In a society that largely relies on motor vehicles for transportation, or even for sport, it may seem difficult to understand why it was so monumental for a plucky twenty-year-old woman to be allowed to participate in bicycle races, meets and other activities involving the sport. However, what transpired between the young woman and many cycling critics would prove to be a landmark in both the history of gender and racial issues.

Katherine Towle Knox, known as Kittie, was born on October 7, 1874 in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. She was the daughter of a white mother, Katherine Towle, and an African American tailor, John H. Knox. When Kittie was just around seven years old, her father passed away from an unknown cause. In the wake of her father’s death, Kittie, her mother, and her older brother Ernest moved to the West End of Boston on the corner of Irving and Cambridge streets. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, this particular area in Boston was home to an array of impoverished African Americans and immigrants. While the West End of Boston struggled financially, it seemed to be quite progressive in its successful integration of many different cultures in one neighborhood. Kittie found work as a seamstress and her brother found work as a steamfitter in an attempt to create a better life in an era that seemed to only create limitations for people of color.

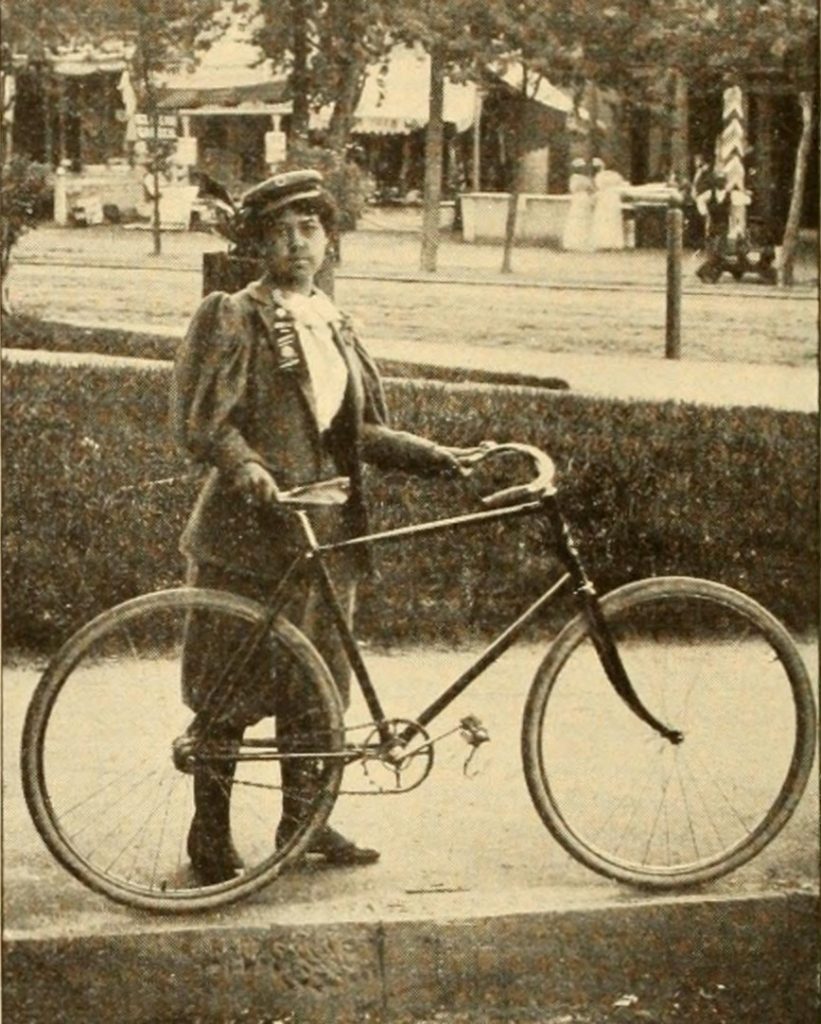

Kittie began to show interest in cycling early on in her life. After saving enough money from her job as a seamstress to buy a bicycle, Kittie became well-known in her neighborhood for her various outings. It was said that Kittie was a part of the Riverside Cycle Club, along with a few other friends and fellow female cycling enthusiasts. There is some speculation about whether or not they were actually considered card-carrying members, due to the general consensus at the time that women were not allowed to participate in a male-dominated sport. Kittie would continue to attract the attention of other cyclists as she began to participate in meets, winning many of the bicycling competitions she took part in.

In 1893, Kittie was accepted as a member of League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W). In 1894, the L.A.W. changed its constitution to include the word “white”, creating a “color bar” for the organization. This caused many members to question the legitimacy of Kittie’s membership. In his book Boston’s Cycling Craze, 1880-1900 , Lorenz J. Finison details some of Kittie’s experiences during this time.

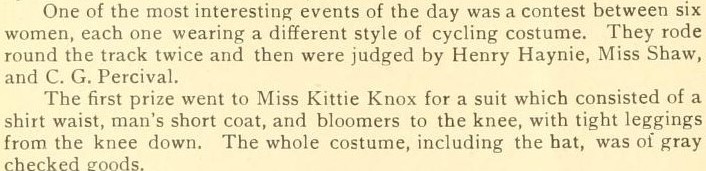

Despite her controversial membership, Kittie was a popular candidate in competitions that featured female L.A.W. members sporting their best looks. In the 1895 edition of The Bearings, a cycling journal, a section details Kittie’s first-prize win at an event in Waltham, Massachusetts:

Kittie became known for both her unique style and elegant riding technique but her appearance was frequently scrutinized by journalists. While the newspapers failed to describe in great detail how attractive any of the male cyclists were, they succeeded in giving an account of Kittie’s physical appearance and wardrobe in nearly every meet covered. She was at times described by journalists as a “comely colored maiden”, “murky goddess of Beanville”, and “beautiful and buxom black bloomerite”. Kittie seemed to inspire colorful phrases regarding her color and gender, despite the fact that these aspects had nothing to do with her ability as a serious cyclist.

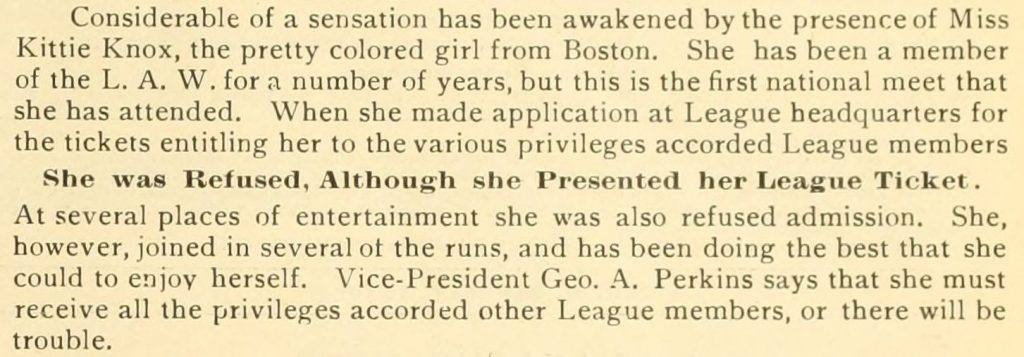

A particular incident in which Kittie showed her defiance occurred in July of 1895 when Kittie entered the annual meet at Asbury Park. It was reported that she was denied entry and was not recognized as a member of the L.A.W., despite being a card-carrying member. It was also reported that Kittie was denied service by restaurants and hotels while staying in New Jersey for the meet. This situation was promptly documented by The Referee and Cycle Trade Journal, as well as newspapers around the country:

Eventually, the issue of the “color bar” boiled over in the L.A.W. A battle ensued between the members who believed that the L.A.W.’s “white only” membership policy be upheld and those who felt segregation was wrong. In a July 1895 issue of L.A.W. Bulletin & Good Roads, L.A.W. stated that “Miss Katie [sic] Knox joined the League April 21, 1893. The word ‘white’ was put into the [L.A.W.] constitution, Feb. 20, 1894. Such laws are not and cannot be retroactive. We don’t know who it was that competed in the races and we know of no law that would keep a negro out of an open race, be he League member or not” (read a copy available through HathiTrust). After this statement was released, Kittie was accepted fully as a member, making her the first ever African American to be accepted by the League of American Wheelmen.

Kittie Knox’s story of courage in the face of racial tension helped desegregate the world of cycling and offered a hopeful vision for a future that accepts and supports diversity. Kittie is featured in several cycling journals held by the Smithsonian Libraries, such as the aforementioned The Referee and Cycle Trade Journal and The Bearings. Both journals can be found in the Smithsonian Libraries’ Digital Library. Much of her story is also detailed in the Boston’s Cycling Craze, 1880-1900, which can be found in the National Museum of African American History and Culture Library.

13 Comments

I have a mildly amusing ms. description of a lady cyclist on Congress St. in Boston on July 20, 1897, and would be glad to send you a copy if you have any interest.

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] made biking extra accessible to ladies looking for thrill, like early ladies’s biking champion Kitty Knox. In an period the place floor-length skirts have been the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to […]

[…] made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle […]

[…] Kittie Knox, Via […]