Wild Flowers of North America: Botanical Illustrations by Mary Vaux Walcott features more than 250 exquisite reproductions of Walcott’s celebrated watercolors of wildflower life. Edited by Pamela Henson, this stunning volume is a collaboration between Prestel Publishing and the Smithsonian Institution. We invite you to hear personally from Pam in this interview.

L: How did you become interested in history and first start out in your career?

P: I love science and started out as a biology major, but I earned my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in American studies from The George Washington University in the early 1970s. The George Washington University had a cooperative program with the Smithsonian, a precursor to its museum studies program today. During my master’s program, a group of us were hired by the Smithsonian to do a visitor behavior study at the National Museum of Natural History. I was hired as an “intermittent” (no fixed hours), not even part-time, temporary, GS-3 psychology aide. I learned a lot about how the public interacts with our exhibits, what works, what does not work. I then heard about an entry-level position with a new Smithsonian oral history project created by Secretary S. Dillon Ripley. I had done oral history interviews as part of my master’s thesis and was hired as the assistant, advancing all the way up to a GS-5! The project moved to Smithsonian Institution Archives and the historian was leaving, so shortly after that, I advanced to the historian position, and received a Ph.D. in history and philosophy of science from the University of Maryland. I’ve been in this position ever since, and I’ve loved it!

Describe your current role at the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

I am the Institutional Historian for the Smithsonian, in the Institutional History Division, Strategic Programs and Initiatives, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. I have several major functions. I provide background information on the history of the Institution to Smithsonian management, as well as scholars, the general public, and students. I also record oral history interviews with Smithsonian staff.

Smithsonian people often stay here a long time. The first interviewee was Charles G. Abbot who worked at the Smithsonian from 1895 to 1973 – 78 years! We record the lives of a wide array of our community, pivotal people like the security force, conservators, and educators. We are just about to launch a Smithsonian-wide project with interviews online, to gather the memories and reflections of the whole Smithsonian community at our 175th anniversary.

I also write, lecture, prepare exhibits, and do social media for both scholarly and popular audiences. I enjoy the variety of tasks I do, from interviewing an aeronautics curator, to preparing an exhibition on women at the Smithsonian, to helping set up a program on the history of information systems at the Institution. I’ve been at the Smithsonian since 1973, and I still get asked questions I don’t know the answer to.

Tell me about Wild Flowers of North America. How did you first get involved with this project?

My first office was in the Arts and Industries Building and it had two framed prints of wild flowers on the wall. I saw similar ones in the Smithsonian Castle when I moved to Smithsonian Institution Archives which was located there. I asked around and found out they were by Mary Vaux Walcott, wife of Smithsonian Secretary Charles Doolittle Walcott.

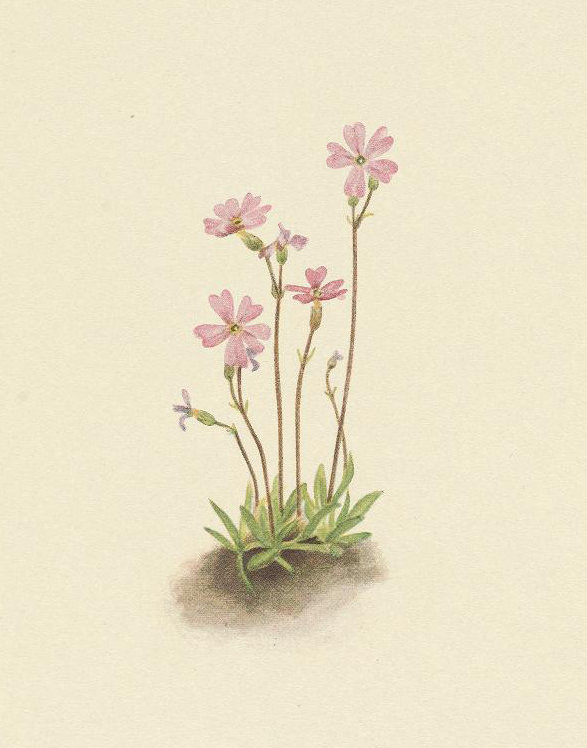

With my background in history of science and interest in the history of women in science, I’ve studied several Smithsonian women botanists, including Agnes Chase, a grass expert. I also studied the history of scientific illustration. Chase began as an illustrator. I’ve done exhibits and written on illustration that included both Chase and Walcott, but their styles were very different. Walcott’s were so beautiful – were they botanical art or scientific illustration? So I studied Walcott more. While her drawings were much more beautiful than Chase’s, they were very accurate, only contained the wild flower, not the surrounding environment. Her goal was to create drawings that introduced these flowers, many unknown, to the scientific world. So I concluded she was more a scientific illustrator than a botanical artist.

Why is the story of Mary Vaux Walcott important, and what about her life or work stands out to you the most? Did you uncover anything surprising in your research for the book?

Walcott is an example of how access to education for women was still limited, even after women’s colleges were established. Her work also shows how the field of botany was much more welcoming to 19th century women than other areas of natural history. It exemplifies the ways women were able to enter science “from the peripheries” such as art, as shown by scholars Margaret Rossiter and Sally G. Kohlstedt. She did not need to work, but had this incredible devotion to the task of creating visual images of and sharing all of these inaccessible wild flowers from remote sites in the Canadian Rockies.

I knew she married late in life, but I had not realized how strongly both families opposed the marriage.

I was very impressed with how fearless and resilient she was throughout her life. When she no longer had family to scale the high peaks of Canada with her, she went on her own or with other Quaker women. And she was not afraid to completely change her life at 55 by marrying Walcott and moving to Washington.

What are your favorite illustrations from the book?

I have a fondness for the first two I found in my office, a magnolia and a balsamroot. I like the curious ones, like the skunk cabbage; the really delicate ones like the Alberta primrose; as well as the ones that have such exuberance in their short lives, such as the saltmarsh gentian. And the diversity, the variety of ways plants have evolved to survive in almost any environment.

What do you hope readers take away from Wild Flowers?

A greater appreciation of these plucky plants that exist briefly in very difficult environments and a concern that we don’t lose them to climate change. And an appreciation of a plucky women who found a way to make contributions to science even when she faced many obstacles.

Any final thoughts/observations?

It is always a fascinating journey to get to know another person’s life – how Walcott constructed it, the doors that were closed to her, the paths she followed. Her story provides many life lessons.

One Comment

Great Job! I have the original book and grew up looking at it. I now am a botanical artist illustrating native orchids. I got inspiration from her book!