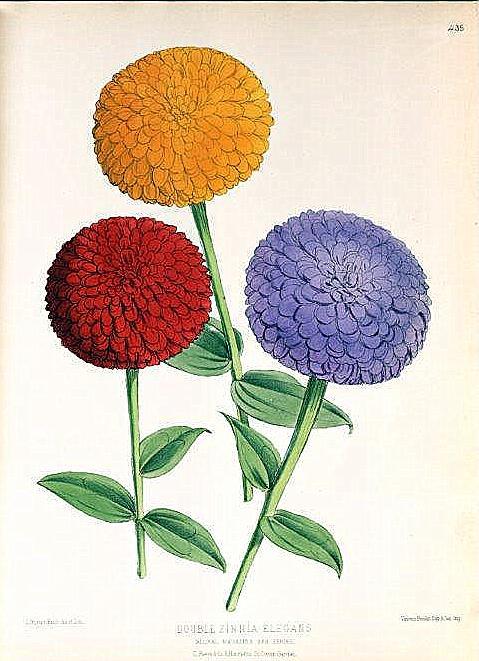

With the invention of plant hybridization and introduction of double flowered types, the best-known Zinnia elegans became fashionable in the 19th century and was employed as a bedding-out or border plant. This popularity relates to the development of lithography in graphic reproductions used in advertising. Chromolithography, with eye-catching, vibrant colors, was a great means for producing enticing portraits of zinnias for the horticultural industry. The second half of the 19th-century was, in general, a flourishing time for illustrated botanical works.

Zinnias are very easy to grow and are treated as an annual in northern climes, although they can self-seed from year to year. They are the humble flower of the garden and available in a wide palette of colors, all except for blue. In the mid-Atlantic, zinnias bring back life into gardens during the dog days of August. They are a great cutting flower with their sturdy stem and tendency not to drop petals. Best of all, zinnias are a good plant to attract butterflies and bees. Their bright colors attract these essential pollinators as well as hummingbirds. Particularly attractive to Monarch butterflies, zinnias provide food and an egg-laying habitat. Inexpensive and not prone to disease, zinnias are a flower for these climate-challenged times.

The horticulturist was filmed discussing the zinnia’s “flower meaning.” For centuries, there has been a “Language of Flowers,” that is, blooms’ symbolism or sentiment. For example, the iris means faith, promise or hope. Sometimes a specific color has different connotations for one flower: a red rose represents love, respect, or unity while the white rose is for purity or silence. The 19th-century books we referenced state that the zinnia’s general message is “thinking (or in memory) or an absent friend.” The magenta zinnia means lasting affections, the scarlet is of constancy, white of goodness and yellow is for daily remembrance. All very good thoughts for a long stay in space.

All this made the zinnia a great choice to be grown on the ISS. As anyone who has nurtured a plant on a windowsill knows, it is so pleasing and soul-satisfying about watching something grow from seed to bloom. There is something particularly wonderful about bringing color and life to the International Space Station. The long-term goal is to grow and provide fresh vegetables to astronauts on long missions such as to Mars or beyond. Other plants have been grown on spaces stations such as zucchini, sunflowers and soybeans. But it sounds from the astronauts’ communications back to us on this green earth that growing plants in space provided a needed spiritual nourishment as well.

Be First to Comment