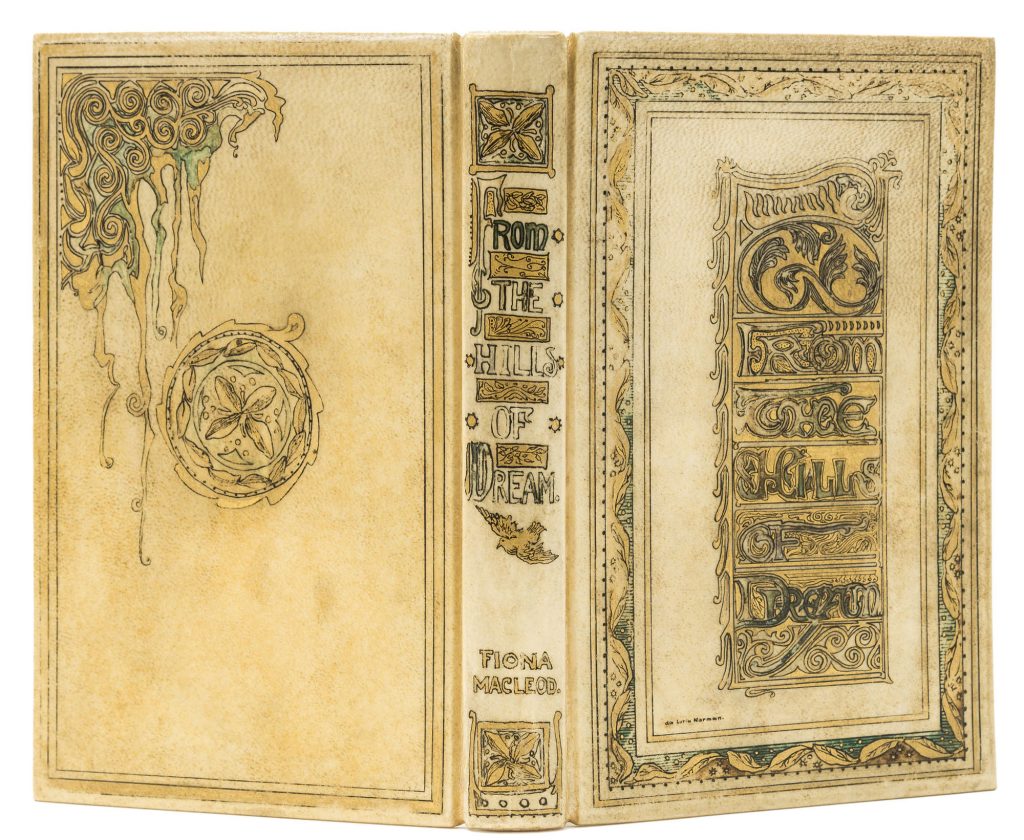

The Smithsonian American Art and Portrait Gallery Library has in its collection a book of poetry bound in a beautiful hand-painted vellum cover, with scrolling Celtic calligraphy and designs of delicate spirals and leaves in gold and green. From the Hills of Dream: Threnodies, Songs and Later Poems contains a collection of poetry, but this book also gives us a glimpse of the interesting relationship between an eclectic, progressive artist and an enigmatic poet with a secret.

From the Hills of Dream, an anthology of poems by Fiona Macleod, was published in 1907, just over a year after the poet’s death. The Scottish author burst onto the world stage in 1895 with a lengthy illustrated piece in the December issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, a particularly notable feat to have such a spread in a nationally known magazine for a previously unknown female poet.[1] Her work was a whimsical blend of prose and poetry with Celtic themes, and Macleod was among the most notable contributors to the Celtic Revival in the arts in the 1890s.

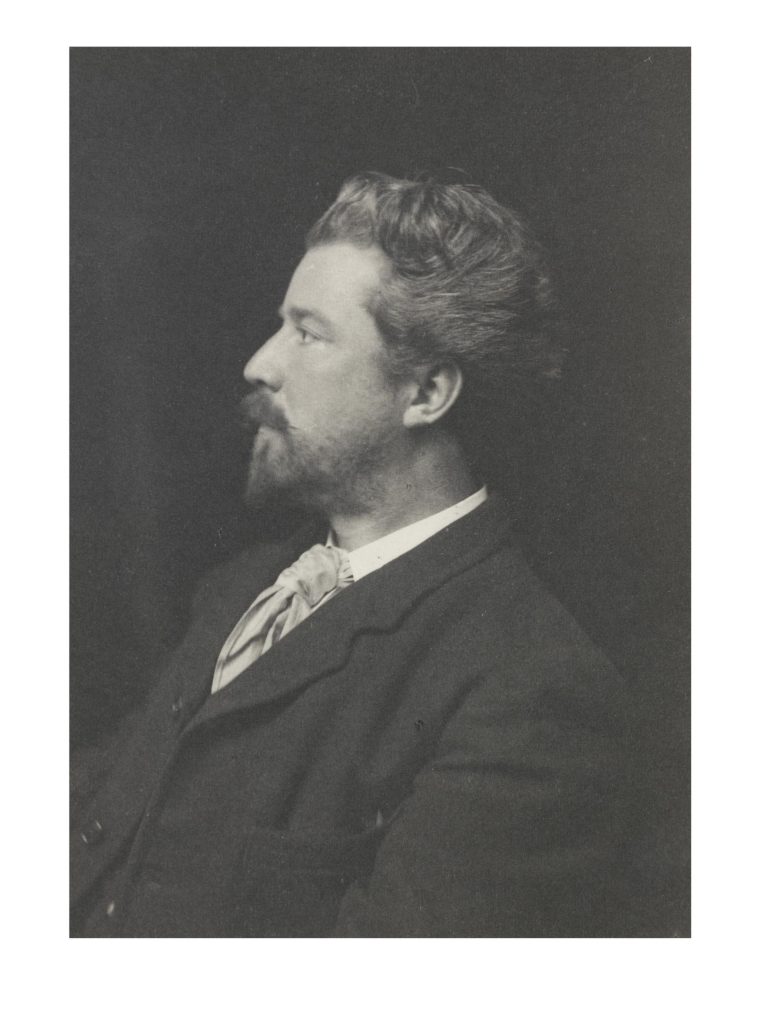

Macleod was particularly private and, after publication of her first book, refused interviews or engagements to speak. Her growing popularity during the Celtic Revival only made her more sought after, and the secrecy caused much speculation, particularly in the popular press. In 1905, the New York Times called Macleod’s identity “the most interesting literary mystery in the United Kingdom in the past ten years.”[2] In addition to her seclusion, Macleod’s publications were all mediated through fellow Scottish poet, editor and critic William Sharp (1855-1905). Sharp moved in the same circles as Dante Gabriel Rosetti and wrote well-regarded poetry and biography. During his lifetime, there were many rumors about the relationship between Macleod and Sharp, including that they were cousins or lovers.

One review of the early first edition of Macleod’s From the Hills of Dream called it “fierce, passionate, unearthly…the power of the book is wonderful and unquestionable. The brain behind it seems to have probed deep down and comprehended all possibilities of heart and pleasure.”[3] Perhaps it was this sensitive storytelling that first attracted the artist da Loria Norman, and inspired her to begin writing to Macleod in early 1905. Macleod wrote back, and the secretive author and the budding artist kept an active correspondence until Macleod’s sudden death later that year.

Da Loria Norman (1872-1935), was born Belle Mitchell in Kansas, she moved with her family to England during her childhood, and later married and had three boys. The marriage was not a happy one, and Belle left her husband for the first time in 1903.[4] In separating from her husband, Belle embraced a life of art, music and travel. She had started using the name “da Loria” at this time, which seemed to signal a break from her traditional life of a middle-class wife and mother in the Victorian age. Self-taught, da Loria became adept in watercolor painting and illuminations of books and images. These passions also allowed her to see beyond the confines of her marriage, as a way to support herself and her children.

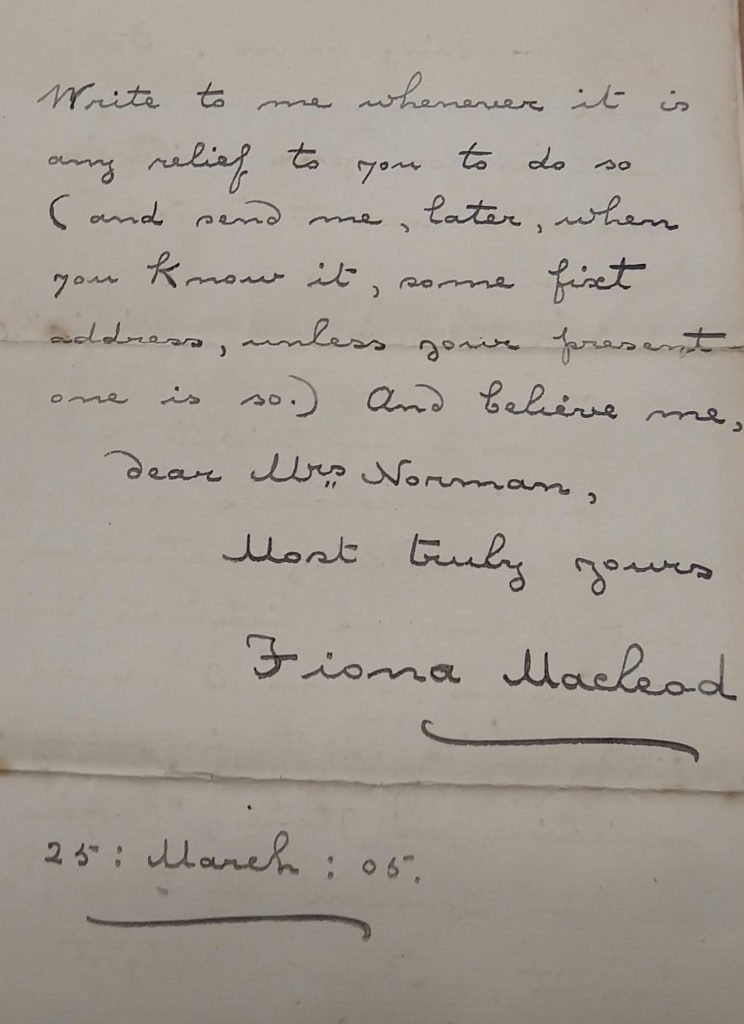

Da Loria’s first letter to Fiona Macleod in 1905 must have asked permission to bind and illuminate a work of the poet, and Macleod’s reply, in delicate curving handwriting, offered both her consent and interest in da Loria’s work as a “fellow artist.”[5] Their further correspondence, only known through Macleod’s responses, shows a burgeoning friendship, in which Macleod called da Loria “dear one” and said she has spoken to her heart.[6] Macleod sent da Loria books and offered recommendations for publishers. She gave advice to da Loria on her marital challenges, sympathizing that to “make one’s living by the thought of the mind and the craft of the hand, and to begin the battle without resources and with three young children to support, is a heroic task.”[7] It was in this period that da Loria’s marriage completely fell apart, and she took comfort in the poetry and letters from Macleod, asking her to visit at several points.[8] Macleod always had a kind word, but also an excuse as to why it was not possible for the two women to meet.

The reason for these excuses became plain to da Loria and the world when William Sharp died suddenly at the age of 50 in December 1905. His death-bed confession surprised the literary world with the revelation that he was the real Fiona Macleod. Sharp’s wife, Elizabeth, later described his deception as necessary to liberate the romantic part of his nature and poetry. Furthering the ruse, Sharp would send his correspondence first to his sister, who would copy them in her distinctly feminine handwriting, and send the copies on as “Fiona.” This tangled deception likely contributed to Sharp’s early death, as the work load it took to publish as two different authors and the incredible amount of correspondence that he felt compelled to keep up were not conducive to his already delicate health.[9]

We do not know how da Loria took the news of Macleod’s death, or the realization that during her most difficult period, she had unwittingly bared her soul to a man. In 1909, seemingly out of nowhere, Elizabeth Sharp wrote to da Loria, acknowledging that she was a valued friend of “Fiona Macleod.” What followed was a long friendship, in which the two women did meet several times, and wrote dozens of letters over many years, even after da Loria had moved back to the United States.

Just after the death of “Fiona Macleod,” da Loria sought a formal divorce, and the case became sensational, reported on in excruciating detail in the London and area press. To support her family, da Loria undertook commissions from wealthy patrons, illuminating their most treasured books and manuscripts, and partnering with such luminaries as Walter Crane. She became fairly well-known for this illumination, and a later critic noted her work was the “outcome of personal suffering, ardent faith and pure inspiration.”[10] With the onset of World War I, da Loria took the opportunity to leave Europe, and sailed to New York with her eldest son in 1914, where she had her first solo exhibition at the venerable Goupil, Cie & Co. later that year.

The Smithsonian’s copy of From the Hills of Dream was owned by the British composer John St. Anthony Johnson, and just recently donated to the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library by the descendants of da Loria Norman herself.[11] We do not know the details of the endeavor, though it was likely produced on commission, as the vellum cover, the gold leaf paint, and the cost of professional binding would have been too great for da Loria to take on without a purchaser in mind. But it was clearly a work undertaken with great care by the artist, as an homage to the powerful words the work contained, by a poet she didn’t truly know, but still considered a friend.

[1] Macleod had just published her first book in May 1894 (Pharais: a Romance of the Isles. Derby [England]: Harpur and Murray, 1894.) Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. V.92 Dec. 1895. Pp. 45-61

[2] “Sharp’s Death Solves a Literary Mystery: English Author and Fiona Macleod Were One and the Same.” New York Times. New York N.Y. 15 Dec 1905: 2.

[3] The Literary World; a Monthly Review of Current Literature. Boston. Vol. 28, Iss. 3, (Feb 6, 1897): 35.

[4] “Mrs Norman’s Worries.” The Courier and Argus. Dundee, Scotland, July 13, 1906; pg. 6

[5] Letter from Fiona Macleod to da Loria Norman dated 4 Feb 1905. Da Loria Norman Papers, 1886-1980. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[6] Da Loria Norman Papers, 1886-1980. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[7] Letter from Fiona Macleod to da Loria Norman dated 25 Mar 1905. Ibid.

[8] Norman v. Norman Civil Divorce Records, National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Class: J 77; Piece: 854.

[9] William Sharp (Fiona Macleod): A Memoir, Compiled by his Wife Elizabeth A. Sharp. New York: Duffield & Co, 1910.

[10] Crump, Elizabeth Enders. “Da Loria Norman—Illuminator.” International Studio. Vol. LXXIII, no. 289 (Apr 1921). Pp. lii-liii

[11] Smithsonian Libraries’ copy was a gift of Lucy Norman. In addition, the family donated da Loria’s work and papers to the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Archives of American Art, respectively, and the intriguing story of da Loria Norman was first researched and written by Cynthia Ann Norman in her unpublished, undated essay “Da Loria Norman: An American Illuminator Rediscovered.”

Be First to Comment