Originally published on the Smithsonian Collections blog …

Originally published on the Smithsonian Collections blog …

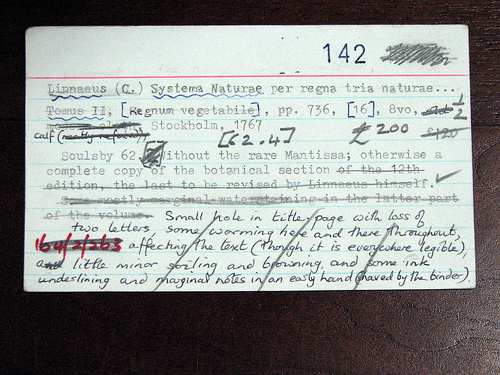

Top: one of the cards created and annotated by Wheldon & Wesley staff members.

Bottom: The cabinets containing Wheldon & Wesley's inventory cards, accumulated between the 1950s and 2000, now housed in the Cullman Library. The index has 90 file drawers. Because they were such prolific and important writers on natural history, there is one drawer devoted entirely to Darwin, and one drawer devoted to Linnaeus. The card file is the gift of Natural History Museum curators Drs. Storrs Olson, James Mead, and Roy McDiarmid, and Dr. Alan P. Peterson, M.D.

As part of our Archives Month 2010 celebration, archivists and librarians here at the Smithsonian are blogging about the work they do. I was asked to describe what it's like to be a cataloger. I filled up pages of notes with thoughts about the past, present, and future of cataloging archival and library materials, and, more specifically, about my job as Special Collections Cataloger for the Smithsonian Institution Libraries. It was a great exercise, but I generated way more information than I could pack into one entry. Therefore, I've suggested to my fellow SIRIS bloggers that we ought to do a continuing series on the glories and travails of cataloging (do you agree? Let us know in the comments section below!)

I think being a cataloger is one of the best jobs ever, but, generally speaking, cataloging has traditionally enjoyed a mixed reputation, even among other librarians and archivists. Catalogers are sometimes stereotyped as rules-obsessed and not particularly social, hidden away at the back of the office, in contrast to the friendly, outgoing image associated with reference staff. A good way to make someone's eyes glaze over at a party is to tell them that you write and edit the information that appears in online catalog records—but you should tell people this with a twinkle in your eye, because you know that as an archival or special collections cataloger, you get to work directly with the coolest of the cool materials. You're often among the first at your archives or library to have the privilege of looking through the new acquisitions, and you're also the one who examines the old treasures when it comes time to upgrade their catalog records.

Being a cataloger is a very important job, because your concise, expertly-informed, and accurately-crafted record makes it possible for your institution's reference staff, researchers, and others to find the materials they are interested in that are tucked away out of sight in the closed stacks. While cataloging manuals like Describing Archives: A Content Standard and MARC 21 Concise Formats are full of details that are challenging to understand and remember, the work is all worth it when you can create well-organized and easily findable records in SIRIS for unique materials. Featured here is the Wheldon & Wesley Card Index, recently acquired by the Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library of Natural History, containing the accumulated inventory and provenance notes of a British antiquarian book dealer who specialized in the sale of publications on natural history for over 150 years (and the Smithsonian was one of the company's best customers).

The job of cataloger has changed a lot over time in the data-driven environment of archives and libraries. Long ago, a cataloger made handwritten entries in a log book or on paper cards (somewhat like the annotated card from book dealer Wheldon & Wesley, shown above). Then typed or printed cards became standard. Now, our archival and library records are nearly all digital. Today at the Smithsonian, archival and library catalogers work closely with the information technology staff of their own units and the Office of the Chief Information Officer's SIRIS Team to come up with ways to improve the discovery and display of collections data from across the Institution.

This is an exciting time and an exciting place to be a cataloger, because there are so many ways that our records can be shared and enhanced. Increasingly, you'll find links to images or websites in our SIRIS records. We are looking into providing geographic data reference points with our catalog records. And in the coming year, we will be exploring ways to integrate mobile applications with the Smithsonian's Collections Search Center. We are also working on increasing the number of finding aids available in Encoded Archival Description (EAD) and other standard data formats to enable the Smithsonian to share and re-purpose its data with other research institutions around the world. What else lies ahead? Perhaps adding a crowd-sourcing component to allow catalog users everywhere to add their own keywords and notes to our records, while still preserving the integrity of the original data. These changes and improvements might seem like a tall order for now, but we will find a way to work things out, with so many bright minds working together here and in the greater archival and library community beyond the Smithsonian.

(The illustrations show one of the cards created and annotated by Wheldon & Wesley staff members; the cover of the printed sales catalog for Wheldon & Wesley's 160th anniversary; and the cabinets containing Wheldon & Wesley's inventory cards, accumulated between the 1950s and 2000, now housed in the Cullman Library).

—Diane Shaw, Special Collections Cataloger

2 Comments

I’m thoroughly enjoying reading this post. If you are ok with this, may I point to it from our CUA SLIS SLA Student group blog?

Thanks for the great insights!

Liz McLean

President, CUA SLA Student Group

Liz,

I would be thrilled to have this post linked on the CUA SLIS SLA Student Group blog! I hope there are some potential catalogers who will enjoy it. Thank you for responding (and my apologies for the delay in getting back to you!).