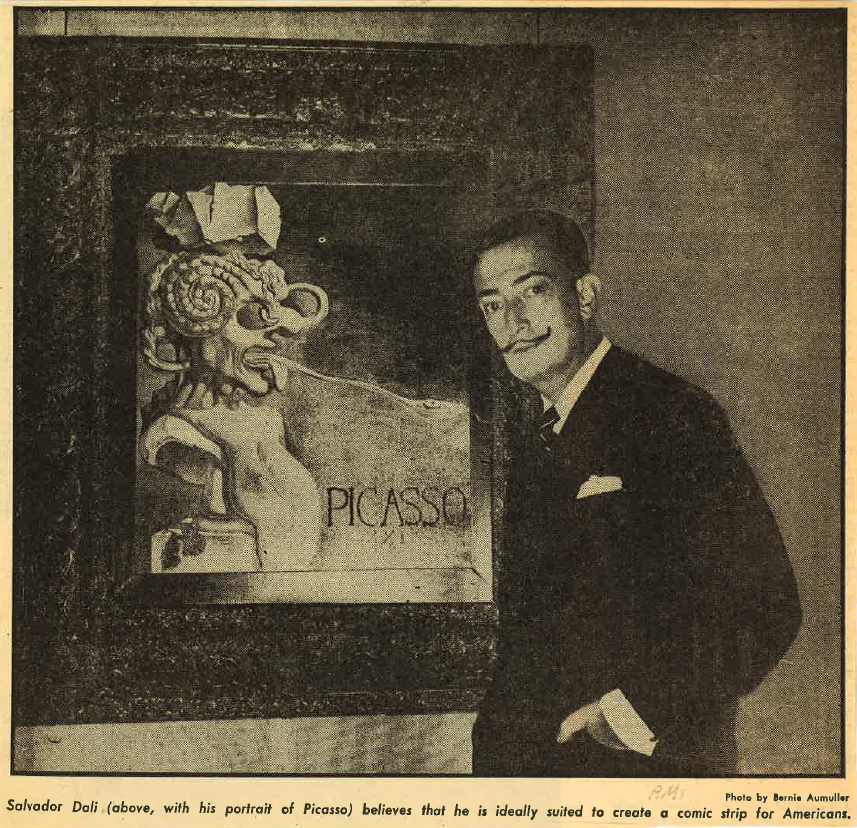

The brilliant sparkle of a diamond, the saturated blood-red of a ruby, and the rich deep blue of a sapphire become the building blocks of one of Salvador Dalí’s lesser known artistic enterprises: jewelry design. The renowned Catalonian artist, most famous for his mind-bending Surrealist paintings of dream worlds and for his eccentricity as a self-proclaimed “genius,” began to design his jewelry collection in 1941 and continued the artistic project until 1970.

Author: Sofia Silva

This post was written by Sofia Silva, Katzenberger Intern at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library and American Art & Portrait Gallery Library as part of a series exploring the Art & Artists Files at the Smithsonian Libraries.

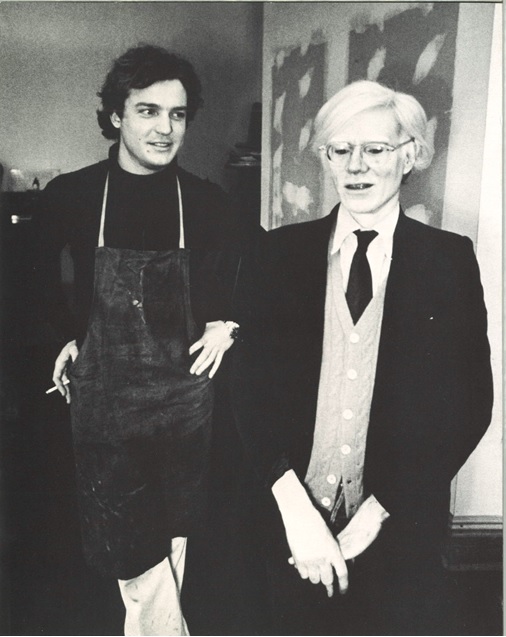

Though contemporaries, the artists James Browning Wyeth and Andy Warhol could not be more diametrically opposed. James, more commonly known as Jamie, is a third-generation member of the famed Wyeth family, who are celebrated as central figures in the revival of realism in American art (his father is Andrew Wyeth, painter of the American classic Christina’s World and his grandfather, N.C. Wyeth is acclaimed painter of vast landscapes and epic narratives of early Americana). Jamie continued this family tradition as a portraitist and landscape painter, whose naturalistic approach to painting produced highly detailed and visually complex work that captured life in rural Maine, Delaware and Pennsylvania.

If you think of Jean Dubuffet, Yves Tanguy, Balthus, Alberto Giacometti, Marc Chagall, and Joan Miró, you may instantly think of some of the most famous canvases and sculptures of modern art. These artists have been immortalized in art history as key figures within Modernism, a position made even more apparent by their countless works housed in some of the most important museums around the world. A name less recognizable is that of Pierre Matisse, the art dealer and gallerist who represented each of the artists mentioned above at various moments throughout his 50-plus year career.

If life were like a work of art, what would it look like? How would you take the most ordinary daily routine, such as breakfast, and transform it into an artistic masterpiece? While looking through the Art and Artist Files at the Hirshhorn Museum and American Art/Portrait Gallery libraries, I was given a better idea of what it would be like to have breakfast in the boldly graphic world of Roy Lichtenstein, one of the most important figures in Pop Art.

The world of modern art is at times criticized for a certain reputation of exclusivity and mystery in which the more inaccessible a certain artist or artwork may be, the more valuable and reputable the art becomes. Salvador Dali, the most famed member of the twentieth century avant-garde movement, Surrealism, on the other hand, challenges this perception that artistic creation is a closed-off affair for an elite few. Sure, Dali was no humble man of the people, and in fact is famous for his eccentric, narcissistic personality as he continually declared himself the most talented and significant artist of his generation (let’s not forget his autobiography graciously titled Diary of a Genius). However, Dali walks the line between artist and popular culture sensation as he created artwork that was meant to be seen and consumed by everyone. Many examples of Dali’s remarkable work may be found in the Art and Artists Files of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library and the American Art & Portrait Gallery Library at the Smithsonian, as well as the nearby National Gallery of Art Library.

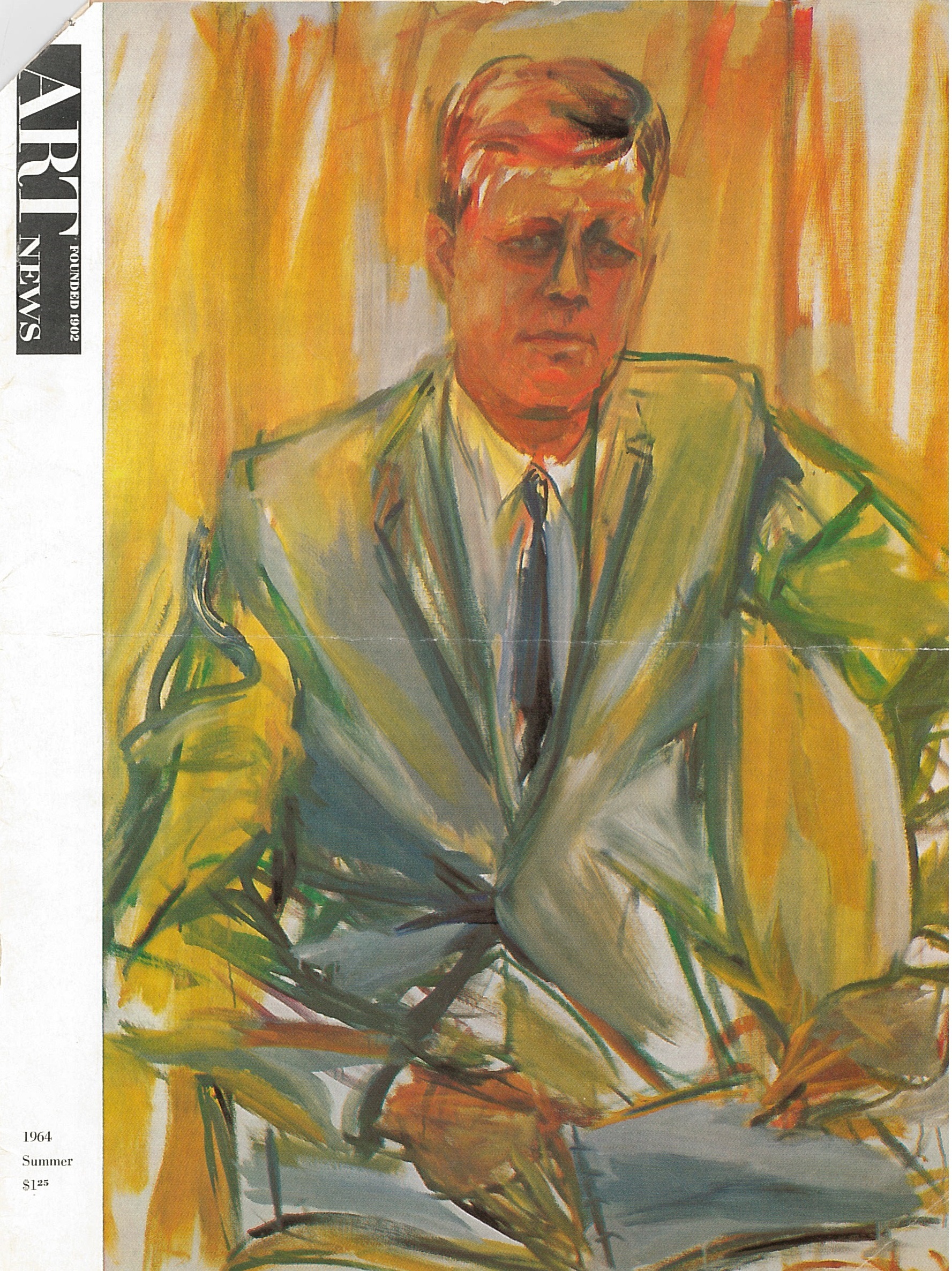

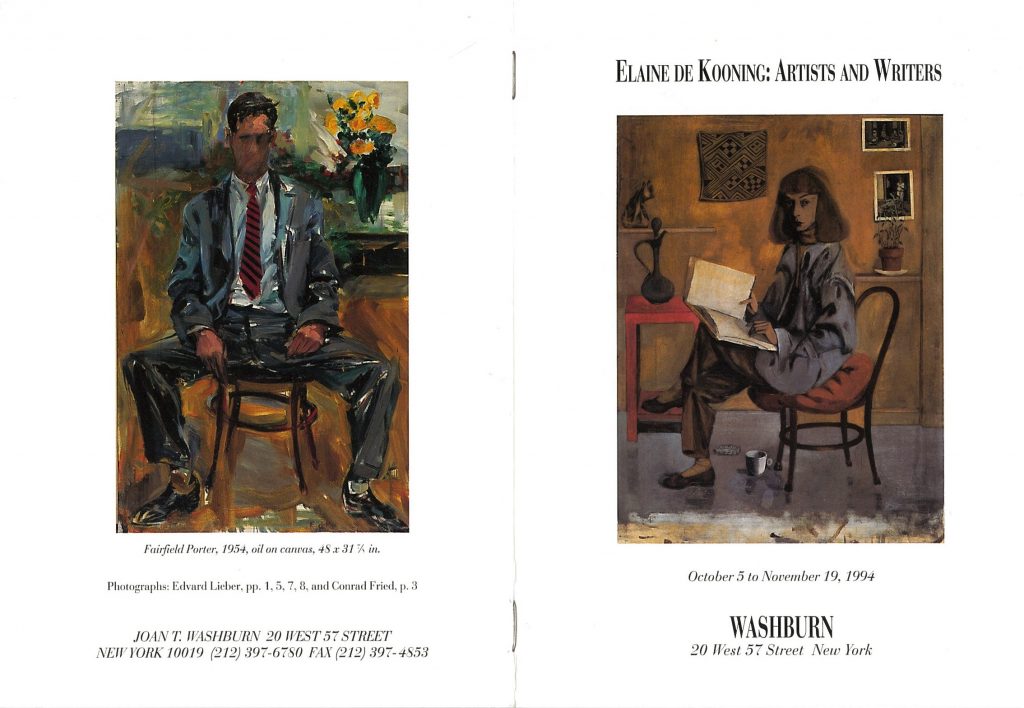

The National Portrait Gallery is currently exhibiting the work of Elaine de Kooning in the show Elaine de Kooning: Portraits, organized by Brandon Brame Fortune, the Portrait Gallery’s chief curator and senior curator of painting and sculpture. Elaine was an active member of the Abstract Expressionists in New York, a group known for a style defined by vivid colors, spontaneity and emotive strokes of thick, layered paint on monumental canvases. She married fellow Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning in 1943. However, Elaine’s work was not solely abstract, in fact, the majority of her work is representational in nature—a style that could be categorized as Figurative Expressionism.

The inescapable question for any college senior is always some variation of “So, graduation is coming up soon, what you plan on doing with your future?” It seems that all other conversation topics must make way to this frightening yet incredibly relevant question.