Last fall, I marked the season for the harvesting of grapes to honor John Adlum, the little-known “Father of American Viticulture.” The origins of the first commercially viable vine in the American wine industry can be traced to the District of Columbia.

Now, with the great interest in Alan Turing, the recent auction sale of this English mathematician’s 56-page notebook for more than a million dollars, and the success of the movie, “The Imitation Game,” let’s look at another (and earlier) computer pioneer genius, Herman Hollerith, and the importance of his Washington invention. Hollerith was, as stated in the title of his principle biography, “The forgotten giant of information processing.” Again, it was the beginning of a huge industry—surprisingly but not at all incidentally—in the nation’s capital.

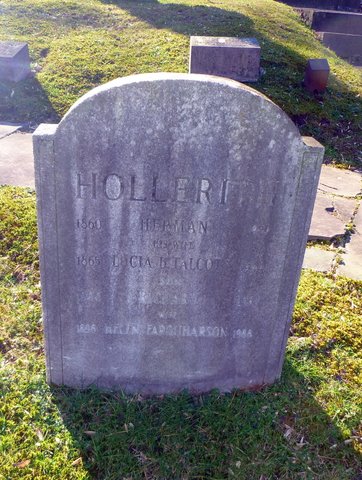

As it happens, the two stories of the early history of wine-making in the District and the modern data-processing era are linked, as there is a slight connection between Adlum and Hollerith (1860-1929).

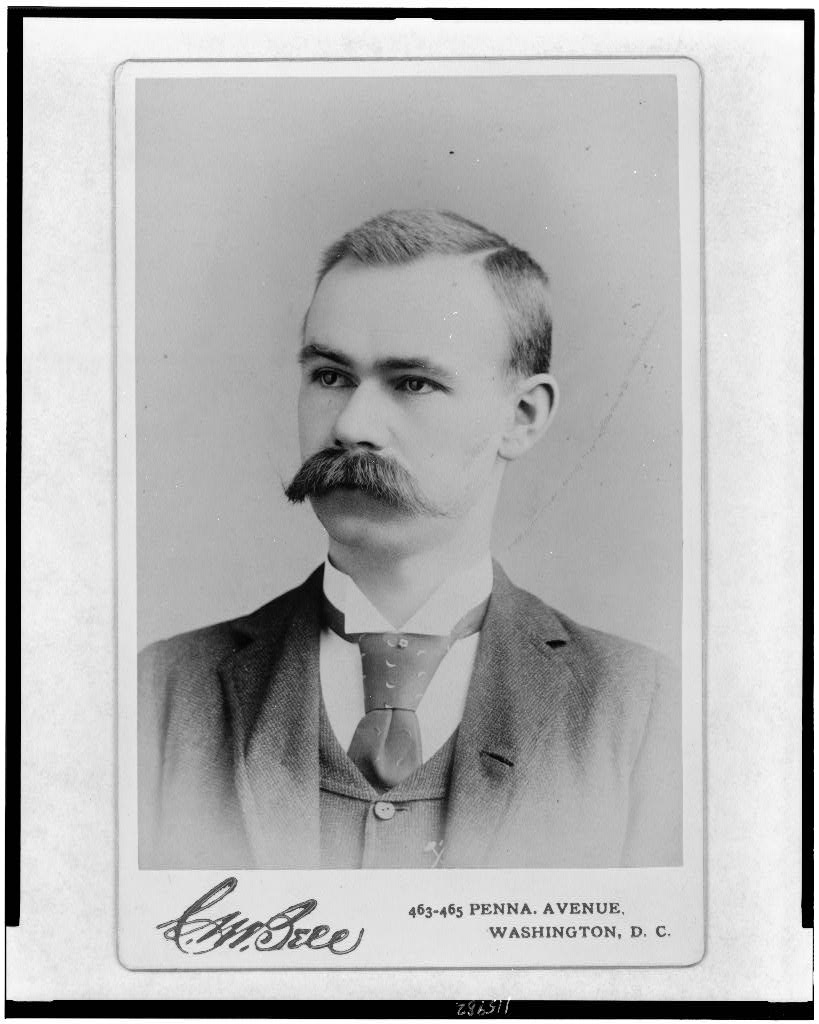

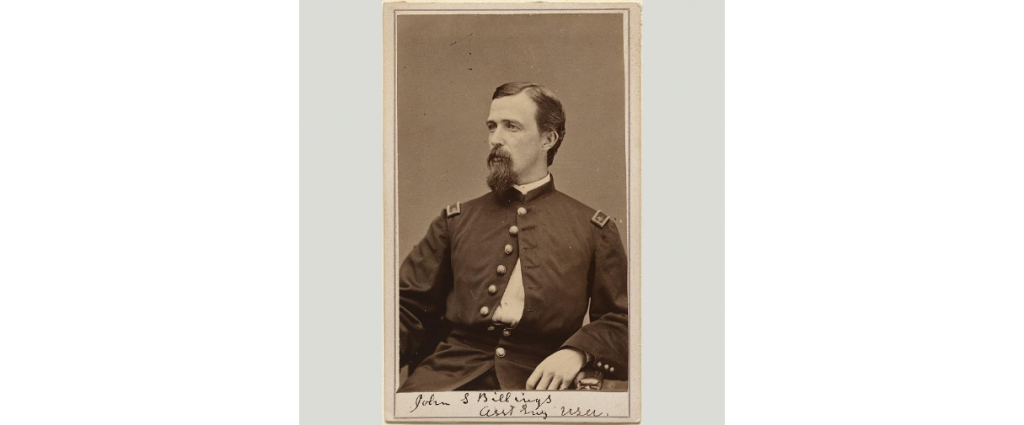

Born in Buffalo, New York, and educated at Columbia University, Hollerith began his career in Washington at the age of nineteen with work on the 1880 Census. After a brief academic appointment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a railway engineering stint in St. Louis, he returned to government employment in 1883, as a statistical engineer in the Patent Office in Washington. Initially through Kate Sherman Billings, Hollerith came to know her father, surgeon and librarian John Shaw Billings, then head of the Bureau of Vital Statistics at the Census. As acknowledged by Hollerith, Billings was an important influence on his career, helping inspire him in his later invention of the tabulating, punched card system.

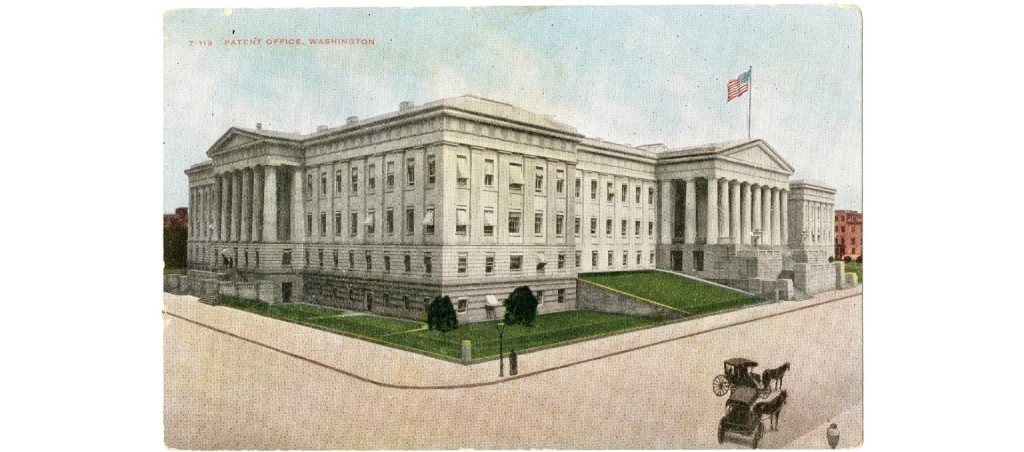

Also in government work was Hollerith’s future mother-in-law, Theodosia L. Barnard Talcott Hambleton (1840-1925). Along with Hollerith (for a short time), she worked at the Patent Office Building, now home to two Smithsonian museums, the National Portrait Gallery and American Art Museum, as a clerk from 1869 to 1899. Theodosia Talcott was one of the very first career female federal employees. After her husband Charles Talcott’s death in 1867, Theodosia continued to live at the family’s Washington estate with her mother and sisters, commuting downtown by the horse cart from P Street. According to Hollerith biographer Geoffrey D. Austrian, Theodosia’s professional position kept her family, including her son-in-law and his business, financially solvent at various times.

The home, “Normanstone,” was located where the British Embassy, sections of the United States Naval Observatory and Rock Creek Park, are now. Adlum’s “The Vineyard” was not far to the north and his daughter lived right next door at the splendid estate of “Northview” where the Observatory complex spreads. Theodosia’s mother had been a governess to the two Adlum daughters and her father was an executor of the wine maker’s estate.

Hollerith started his own business, “Expert and Solicitor of Patents” with Theodosia’s son, Edmund Talcott, as his first employee, in an office on 7th Street, near the Census building. He built on an earlier idea for the use of punched cards in combination with a machine. Billings had previously encouraged him to study Jacquard looms. The punched card system was actually invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1805 for the French textile industry and was later adapted by Charles Babbage for his calculator.

Hollerith’s sorter machines, with a pantograph punch and a “reader” of spring-loaded pins in electrical circuits, classified and counted the data for the 1890 U.S. Census in three months (different sources give varying times). By comparison, it took almost ten years to compile the hand-written information from the 1880 census which of course provided outdated results in the rapidly expanding country.

Other countries would seek his services and patented system. The Hollerith Electric Tabulating System grew (later named the Computer-Tabulating-Recording Company) and eventually became the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM).

Hollerith was married at “Normanstone” in northwest Washington on 15 September 1890, returned to live there as a newlywed, and, during a period of financial hardship in 1895 to 1896, moved back with his wife and (then) three children. After a time living in the nearby suburb of Garrett Park, Maryland, Hollerith built a grand new home for his family of six children in nearby Georgetown, on 29th Street, which was completed in 1911.

Hollerith died there in 1929. Thomas J. Watson, who had merged various businesses in 1924 to form IBM, attended the funeral. Hollerith is buried in nearby Oak Hill Cemetery, on the hillside below the Renwick Chapel, near the Adlum family graves. IBM in 1984 placed a commemorative plaque on his old Georgetown factory on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and 31st Street that was once his assembly and card manufacturing plant. In his earlier days, Hollerith organized barge parties on the Canal and was a member of the nearby Potomac Boat Club.

Hollerith’s old mentor Dr. Billings was a medical inspector for the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War. Later, with the Surgeon-General’s Office, he helped build their library collection from 600 to 50,000 volumes. Some of the former holdings have made their way into the Smithsonian’s Dibner Library. Billings also helped produce the Surgeon General’s Index Catalog, the great bibliography to all of medical literature. Much later, Billings came to organize the branch system of the New York Public Library and to actually sketch out an architectural plan for the main building.

Determining firsts is always a tricky business as is the compilation of a pioneering bibliography. It seems to be time for someone to write a carefully considered one on the history of computing, to include such figures as Jacquard and Hollerith. There is so much important information in the 20th century, papers in journals and manuals; essentially ephemera—works easily tossed aside and lost as newer and more advanced technology appears, such as IBM’s General information manual: an introduction to engineering analysis for computers of 1961. But where to begin? With Galileo? John Napier? Samuel Morland?

The Dibner Library would be a good start for research, with its holdings of such works dating from the 16th century. There are also manuscripts and publications of Charles Babbage (1791-1871). And one could wrestle with whether to include such titles as George Scheutz, Specimens of tables, calculated, stereomoulded and printed by machinery (London, 1857); William Farr, The English life table, no. 3 and the Swedish calculating machine (London, 1862?); Walter Hart, Book of instruction for the proportior or calculating disk (New York, c1889). It would be a task—what to leave in, what to leave out—and subject to debate and criticism. And where would one stop? At the beginning of the Internet Age?

In the meantime, let’s remember Herman Hollerith and his innovative work in and with the Federal Government to create computing machines. The vestiges of his life are still traceable in the landscape of Washington, if easily overlooked.

NOTES

Ashurst, F. Gareth. Pioneers of computing. London: Frederick Muller, 1983.

Austrian, Geoffrey D. Herman Hollerith: forgotten giant of information processing. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Bruno, Leonard C. Science & technology firsts. Detroit: Gale Research, 1997.

Essinger, James. Jacquard’s web: how a hand-loom led to the birth of the information age. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007 (QA76.I7 E88 2007 NMAH).

From Gutenberg to the Internet: a sourcebook on the history of information technology. Edited, with an introductory essay and an annotated timeline by Jeremy M. Norman (2005)

The Haskell F. Norman library of science and medicine. San Francisco: J. Norman, 1991.

Herman Hollerith’s tabulating machine. Blog post, Smithsonian Magazine, 2011.

Hollerith, Herman, “An electric tabulating system,” reprinted in Origins of digital computers: selected papers, edited by Brian, Randell. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1989, p. 133-144.

The Hollerith Family Slide Collection is the Smithsonian Gardens’ Archives.

Hook, Diana H. Origins of cyberspace: a library on the history of computing, networking, and telecommunications. Novato, California: historyofscience.com, 2002. With contributions by Michael R. Williams and Jeremy M. Norman.

Trueswell, Leon E. The development of punch card tabulation in the Bureau of the Census, 1890-1940: with outlines of actual tabulation programs. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1965.

2 Comments

[…] Care of the Peabody Room, here is a great article by the Smithsonian about Hollerith and his company. […]

Thank you. I love seeing Hollerith in color!