My favorite chronicler of natural and cultural histories in early America is Englishman John Josselyn. He was a curious and good-humored observer of the 17th-century inhabitants of northern New England, both indigenous and colonists, and their ways. Josselyn was particularly interested in local, medicinal uses of plants. Of what he referred to as “bill berries,” Europe’s closest relative to the blueberries, he reported that the fruit is used “To cool the heat of Feavers, and quench Thirst. They are very good to allay the burning heat of Feavers, and hot Agues [a fever that shakes the body], either in Syrup or Conserve.”

My favorite chronicler of natural and cultural histories in early America is Englishman John Josselyn. He was a curious and good-humored observer of the 17th-century inhabitants of northern New England, both indigenous and colonists, and their ways. Josselyn was particularly interested in local, medicinal uses of plants. Of what he referred to as “bill berries,” Europe’s closest relative to the blueberries, he reported that the fruit is used “To cool the heat of Feavers, and quench Thirst. They are very good to allay the burning heat of Feavers, and hot Agues [a fever that shakes the body], either in Syrup or Conserve.”

This native fruit is the low-bush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) that grows wild in the northeastern part of North America. Their stands spread on well-drained, highly acidic soil, only reaching about a foot in height. Blueberry barrens, rolling areas of sandy soil (usually treeless) along the foggy coastline, were first created naturally, then maintained by Native Americans. The berries produced from this rugged terrain are quite small and sweet and are far superior to the cultivated blueberry plants with fat, often mushy, fruit that populate markets today.

Josselyn was also attentive to local food and its preparation. He noted that the “sky-coloured” blueberries make for “A most excellent Summer Dish.” And further:

“They usually eat of them put into a Bason, with Milk, and sweetned a little more with Sugar and Spice, or for cold Stomachs, in Sack. The Indians dry them in the Sun, and sell them to the English by the Bushell, who make use of them instead of Currene [currants], putting of them into Puddens, both boyled and bakes, and into Water Gruel.”

A simple dish favored by Native Americans was called sautauthig, dried blueberries and dried, cracked corn mixed with water. Of the many foods proposed to have been served at the early thanksgiving feasts in New England, this pudding is one of the likely ones, according to historians. As related by Josselyn, the colonists added milk, butter and sugar, when available, to the mush.

Josselyn’s narratives are of his long stays and a catalog of what he saw and learned in the colonies in 1638 and, returning, in 1663. Details of what and how Native Americans and the early Europeans ate in North America are scarce and that makes New-Englands Rarities Discovered (1672) and Account of Two Voyages to New-England (1674) so valuable. Both volumes are in the Smithsonian Libraries’ Special Collections. The Biodiversity Heritage Library has digitized the original texts (links here and here) as well as later reprints. Josselyn throughout his two compendiums confirms that Native Americans were an important supplier of food to the colonists. In addition, the indigenous knowledge of climate, soil and growing practices was, of course, critical to the Europeans’ survival.

The English author resided mostly in Maine during his two extended stays. Blueberries still grow wild there, and further into Canada. Samuel de Champlain, in 1615 during one of his many explorations, gives the earliest known account of Native Americans (Algonquins) eating blueberries. The berries were wonderfully abundant, and the indigenous population dried them for winter use.

The Jesuit missionary Paul Le Jeune recorded in Relation de ce qui s’est passé en la Nouvelle France sur le Grand Fleuve de S. Laurens (Relation of what occurred in New France on the Great River St. Lawrence, in the year one thousand six hundred thirty-four) what the “savages” consume. “They eat, besides some small ground fruits, such as raspberries, blueberries, strawberries, nuts which have very little meat, hazelnuts, wild apples sweeter than those of France, but much smaller.” In another chapter, focusing on beliefs and customs, Le Jeune noted that “Some of them imagine a Paradise abounding in blueberries.”

Another account of a later exploration, Samuel Hearne’s A Journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Norther Ocean (1795; BHL link) observed that blueberries are “seldom ripe till September, at which time the leaves turn to a beautiful red; and the fruit, though small, have as fine a bloom as any plum, and are much esteemed for the pleasantness of their flavour.”

Dried blueberries were often an ingredient of pemmican, the original power food bar. Incorporated with pulverized dried fish or meat and melted tallow, and formed into cakes baked by the sun, this provision provided energy, lasted for months, and was easily portable on long journeys. Today, pemmican (a Cree word for rendered fat) is seeing a resurgence with the popularity of paleo diets and survival provisioning. Native Americans also gathered blueberries (or cranberries and huckleberries) and boiled for a few hours before simply being shaped into cakes and dried in the sun. In addition, the roots of the blueberry plant were boiled for tea by Native Americans.

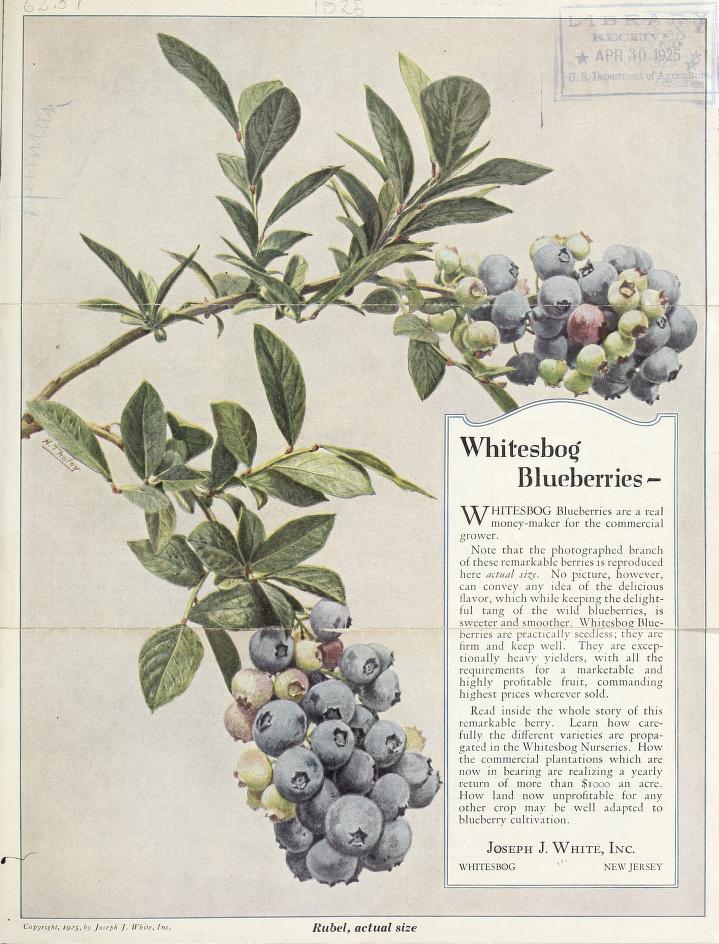

Food in the New World was, of course, essential for survival but also needed for commercial reasons, as products to sell locally as well as for trade to a ready audience in Europe and beyond. But commercial harvesting of blueberries was a late comer to the market and did not really begin until the 1840s. Then, as markets in the South dried up for exported seafood during the Civil War, canneries switched to wild blueberries, harvested from the barrens (link). And it wasn’t until the early 20th century that blueberries became a truly viable crop and commodity. That was when a government scientist, Frederick Coville of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, working with Elizabeth C. White of New Jersey of Whitesbog, New Jersey, began developing varieties of blueberries that could be grown on farms and in home gardens.

Much earlier, indigenous peoples used controlled burns to increase yields of blueberries, a technique still employed today. Every few years fields may be burned to eliminate old shrubs and fertilize the soil. Native American tribes, including the Micmac and Passamaquoddy tribes, working with government and private agencies, still maintain blueberry barrens, preserving this significant element of the rocky, coastal landscape.

Now, blueberries are touted with a wide-range of health benefits, from protection against heart disease and cancer, to maintaining bone strength, blood pressure and good skin, to controlling diabetes. They have become a trendy fruit in a variety of products. Full of antioxidants, they contain flavonoids believed to improve memory and slow age-related decline in mental function. Wild blueberries are said to contain twice the antioxidants of regular, commercial ones, with more phytochemicals such as anthocyanin.

However, the native wild blueberry business with recent high yields are in trouble, as the berries are commercially harvested mainly in Maine and are not as well-known. Passamaquoddy Wild Blueberry Co. of Maine, responsible for tribal blueberry operations, has recently cut back in production from their fields and barrens (story here). The wild variety is nearly impossible to transport fresh and, for export, are sold canned or frozen.

This Thanksgiving, in recognition of Native American Heritage Month, consider adding a wild blueberry pie, scones and muffins with dried berries or the original sautauthig pudding to your repast, honoring blueberries’ rich culinary and medicinal history in the Americas. And this native fruit, so intense in flavor, does make a superior pie.

For more information:

The University of Maine. Cooperative Extension. Maine Wild Blueberries (link)

“Blueberries to Potatoes: Farming in Maine,” Maine Memory Network (link)

3 Comments

A nice, informative account of blueberries in the early days of European exploration and the popularity of blueberries today. Agreed, the small wild berries have a more intense flavor than the oversize cultivated ones.

July being National Blueberry Month (thank you, USDA, for informing us of this, back in 2013) I will be writing an entry each week for my popular BelleWood Gardens web site. I want to request permission to use the image of the Whitesbog Blueberries catalog. Credit as “courtesy of the USDA, National Agriculture Library” O.K.?

Thank you for your attention to this request.

sincerely yours,

Judy Glattstein

the gardener at BelleWood Gardens

http://www.bellewood-gardens.com

I picked 800 pounds of blueberries in one season (only on extended weekends – a day added to the weekend). A record was 4 ice cream pails in an hour. That was 2013 – there will never be a year like that again.

I think I tried to out pick my Grandmother who picked 1 ton of blueberries and sold them for a loss to support her family. Now I am not sure if that was one ton or one tonne. Would like to believe it was a tonne.