This post was contributed by Jessica Downie, 2018 Smithsonian American Art Museum summer intern with the American Art and Portrait Gallery (AA/PG) Library, and a rising senior at Bucknell University.

During my internship this summer, I have been working to merge a recent donation of materials from the Arts Students League of New York (ASL) with the AA/PG Library’s Art & Artist Files. Through the process I have come across a variety of different catalogs, announcements as well as letters and personal notes written to the director, secretary, and archivists of the ASL.

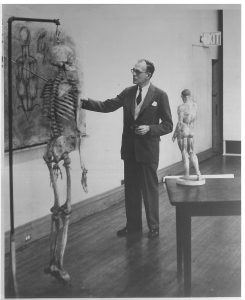

One artist’s file in particular struck my attention for multiple reasons, that of Robert Beverly Hale, a tall, slender man with round tortoise shell glasses who appears to have always worn a suit, from what we can tell in the many photographs found in the file. Hale was an abstract artist, first curator of Contemporary American Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a long-time art instructor at the Art Students League. Documents and ephemera saved in Hale’s many files over his 45 years at the ASL allowed me to get a glimpse into his classroom. Transcripts of his lectures on anatomy and life drawing indicate not only his talent for teaching art and creating art, but also his way with words and his excellence in speaking and writing. The way Hale speaks about art can be seen as art itself.

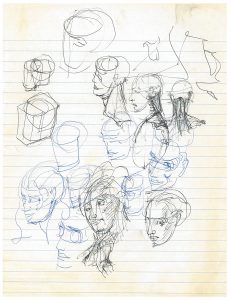

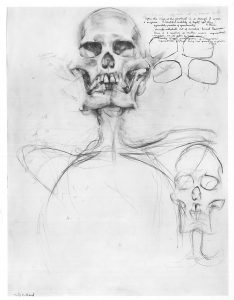

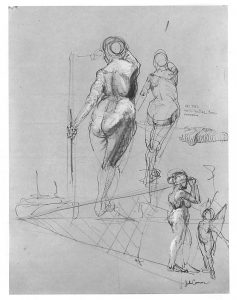

As I was flipping through the pages of Hale’s lecture “Elements of Drawing” I was struck by such simple phrases like, “where there is no light there is no form”[1], and intrigued by his ideas on drawing as a language and the artists expression of this language through “the illusion of simple forms… A wisp of smoke and his cylinder becomes a cigarette; placed beneath a head it becomes a neck…”[2]. Photographs of sketches from students in Hale’s classes bring to life what he speaks about in his lectures. There is something simplistically beautiful in sketches that expose the basic shapes underneath a larger drawing; it’s as if an artist becomes more human and more average when you see the method behind intricate drawings.

From looking at the contents of Robert Beverly Hale’s ASL file I learned that Hale was also very interested in science. In an interview from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art in 1968, Hale mentions that he was initially took many scientific courses when he first started studying at Columbia to “try and fill the gaps in his knowledge”[3]. Hale’s interest in science is reflected in his exceptional skill in anatomical drawings.

There was also a transcript of a speech discussing an interesting relationship between artists and scientists, given by Hale at the Art Students League Centennial Dinner in 1975, just a few years before he retired from teaching. Hale reminded his audience that scientists had the technology to cause an immense amount of destruction. In an anecdote about a group of students from a nearby technical school who took classes at the League, Hale recalled telling the students that “science had actually sprung from art, that it had developed in those great periods when artists had looked at nature very closely and carefully, and had tried to record exactly what they saw. That, what we explained, was what scientists have been doing ever since.” Hale continued that the artist, unlike the scientist, “has always felt that the things he couldn’t see were just as important as the things he could see.”[4] Hale ended his story stating that many of these technical students “discarded their deadpans” and began to explore art and abstract ideas as full-time students of the League.[5] The purpose of this anecdote was to illustrate to his audience that it is the artist’s job to reach out to the scientists, who hold all the power and capabilities of destruction, so perhaps then they could see things from the eyes of an artist. In many ways, his speech is still applicable today; everyone can take a minute to stop and think about what the world looks like through someone else’s mind.

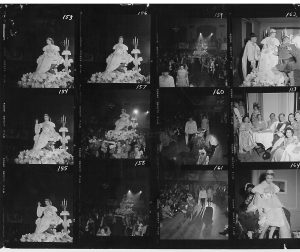

Exploring the contents of Hale’s file allowed me an opportunity for research, and like any good research project there are always more questions to be answered. There was something else that caught my attention among all of the papers, photographs and magazine clippings in Hale’s file, a contact sheet from a 120mm black and white film camera. I looked at the twelve imagines and recognized a beautiful young woman right away. It was the actress and singer Shirley Jones, young and beautiful, dressed in an elaborate gown. Shirley Jones is most famous for her roles in the musicals Oklahoma! and Carousel, and as a member of everyone’s favorite singing family on television, The Partridge Family. There is no date on the contact sheet and the only information stamped on the back says “USFeatures 146th W. 47th St., NYC” and “David Workman Photography”. From her appearance however, I am guessing that these pictures were taken around the late 1950s or 60s. Jones and several other people in the photographs are dressed in costumes with capes crowns and feathered hats. In several images Jones is shown seated on a throne on top of a flowered float carried by several men, and in another she is seated on a miniature horse. Despite my attempts at understanding what this event is and where and when it took place I am still left clueless. Why this contact sheet was placed in Robert Beverly Hale’s file from the Art Students League I guess I may never fully understand. Perhaps it was placed there by mistake or perhaps there is some strange connection to Hale hidden in the explanation of the photographs. Robert Beverly Hale’s file has been one of the most interesting to look at of the 1,300 files I have helped to process this summer, but I am sure the mysterious contact sheet with photographs of Shirley Jones will perplex me indefinitely.

–This post was contributed by Jessica Downie.

[1] Robert Beverly Hale. “Elements of Drawing.” Lecture at the Art Students League. 6.

[2] Hale. “Elements of Drawing.”4.

[3] Archives interview Oral history interview with Robert Beverly Hale, 1968 Oct. 4-Nov. 1. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[4] Robert Beverly Hale. “This Rising Dust.” Speech given at the Art Students League Centennial Dinner at the Waldorf Astoria, New York, NY. 17 October 1975.

[5] Hale. “This Rising Dust.” 1975.

4 Comments

Jessica,

Thank you so much for this thought provoking and insightful musing on RBH. I’m a devotee to his Video series especially, having watched it many times over now. Do you know of, or have access to any more images from this archive? OR any more information on his Elements of Drawing? I’m on the West coast and can’t view the archive in person. Email if so gwhipple@ucsc.edu.

Thanks,

Whipple

Hello

Noticed this Hale article.

I was Bob Hale’s assistant in the period around 1980, and am teaching a five lecture summary of Hale’s material in September on Zoom.

I worked with him in the period long after publishing of Drawing Lessons. He developed a unified theory of form discussed in his introduction to the Albinus book, that like all the other Hale books other than the first, was written by Terry Coyle.

If this material is of any interest to your readers, here is the link to the class.

I should have promoted it as a Hale class, but so it goes.

Best

Peter

https://ptschoolofthearts.org/classes/online-the-elements-of-renaissance-drawing-and-basic-anatomy-with-peter-goll-september-1-29

art.grantway.us

“Robert Beverly Hale, Lecture Notes,” by Sherry Camhy can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Reference and The Art Students League library. The book contains the photos of Hale lecturing, direct quotes, notes and sketches of his lecture drawings contained in my extensively, carefully detailed notations created during my years as Robert Beverly Hale’s ASL”monitor” assistant teacher. It is an unedited original reproduction of that sketchbook published in a collector’s limited large hardcover edition. There are a very few copies available.

http://www.sherrycamhy.com

Sherrycamhy@gmail.com

I studied at the Art Students League circa 1972 to 1974. Robert Beverly Hale was my primary instructor. He is one of the great influencers on my life and on the evolution of my intellect. Hale would say, “You see what you understand.” I learned how to see through a form and how to conceptualize space. The most important artistic thing that I learned from Hale was how to look at light. That “awakening” has been present in my daily life ever since. He also opened the door to the relationship between Art and Poetry. He would end his lectures with a poem. It was wonderful to sit with him alone in the gallery and talk about things like women and his relationship with Jackson Pollock. He made the life of an artist sound and feel important and valuable. Feeling valued and important was a lasting gift that he shared.