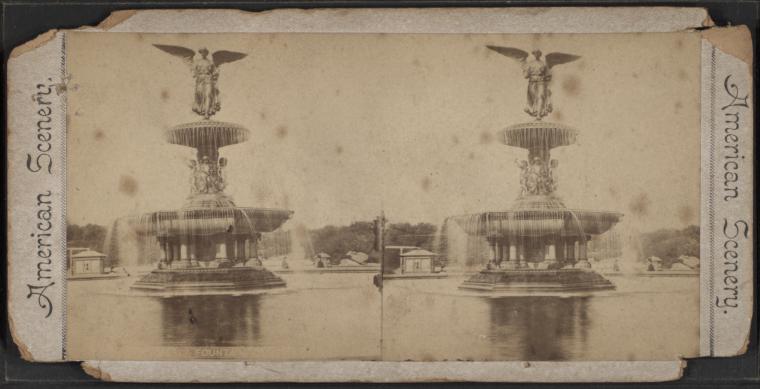

Few who walk past the Bethesda Fountain in New York City’s Central Park know the history behind the angel statue, standing high atop the fountain with wings outstretched. This sculpture, called Angel of the Waters, has been the backdrop for many movies and TV shows. The sculpture was made by a wealthy New York sculptor named Emma Stebbins, an artist featured in an album of cartes-de-visites (small, collectible photo cards) of notable 19th century American artists, located in the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library collection. Little is known about Stebbins, even though Angel of the Waters, as noted recently in the New York Times, was “the first public art commission ever awarded to a woman in New York City.”[i] However, what is known about Stebbins has been gleaned from the letters and press coverage of her relationship with famous American actress Charlotte Cushman.

Emma Stebbins was born into a life of affluence as the daughter of the wealthy banker, John L. Stebbins. The wealth and clout of her family allowed her to devote her life to a career of art, which was not often the case for women of lesser means. At the age of 42, Emma Stebbins travelled to Rome in 1857 and met with fellow American sculptor Harriet Hosmer who had arrived in Rome five years earlier.[ii] In Rome, Hosmer was part of a social circle of other independent (and often wealthy) women artists and creators, most of which lived in an apartment in Rome established by American actress, Charlotte Cushman. Cushman was particularly supportive of Hosmer and her work, using her celebrity to advocate for the sculptor. Stebbins was welcomed into this community of women and almost immediately began a romantic relationship with Cushman that would last for the rest of their lifetimes. In an 1858 letter to Emma Crow, Cushman alludes to marrying Stebbins noting “Do you not know that I [Cushman] am already married and wear the badge upon the third finger of my left hand?”[iii]

As the couple split their time between the United States and Europe, Cushman served as Stebbins’s greatest advocate and worked hard to promote her partner’s art. In one instance, Cushman rallied for Stebbins to win an 1859 commission to create a sculpture of Horace Mann that would be placed in front of the State House in Boston. Stebbins ultimately won, much to the dismay of Hosmer who no longer received the same support from Cushman.[iv] The most famous commission that Stebbins would receive would be for the aforementioned statue Angel of the Waters that would sit at the center of the Bethesda Terrace in New York’s Central Park.”[v] As reviews of the statue began to appear in the newspaper, Cushman was very vocal in both her admiration of Angel of the Waters as well as her disdain for those who were critical of it. As Cushman was retired (though she was happy to make special performances) it was noted by Cushman biographer, Lisa Merrill, that the actress spent more time on Stebbins’s career than her own at the end of her life. [vi] Ironically, after Cushman died in 1876 Stebbins spent much of the rest of her life on creating a biography of Cushman’s career, published in 1879, and ultimately stopped creating art until her death in 1882.

This focus on Cushman at the end of Stebbins’s life, as well as what seemed to be a general disinterest in self-promotion, helps explain the lack of information on Stebbins from her own voice. What is known comes mainly from letters written by Cushman to others and from newspapers of the time. Many American newspapers discussed them interchangeably whether they reported on Cushman’s acting tours or Stebbins’s sculptural works. Many examples of this can be found in the artist file for Stebbins located in the American Art and Portrait Gallery Library’s Colonel Merl M. Moore, Jr. Files, a collection of artists files focused on 19th century American artists that consist mainly of photocopies of 19th century American newspapers and magazines. For instance, Stebbins’s file included a clipping from the November 17th Boston Daily Evening Transcript from 1869 that reported an anecdote about how the couple took care of each other when they were ill: “I am sorry to say, however, that Miss Stebbins has been quite ill. She was with Miss Cushman during all of her cruel suffering, and of course, after the worst was over, Miss Stebbins’s nervous system was completely prostrated.”

The discussions of the relationship between Stebbins and Cushman in newspapers seem to celebrate the closeness and camaraderie of the couple without referring to it as a true romantic relationship which at the time would, of course, be considered taboo. However, Harriet Hosmer biographer, Kate Culkin, noted that, at this time, there was a certain “cultural acceptance of intense female relationships.”[vii] In part this “acceptance” came from the increasing occurrence of privileged women choosing to live with other women often for the sake of their career and independence. This allowed many lesbians to live together as couples under the guise that they had intimate, but platonic, relationships.

Another source of information about Stebbins is a scrapbook compiled by one of her relatives (now in the collection of the Archive of American Art) of images and newspaper clippings about the artist’s career. In the scrapbook, amid the photos of statues and hand written notes, there is a clipping of Stebbins’s obituary from the New York Tribune. While much of the clipping celebrates Stebbins’s artistic accomplishments, the entire last paragraph is devoted to the ways that her relationship with Cushman defined much of her life:

Miss Stebbins’s name is indissolubly linked with that of her friend Charlotte Cushman, with when she formed a close intimacy soon after taking up her residence in Rome. They lived together, travelled together and worked together for many years. It was one of those romantic and abiding attachments which indicate a genius for friendship. Miss Stebbins watched over her friend in her late illness and became her loving and appreciative biographer. Since the death of the great actress her own health has been declining.[viii]

[i] Jennifer Harlan, “Overlooked No More: Emma Stebbins, Who Sculpted an Angel of New York,” The New York Times, May 29, 2019.

[ii] History Project, Improper Bostonians: Lesbian and Gay History from the Puritans to Playland (Boston: Beacon Press,1998), 58.

[iii] Lisa Merrill, When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000), 211.

[iv] Kate Culkin, Harriet Hosmer: A Cultural Biography (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010), 96.

[v] Merrill, When Romeo Was a Woman, 201.

[vi] Merrill, 202.

[vii] Culkin, Harriet Hosmer, 63.

[viii] F, “The Late Miss Emma Stebbins.” New York Tribune, November 2, 1882.

One Comment

[…] life to a career of art, which was not often the case for women of lesser means,” stated the Smithsonian’s Unbound blog in […]