The Smithsonian will soon develop procedures for complying with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy’s directive on public access to federally funded research. That means that most papers authored by Smithsonian staff and affiliates will be made available to the public at no charge, some after an embargo period. There are several methods being developed by other federal agencies to meet this requirement and the Smithsonian has kept abreast of these policies. But aside from the White House mandate, it is clear that Smithsonian authors are increasingly making their scholarship freely available via publishing with an open access (OA) publisher. On average, there are about 350* OA papers published each year by Smithsonian scientists. This represents nearly 15% of research output.

Author: Alvin Hutchinson

Manages the Smithsonian Research Online program, a service which collects published research output authored or created by Institution scholars.

Organizations which respond to the changing needs of their clients are the ones that survive well. Here are two examples:

Shortly after General Motors began manufacturing cars in the early 1900s it created a unit (GMAC), which loaned money to car buyers and earned interest on these loans. Although known worldwide as an industrial powerhouse, eventually GM began earning far more profit from this money-lending operation than they did from auto sales. GM eventually sold the finance unit to pay off other debts.

A second example involves a much smaller company. Readers in the Mid-Atlantic region may remember Erol’s TV which started out in the 1970s repairing televisions and other electronics and later began renting video cassette players for home use. It wasn’t long before Erol’s began stocking VHS, Betamax and DVDs and became known primarily as a video rental store. They later sold the business to Blockbuster for $30 million. However the company continued to evolve in response to consumer demands, becoming an Internet service provider in the 1990s, competing with early ISPs like CompuServ, Prodigy and AOL.

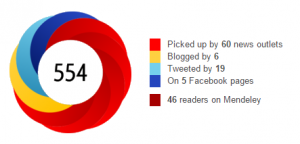

The digital age of publishing scholarly journals allows a wider variety of methods to evaluate usage and readership than that of traditional print articles. Online activity can be captured for each article almost immediately after publication, including number of times an article is viewed and downloaded or mentioned in online news outlets, twitter, blogs and other social media sites. (For more on altmetrics, see the earlier Unbound post.)

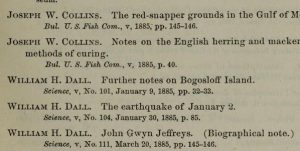

Thanks to support from the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Research Online (SRO) is adding a large body of legacy publications to its database this year. The source of the data is the annual reports of the United States National Museum (USNM) from the 1870s to the 1960s which often included an appendix listing staff publications. Some years there was no data listed, for example during World War II.

Thanks to support from the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Research Online (SRO) is adding a large body of legacy publications to its database this year. The source of the data is the annual reports of the United States National Museum (USNM) from the 1870s to the 1960s which often included an appendix listing staff publications. Some years there was no data listed, for example during World War II.

At a recent Open Access Futures presentation, speaker Rick Anderson noted that the music industry has moved from selling CDs to selling individual songs and he wondered whether academic journals might do the same. In other words, what if libraries one day stopped subscribing to scholarly journals but instead bought individual articles one at a time, in response to immediate needs by researchers?

As noted elsewhere in this blog, the publication record of Smithsonian scholars includes a growing portion of open access (OA) articles. During 2012, nearly 14% of scientific papers authored by Smithsonian scientists were published in OA journals. This is up from 7% in 2008 and it is expected to grow.

A frequently overlooked service that librarians provide to their users is that of selection for collection development. From the universe of available books, this service determines which should be acquired for a particular collection. Reference and subject-specialist librarians pore over an increasing volume of new book announcements and publisher and dealer catalogs, picking out the best titles that are appropriate for purchase and addition to the collection they manage.

But like many things we librarians do, the Internet has changed the game.