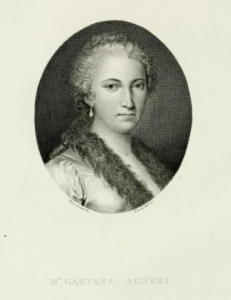

“George Sarton, a founder of the history of science as an academic discipline, argued that scholars should pay close attention to portraits. These images, he said, can give you ‘the whole man at once.’ With a ‘great portrait,’ Sarton believed, ‘you are given immediately some fundamental knowledge of him, which even the longest descriptions and discussions would fail to evoke.’ Sarton’s ideas led Bern Dibner to purchase portrait prints of men and women of science and technology. Many of these are now in the Smithsonian’s Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology.” – Deborah Jean Warner, Curator, Physical Sciences Collection

A picture may tell 1000 words, but another 500 for context can add depth to the image. Although this particular portrait is not held in the Dibner Library, this fascinating woman of science is well-worth exploring through her visual depiction. Follow this blog series to discover the people behind the portraits.

If life is a combat between the flesh and the spirit, as Maria Gaetana Agnesi believed, then this portrait perfectly illustrates her constant struggle. Her deliberate life-choices are reflected here, with hair simply styled and very few accessories. She was born in 1718 into a wealthy family in Milan to a father who bartered not only their wealth but Agnesi’s brilliance for entrance to the highest social strata. Unlike her father, Agnesi whole-heartedly rejected the trappings of wealth. Her humanitarian contributions are often overlooked, but were to her just as important if not more so than her mathematical investigations—all were done in the service of achieving a more perfect spiritual life.

A child prodigy, Agnesi was constantly asked to perform for Milan’s nobility by her father. When she was 11 she would dazzle the crowd by conducting discussions with attendees in seven languages, including Latin, Greek and Hebrew. As her education continued she would hold conversaziones or disputations on the current scientific and philosophical questions of the day, an atypical performance for 18th century Milan. One attendee, Charles de Brosses, conseiller at the parliament of Dijon, said she spoke like an angel. Agnesi, however, took no pleasure from these performances. Brosses quotes her as saying “For each person who was genuinely interested, there might be 20 who were bored to death.” It was Agnesi’s correspondents who were her most interested and dedicated audience.

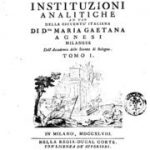

Agnesi’s education was conducted in large part by letters. She would read and work independently, and was encouraged to contact specialists when she required more explanation. This network, developed during her own youth, was maintained while she wrote Instituzioni analitiche ad uso della gioventù italiana (1748), or Analytical institutions for the use of Italian youth, an introduction to the extant works of Euler. She came to be respected as a mathematician in her own right, and was appointed by Pope Benedict XIV to the Bologna chair of mathematics, natural philosophy and physics—the second woman to be granted a professorship at a university, though she never served. Instead, after her father’s death, she devoted herself almost entirely to theology and ministering to Milan’s poor and elderly.

As the first woman to write a mathematics handbook, and with the curve the Witch of Agnesi named for her, it is unlikely Agnesi will be forgotten in the history of mathematics. But her approach towards learning also puts her at the forefront of the Catholic Enlightenment. She was driven by faith in everything she did, believing that the highest possible achievement of human intellect is the intellectual knowledge of God. Only then could she find perfect natural happiness.

Come to the Dibner Library to see a first edition of Agnesi’s handbook in English for yourself.

For further reading on Maria Gaetana Agnesi, check out Massimo Mazzoti’s The world of Maria Gaetana Agnesi, mathematician of God, 2012.

Be First to Comment